New research on teaching Māori language in English-medium schools could make a huge impact on how te reo Māori is delivered in New Zealand classrooms. For Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori, Kura Rutherford reflects on the research, and asks just what it will take to bring te reo Māori to life in mainstream schools.

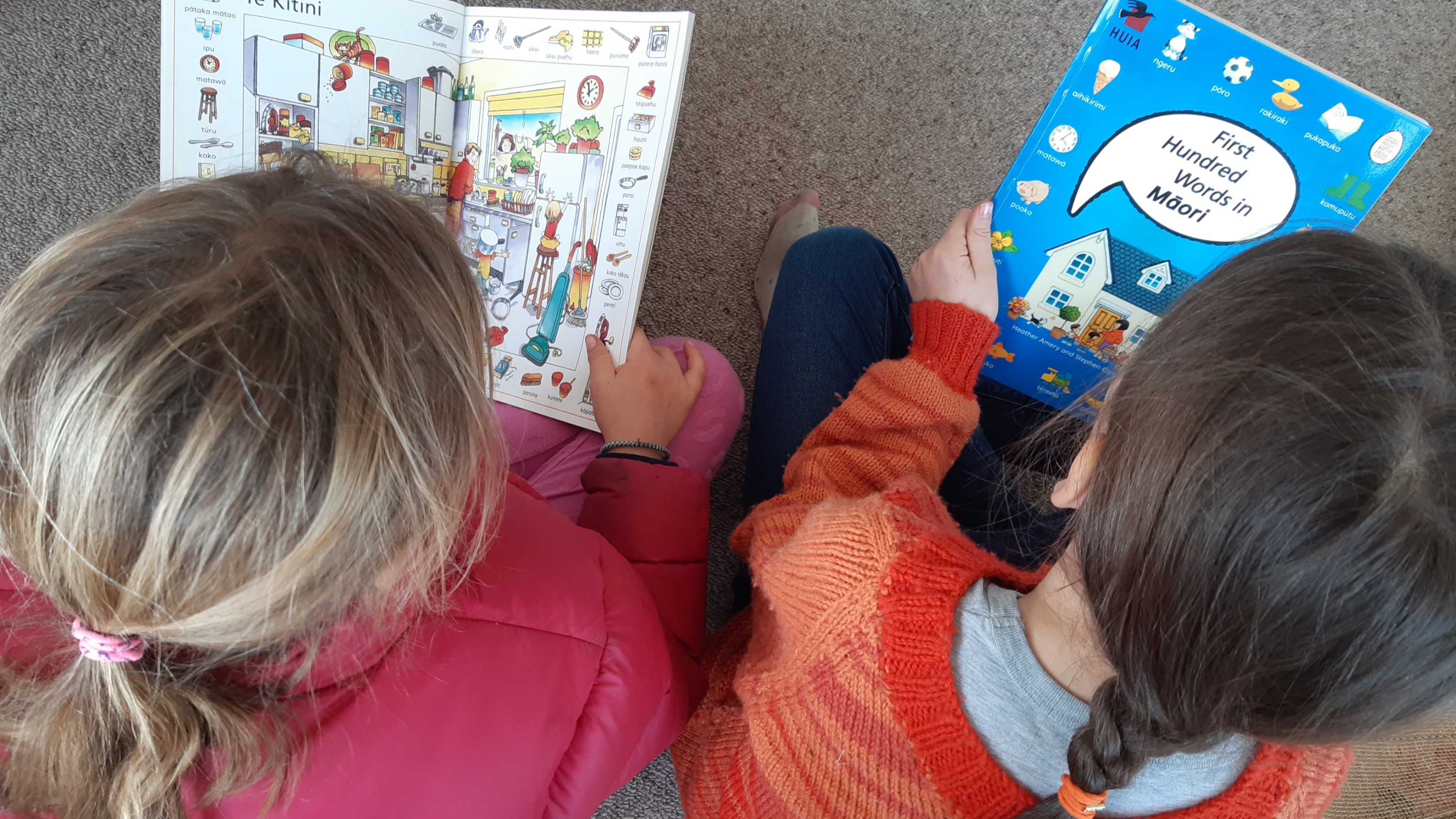

Picture this: a regular school day, kids slipping between te reo Māori and English as they call for a pass on the basketball court, or lying sprawled on the library beanbags reading books in te reo Māori. Children inventing word games in te reo Māori during their poetry lesson. School as a place where Māori language is dynamic and thriving, a part of daily life.

This dream is probably a reality in lots of Kura Kaupapa Māori in Aotearoa, but what about in the majority of our schools – English-medium schools? Are we getting closer to that picture? Is this scenario even possible?

It’s no secret that our education system has a checkered past in terms of Māori language. Up to and during the 1960s children were being actively discouraged from speaking te reo Māori, and work to redress that has been slow.

In some areas we have seen transformation; in the 1970s, vibrant young activists, led by Ngā Tamatoa and the Te Reo Māori Society, marched to parliament to demand change. In the 1980s, the Kohanga Reo movement was established, and then, as pupils were ready to enter formal schooling, Kura Kaupapa Māori. Students from both Kohanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori are now enriching our workforce, and greatly adding to revitalisation efforts..

But where are mainstream schools in this picture? What has changed since the 1970s, the 1980s? Granted, there are some schools that are really striving, but those schools are up against the odds – it’s hard making te reo Māori programmes work without robust policies and funding to support them. To varying degrees, English-medium schools have been flying under the radar leaving the heavy-lifting of revitalisation to Kohanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori alone.

Until now, that is, because last month ground-breaking research was published that focuses exclusively on this area of need.

Whakanuia Te Reo Kia Ora – Evaluation of te reo Māori in English-medium compulsory education, commissioned by Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori and undertaken by Māori language and research consultants, Haemata, provides up-close evaluation of 11 Māori language programmes running in English-medium schools, honing in on what is working well, and in doing so, providing a ‘blueprint’, at both a government and local (that’s us!) level, for how we can implement and transform Māori language learning in schools.

The research forces us to ask what it means for a language to ‘thrive’, and what ingredients are needed to bring te reo Māori programmes to fruition in all schools, so that we can redress past injustices, honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and truly give te reo Māori the status it deserves. It’s impossible to do full justice to the findings of the report here, but some of the essential ingredients reported in the research were:

Strong whānau connections – we’ve heard it before, but it’s where everything starts. Whakawhanaungatanga, building connections – between school and home, between school and local iwi. This might mean having an open-door policy at school, or inviting whānau in to join the morning karakia, to join language classes or to share their expertise.

Supportive strong leadership – that is, a leader who is committed to the learning, support and valuing of te reo Māori in their school, is very clear on their obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, is inspiring their team and community with a vision that sees te reo Māori as alive and thriving in their school…and has prioritised funding to make their vision a reality!

A clear picture of why the work is needed – that catch phrase about “knowing your why” is so relevant in this work. There are so many benefits to learning more than one language, and many more to learning Māori language in particular; be it cultural, social, cognitive, or personal, and not least because te reo Māori is a taonga unique to our country, and a vital part of our identity as New Zealanders.

A programme that is the ‘best fit’ for its community – there are a myriad of innovative ways to increase Māori language in a school, it needs to serve its community. It might be creating a specialist te reo Māori teacher role, employing a professional facilitator for a time to help upskill staff, developing a whānau led language strategy, or increasing integrated and paralleled learning – the report shows that there are ways forward.

People making plans – that is, staff, whānau, local iwi and students, mapping the way; planning for success and for the challenges. The report promotes the value of ‘backward mapping’; firstly identifying the long-term goal or vision, then working backwards to develop the steps needed to meet that goal. Starting with a big picture vision for the future is essential, and knowing that challenges are inevitable means some of these can be planned for before they happen.

Putting language first – the research shows that in many schools language learning takes a back seat to cultural elements such as waiata and kapa haka. So it’s important to make language the first priority if the goal is growing language proficiency. This means creating a scaffolded programme that increases language complexity each year, includes grammar, and is delivered in a way that is interesting, suitably challenging, and relevant to students.

Maybe these ingredients are already evident in some of our schools. But if not, what needs to change?

Is there one step you can take right now to increase te reo Māori in your child’s school life? Is there something you can do to lobby for funding and policy change?

These are questions for all of us, as a country, and personally. Imagine that school of the future; the shelves of the whare pukapuka jam-packed with colourful chapter books written in te reo Māori, children counting their skipping in te reo, or writing a play – school as a place where Māori language is flourishing.

Imagine that school of the future; the shelves of the whare pukapuka jam-packed with colourful chapter books written in te reo Māori, children counting their skipping in te reo, or writing a play – school as a place where Māori language is flourishing.

The call is clear, if te reo Māori is to survive and – ultimately – thrive, we all need to be doing the mahi, at a governmental level, at a local level. If it’s our children who will carry our indigenous language into the next era, then some attention needs to go to mainstream schools now. This research gives us all valuable new tools to help see that happen.

Many thanks to Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori and Haemata for giving me their blessing to write about the research report Whakanuia te Reo – Evaluation of te reo Māori in English-medium compulsory education. All of the ‘essential ingredients’ described in this article are my direct personal interpretation of the findings of the report or are taken from the 10 Snapshots provided by the researchers.

As we close our celebration of Te Wiki o te Reo Māori 2019, please also revisit Nadine Anne Hura’s advice during Te Wiki 2017 in Te Reo Māori in Schools: 10 Things You Can Do.

Kura Rutherford

Kura Rutherford (Te Rārawa, Ngāpuhi) is a school librarian, writer and editor, who lives in Tāmaki Makaurau. She grew up in Hokianga and Grey Lynn, before moving to Hawke’s Bay for 20 years with her husband, Dominic, to bring up their three daughters. She worked for 10 years in public libraries in customer service and community roles before becoming the sole charge school librarian at Taikura Rudolf Steiner School in Hastings. Now having returned to Tāmaki with her family, she works in the same role at Michael Park School in Ellerslie. She has been connected to Steiner education since she was 23 when she and her husband worked for a year at Hōhepa Farm in Hawke’s Bay, and all three daughters have attended Steiner schools. Kura’s writing focus is on health, education and literature, and she has written for The Sapling, Good magazine, EBSCO databases, Magpies magazine, and craft magazine Extracurricular. She has a special interest in supporting organisations in their te reo Māori strategic planning and development aspirations.