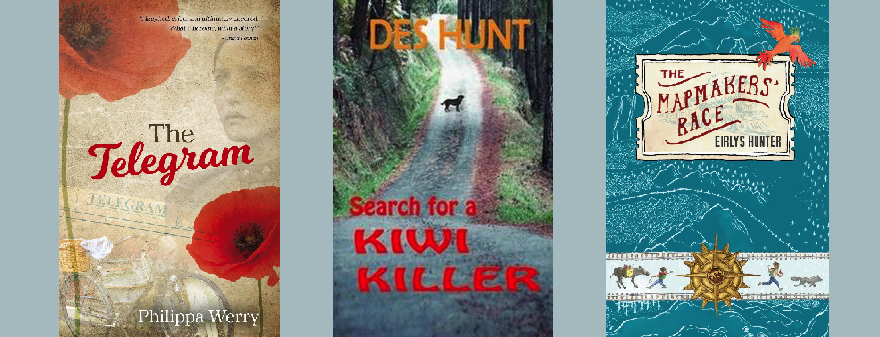

As the next instalment in our coverage of this year’s NZ Book Awards for Children and Young Adults, we asked the five finalists of the Wright Family Foundation Esther Glen Award for Junior Fiction to interview each other. Here’s Philippa Werry, Des Hunt, Eirlys Hunter, Bren MacDibble and Steph Matuku talking the genesis of their ideas, planning, and childhood influence.

Philippa Werry: Can you remember the moment when the germ of the idea for this book came to you?

Des Hunt: The idea of writing a story about a dog killing lots of kiwi had been in my mind from 1987 when a single stray dog in Northland killed between 400 and 500 kiwi in Waitangi Forest. The idea remained in the back of my mind until September 2016 when I was invited to the NZ Literacy Association Conference in Kerikeri. I arrived a day early and spent some time cruising the roads surrounding the town. Driving along Inlet Road I encountered numerous signs about kiwi including one in particular that was painted on the road near the entrance to Waitangi Forest. When I saw that sign, I decided a kiwi story would be my next writing project.

Eirlys Hunter: I can! I heard Kate de Goldi give a keynote speech somewhere, in which she talked about chewing your own bone – interrogating your own obsessions as a starting point for a story. So I made a list of childhood and current obsessions, top of which was maps. And once I started brooding about maps the rest just followed.

Bren MacDibble: I think it was at a Continuum Conference in Melbourne maybe five years ago? Where a food scientist came along to deliver a presentation on future food production. That was an amazing idea for a science fiction convention, thank you Continuum. I chatted with Cat Sparks and Jason Nahrung afterwards about how dreadful a grass famine would be. The book Dark Emu came along. And I’d always wanted to write a book about kids on a dog sled, a kind of Mad Max desert dog sled thing, so a few germs all mushed together in my brain there.

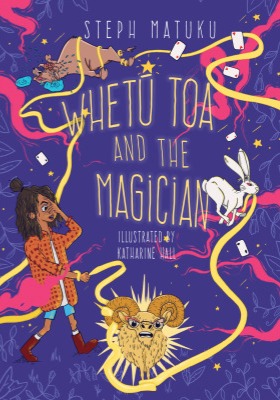

Steph Matuku: I always knew I wanted to write the kind of children’s book I would have wanted to read when I was little – one with animals, lots of magic and a Māori girl who looked like me. So I guess the idea started a long, long time ago, but the urgency to write it only came about last year when I was twiddling my thumbs looking for something to do.

Eirlys Hunter: How much of the story have you worked out before you begin to write a novel?

Des Hunt: I always have the structure and location for the climax planned before I begin writing. There will also be jottings about the action that leads up to the final scenes. I spend several weeks on planning, but there always comes a time when my impatience to write takes over. I’m also aware that stories can develop a mind of their own and drag you away from any overly-planned path.

Philippa Werry: I am not a detailed planner and I like surprising myself with what happens during the course of writing a book. But having said that, The Telegram is a historical book and closely tied to actual events of World War One, the Armistice and the influenza epidemic, so the ‘big events’ were already set for me; I just had to figure out a way to weave my story and my characters into and around them.

Bren MacDibble: Not much at all. Mostly a main character and a general idea. I write to figure it out, get to know the character and tell myself a story. Then I go back and rearrange things, layer up other ideas. I’m not a planner. I work on the theory that I already know the shape of a story. If I have any good ideas or questions that arise I jot them down at the end of the manuscript and go back to them daily.

Steph Matuku: I plan very thoroughly. I work out my beginning, middle and end, and then figure out how many words I need to get there. I write up my characters’ backstory, and research the world they’re in. Then I start writing and nothing happens the way I want it and the plan goes completely out the window. I always end up feeling my way along, chapter by chapter. And when I get to the end of the story, I look at the original plan and tear it into tiny shreds.

Steph Matuku: How do you keep yourself sitting in your chair and writing without getting distracted?

Des Hunt: Distraction usually becomes a problem when my writing is not flowing, often because I’m unsure of where it is heading. When that happens I grab the dog lead and take Puku, our beagle, for a walk along Matarangi Beach. I find the sounds of surf soothing, and at 3.5 kilometres the beach is long enough to sort out most problems.

Eirlys Hunter: Short answer? I don’t. The Mapmakers’ Race took years to write. I chipped away at it between all the other happy distractions of life. Writing the first draft of a novel is so hard I constantly seek out urgent alternative occupations – like checking if anything exciting has appeared in the fridge, or sorting the odd sock box. But once the story is in place, I find it much easier to put in the hours. I love the tightening process: pruning away unnecessary sentences and words, and making the plot appear seamless.

Bren MacDibble: Sometimes I get really distracted! Mostly, I fall in love so deeply with my story, I don’t care what the world is doing around me. Sometimes I’ll lift my head and pretend I’m in this world but all the time my head is in my current work. I know I’m doing it right if I’m wanting to be in that world more than this one. So I guess I try to go to the ‘place’ in my head where the story rules. I don’t have any tips about rearranging my physical world to make it easier except maybe a bowl of peanuts. Always nice to crunch on peanuts while you work.

Philippa Werry: Actually I do believe a little bit in distraction. I do a lot of work in my head when I’m walking up and down the Wellington hills, and even taking a break to hang out the washing can feel like it’s giving my brain a chance to catch up and ponder and wrestle with tricky writing problems. But I think trying to write with small children around was the best training for learning how to concentrate on and make the most of any available writing time. I clearly remember trying to write by the side of the pool during their half-hour swimming lessons.

Des Hunt: Which narrative mode and tense did you use in your story and why did you choose each of those?

Eirlys Hunter: I fiddled around for ages with this story. It started in the first person (Joe), but then I realised that I’d need to see events from other points of view. So I settled for the third person, past tense, with two point-of-view characters (Sal and Joe) whose chapters (almost) alternate. The narrative is also punctuated by stream-of-consciousness passages from their mute artist sister Francie, which are signalled by a small feather. These are in the present tense and the first person, but there is no ‘I’ in her thoughts.

Philippa Werry: The Telegram is written in the first person because I wanted the reader to be right beside Beatrice every step of the way and standing beside her as she knocked on doors with what could be good news or terrible news in her hand. It’s written in past tense because somehow that makes more sense to me for writing historical fiction. We know the events (both fictional and real) happened a long time ago so it seems more logical to be in the past tense, or maybe it’s more that it would be confusing if it was in the present tense. I’m confusing myself now, thinking about it. Past tense just made more sense!

Bren MacDibble: First person, present tense. I’m trying to draw the reader into a deeply intensive character experience. I don’t want to distance the reader with the abstracts of writing or a story from the past that happened to someone else. I want the reader to feel the story is here now, unfolding around them, happening to them. I also write physically, immediately, and make sure the language the character uses is appropriate to their experience of life. Anything formal is too distancing, I even change sentence construction to flow in the colourful way we all corrupt language when we speak rather than write. I hope in that way my character will connect with the reader.

Steph Matuku: I wrote Whetū Toa and the Magician in the third person, past tense, from Whetū’s point of view. I like to write in third. It means I know exactly what Whetū is doing and feeling at all times and I can also talk behind her back if I want to. I think it’s just habit really, writing in third person, past tense. It’s familiar and comforting.

Bren MacDibble: Is there any scene in your shortlisted book that directly relates to an experience in your childhood or that of a close friend?

Des Hunt: In chapter three my main character, 12-year-old Tom, encounters his neighbour Dave, a man who lost his arm in a forestry accident. This causes Tom lots of embarrassment because he can’t take his eyes off the bare stump that waggles around just below Dave’s shoulder. I had a similar experience at the age of 12 when I was spending the summer holidays on an uncle’s farm. During haymaking farmers came from neighbouring farms to help out, and one of these had a stump instead of an arm. He and I worked together stacking bales of hay, he with his single arm at one end, me with my skinny, weak ones at the other. I found it almost impossible to not stare at the stump.

Eirlys Hunter: Not from my childhood, but in my book the children come upon a waterfall hundreds of metres high, and discover they can scramble behind it, right through to the other side. This was something I did with my children at the Sutherland Falls on the Milford Track, many years ago. It was the most exhilarating thing I’ve ever done.

Philippa Werry: I find it very poignant how Beatrice and her best friend Beth drop out of each other’s lives (that’s not really a spoiler, because it happens in the first chapter). It makes me remember how easily that could happen in the days before social media. I had a close friend at school who went overseas when we were about ten, and we wrote letters for a while and met up again once, but gradually lost touch. I still think about her sometimes and wonder how she is. Thanks for the good question which has made me realise a connection I hadn’t seen before.

Steph Matuku: Not really – I wish we had dishes that could wash themselves! But I do think that the underlying themes of the book we can all relate to, especially to that of being chucked in the deep end and forced to swim or sink like a stone. Whetū is put into unusual situations that she has to deal with, and even though she’s nervous and has no idea what she’s doing, she gives it a go anyway.