Home Child, based on child migrant Pat Brown’s early life, is such a major change of pace, a poignant, heart-wrenching story by a writer so well known for her hugely successful funny rhyming books like I Need a New Bum, Melinda Szymanik wanted to know where it had sprung from.

I’d received Dawn McMillan’s latest picture book, Home Child (Oratia, 2019), in the post a few weeks previously, and I was keen to have a chat with her about it. This book, based on child migrant Pat Brown’s early life, is such a major change of pace, a poignant, heart-wrenching story by a writer so well known for her hugely successful funny rhyming books like I Need a New Bum, and I wanted to know where it had sprung from. And how Dawn juggled those very different styles.

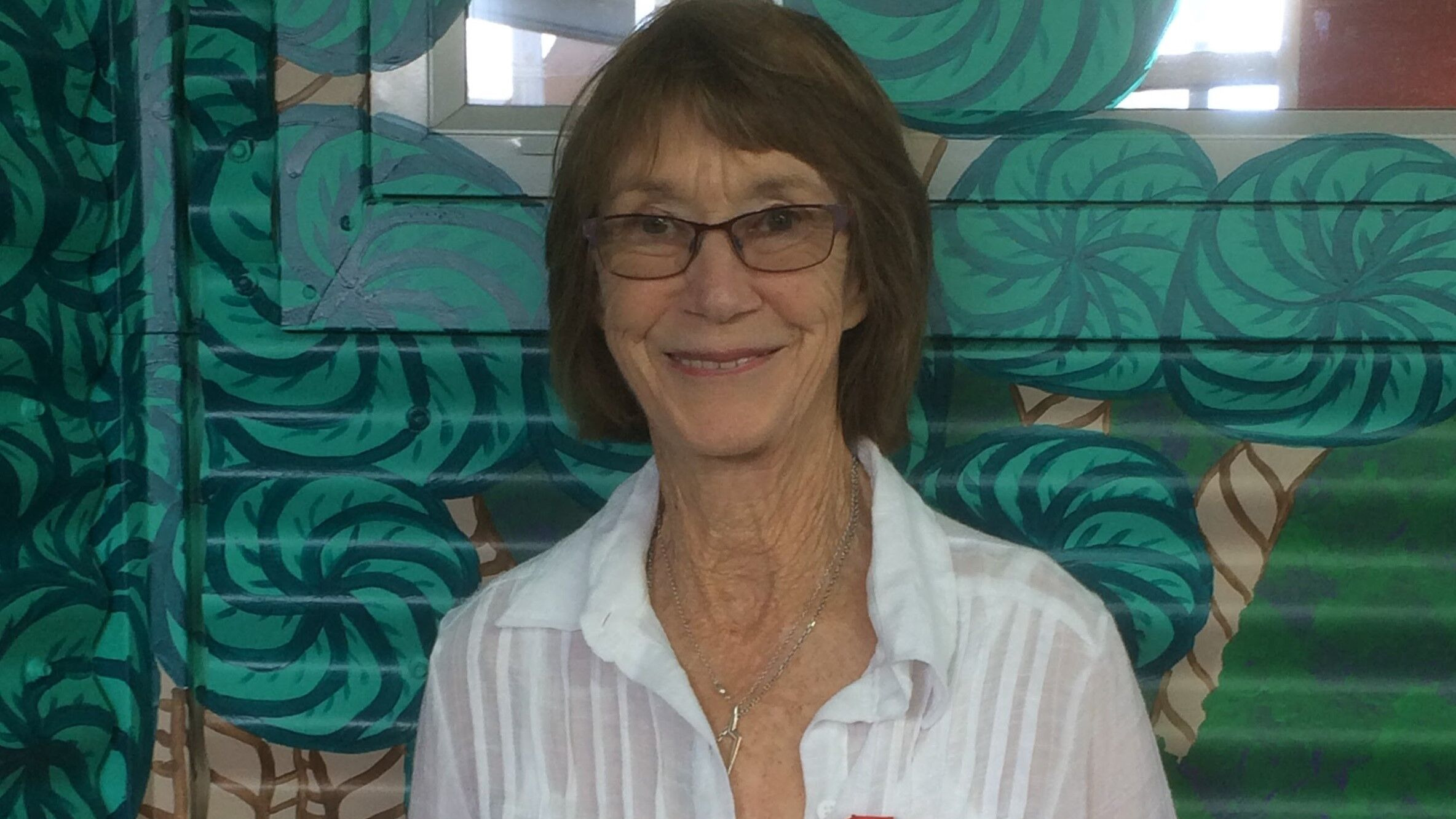

Dawn lives in Waiomu, 14 kilometres north of Thames, with her husband Derek. They’ve been there nearly twenty-five years, in their little white cottage across the road from the local café, which, in a wonderful display of community support, sell heaps of Dawn’s books. I live in Auckland, so I video messaged her and got a glimpse, not just into her writing studio, but into her life, and even into the two sides of her writing brain.

I video messaged her and got a glimpse, not just into her writing studio, but into her life, and even into the two sides of her writing brain.

A third generation New Zealander, her earliest years were spent in Te Kuiti, until, for a change of climate for the sake of the then seven year old Dawn’s health, the family moved north to Okaihau, near the Bay of Islands. Dawn wrote poetry and little stories as a child, but gave this up when she went off to high school. She trained as a primary teacher, taught, and had a family, and didn’t pick up writing again until the move to Waiomu.

‘All of a sudden I wanted to write’ she says. Sea Secrets was her first book published in 1998, ‘so I’ve been going twenty-one years.’

While Dawn’s preference has always been to write picture books, she’s also written many school readers over the years. ‘I’ve done lots of those – about 220 I think … they’re sort of the bread and butter really. That’s what lets me go to the supermarket.’ So, literally the bread and butter.

Close to the beach, a park, a stream and the bush, Dawn finds her environment a major source of inspiration and feels this is what got her writing again. ‘This place has got some amazing energy, this coastline. I tell the kids that the story ideas are just leaping out all over the place. And it feels like that sometimes.’ But this isn’t what sparked the idea for Home Child, and I was a little surprised to find that I had played a part in bringing Dawn and the story of the British Migrant Scheme together.

‘This place has got some amazing energy, this coastline. I tell the kids that the story ideas are just leaping out all over the place. And it feels like that sometimes.’

She’d been wanting to write a longer book, ‘an intermediate novel,’ and had fixed on the story of the Polish children sent to New Zealand in 1944, but discovered when googling the topic that I was already working on a book about this (Dear reader, I regret to inform you that this is still a work in progress). But Dawn was still fascinated by the topic in general and kept looking for possible ideas to write on. She stumbled across the British Migrant Scheme and found an article from a Nelson newspaper about Pat Brown, one of the children brought to New Zealand under the scheme, who’d returned to England to receive an apology from British PM Gordon Brown. She rang every Brown in the Nelson directory and spoke with the journalist who’d interviewed Pat but had no luck tracking her down till someone mentioned Pat’s sister during a conversation.

Dawn wrote to Pat care of her sister, and her dogged persistence paid off when one night she had a phone call from Pat herself. ‘[Pat] said, “Oh, I’ve been wanting someone to tell my story for so long.” She sent me all her treasures: photographs, the original ticket to the Captain’s dinner on the boat over, the Christmas menu. She sent me CD recordings of her talking with Mark Sainsbury … And so I had all this material, and her personal notes. That’s how it started. And of course I just built on it from my research as well, checking everything out with her as I went.’

I loved the beginning of the book, as it opens with such an important reminder to us all:

‘Our family has a story … Gran’s story. I ask her to tell it to me again.’

Every family has their own stories, and knowing the past is so important to understanding our present, both personally and on a wider social scale. This opening line invites every reader to do the same. And even though ‘Gran’ is reluctant:

‘Gran says, ‘I’m not sure it matters anymore.’

Every family has their own stories, and knowing the past is so important to understanding our present, both personally and on a wider social scale.

it is up to us to acknowledge that all lives matter, and all our stories are important. And Dawn gives us this with the granddaughter saying:

‘…it does matter’

and ‘The world needs your story.’

Throughout the book Dawn displays her poetic roots with some wonderful language which lifts some of the sadder elements of the story. Sentences like, ‘I held my breath as the ship squeezed between the walls of the locks,’ while across the page you’ve got, ‘Across the pacific where the trade winds buckled the sea’. It was unsurprising to find Dawn still writes poetry.

Throughout the book Dawn displays her poetic roots with some wonderful language which lifts some of the sadder elements of the story.

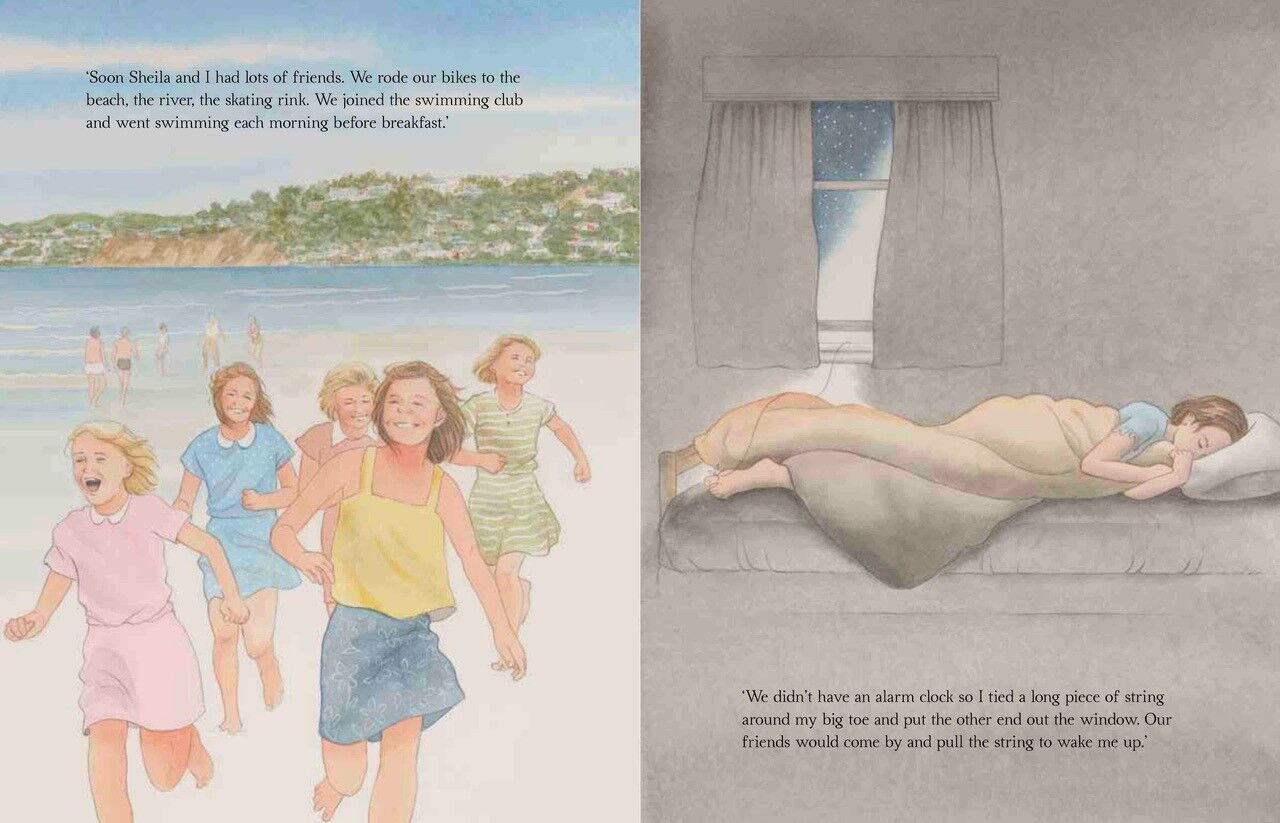

Throughout the book she was keen to give balance to Pat’s story. ‘I didn’t want it to be all doom and gloom. I wanted it to reflect her life. She’s a very warm, loving, positive person and I wanted that to come through … although she was interviewed relatively recently on television, and the hurt is still there … I wanted the hurt to be in the story, but I didn’t want it to be morbid or to bring the reader down. I wanted it to inspire too, to let the reader feel hopeful.’

To this end the book shows that, although Pat started out in poverty, albeit in a loving family environment with her Dad and siblings, she ended up making a good life for herself in New Zealand. And the trip out on the ship was an enjoyable experience with music and parties for the young migrants. ‘She said it was the best time of her life, at that stage anyway. She was totally stoked with that boat trip … I mean they had sheets for heaven’s sake. You know, she’d never had sheets.’

‘She said it was the best time of her life, at that stage anyway. She was totally stoked with that boat trip … I mean they had sheets for heaven’s sake. You know, she’d never had sheets.’

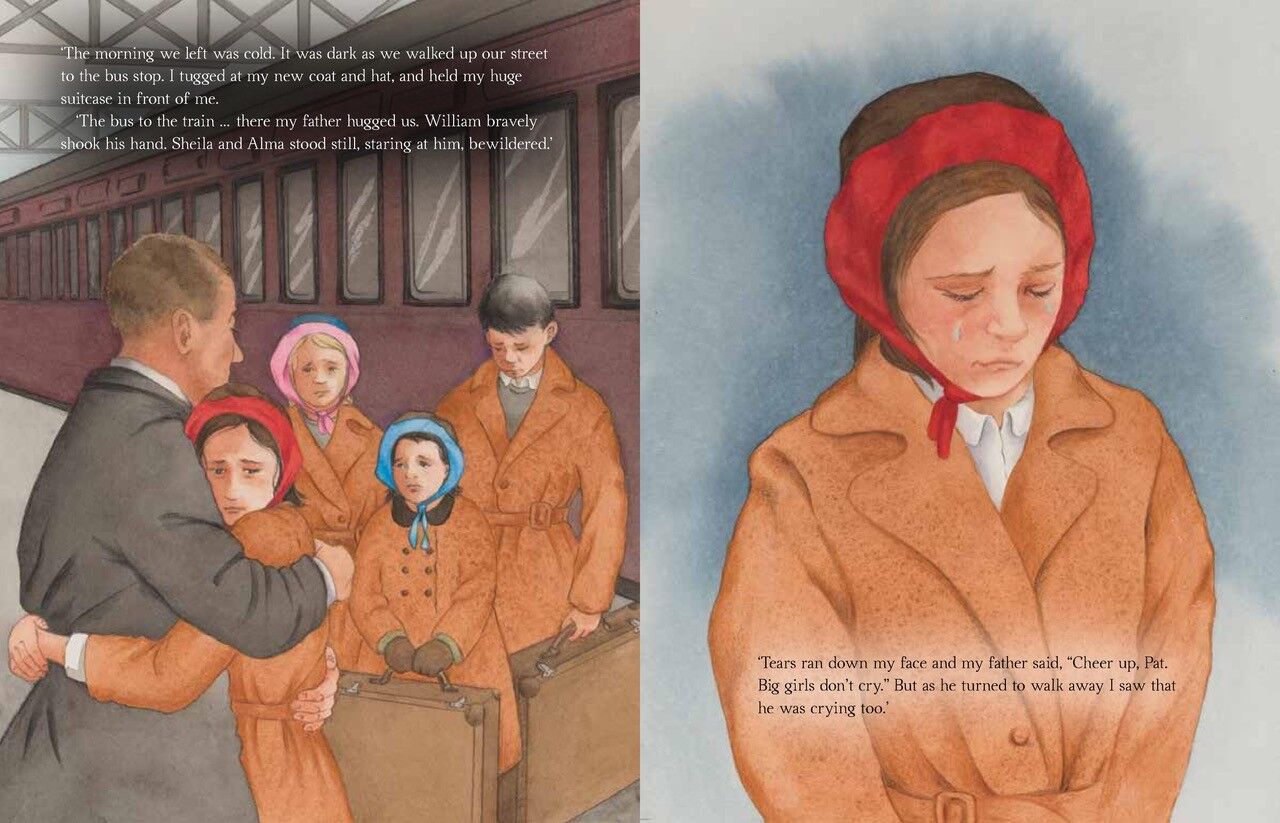

Ultimately though, the British Migrant Scheme was about providing ‘human cargo to populate the colonies’ and families were often torn apart with little thought to the long term consequences. Dawn thought it likely that the Dad didn’t have, ‘… any idea the children weren’t coming back and of course they didn’t have any idea they weren’t coming back either.’

I’d also felt, on reading the book that the children didn’t even really know why the were being sent away and Dawn agreed that that was how she’d seen it. ‘… the father didn’t understand either. He thought he was doing the right thing … Pat was only eleven when she left, and I’m combining her feelings with my interpretation and obviously its not too far off the mark, is it? If she’s so happy with the story. I sort of felt as if he was conned, really. The officials arrived with papers and said, ‘Your kids will be better off, they’ll get a better life in New Zealand,’ and he thought he was doing the right thing.

Not all of the children would have ended up in good homes either. ‘I think there were a few lucky ones. I touch on it briefly in Home Child when I say they were looking for love. I think they had a difficult time, even in a good home.’ The book certainly has that undercurrent of trauma and sadness, but it doesn’t overwhelm the story, and there is some unexpected joys in store for Pat at the conclusion.

This story was a two year labour of love for Dawn, who, when the first draft was completed, met with Pat and her husband in Nelson. She read it to them and said, ‘I want to see if it’s okay for you.’ [Pat] cried, and he sat there and said, ‘This is just how she’s told it to me all these years.’ It was a wonderful moment for Dawn, and just the endorsement she needed to finish the book.

As an author, when working with real life experiences it’s a huge responsibility to tell these stories without diminishing them in any way. I felt the weight of this when working on my Dad’s story (A Winter’s Day in 1939) and it’s very clear that Dawn felt the same responsibility with Pat’s. She’s discovered so few people in New Zealand know about the British Migrant Scheme and of the children that were uprooted from their homes, their families, and their culture and brought to a strange place across the other side of the world. And their experiences echo those of today’s refugees, which will resonate with young readers.

In the end, Dawn’s goal was to ‘tell Pat’s story. In a way that Pat wanted it told really. Pat needed it to be told.’ The book achieves this beautifully, and one of the loveliest outcomes has been the friendship that has developed between the two women. They text, and email each other. Dawn says, ‘when we met, it was as if we had known each other for hundreds of years … I feel as if I was meant to meet her, and connect with her personally as well as her story.’

In the end, Dawn’s goal was to ‘tell Pat’s story. In a way that Pat wanted it told really. Pat needed it to be told.’

Home Child is a compelling, and serious read, in great contrast to the more frequent humourous books that Dawn produces. I know she’s written other books on similarly thoughtful topics but I wondered at the significant difference between the two styles, or more to the point, the two sides of Dawn McMillan, especially as she is so good at both. Do they require different processes? And did she have to be in a different head space to write one or the other?

‘My husband, and my family would say that they’re extremes … I don’t consciously make a choice. I don’t consciously switch between. I don’t even know what I’m going to write until it starts. Of course the more serious ones, you’ve got to do the research. I get the feeling about it first and then I develop it, whereas the silly ones just sort of bounce into my head. But I don’t sit here and think I’m going to write a serious one this week, or I’m going to write a silly one this week.

Of course the more serious ones, you’ve got to do the research. I get the feeling about it first and then I develop it, whereas the silly ones just sort of bounce into my head.

I was interested to hear how similar our experiences and processes are. An idea pops into our heads and we just follow it and see where it goes. ‘It doesn’t rely on my mood,’ Dawn said and I thought, ‘well yes, that’s true.’ However, while the shower seems to be a place that conjures ideas and plot solutions for me, for Dawn, some of her ‘silly’ stories start in the car or when she’s walking. ‘It’s the rhythm. The rhythm triggers some of my silly things. The more serious ones, well, Colour the Stars was set in a place that I walk to, up the creek. And I sat there and it just felt like these two boys came to tell me the story. So that was a little bit spooky really.

‘The Harmonica is another one of my serious ones that I really love. I’m not sure what triggered that. It might have had something to do with my uncle Frank, who was a prisoner of war. That might have been ticking away in my mind.’

Were funny stories easier to write? Again we had things in common. Some stories almost write themselves and others need to gestate and percolate. As has happened to me, sometimes Dawn gets, ‘a couple of lines of something, and I can’t do anything with it. Nothing will come. Doesn’t matter how much I try to craft it or anything, it won’t happen. Like Mr Spears and His Hairy Ears – I had the first couple of lines of that for about nearly two years before the rest of the story came in. I knew what it was going to be about but I had no idea what was going to happen, and then … all of a sudden it just came in.’

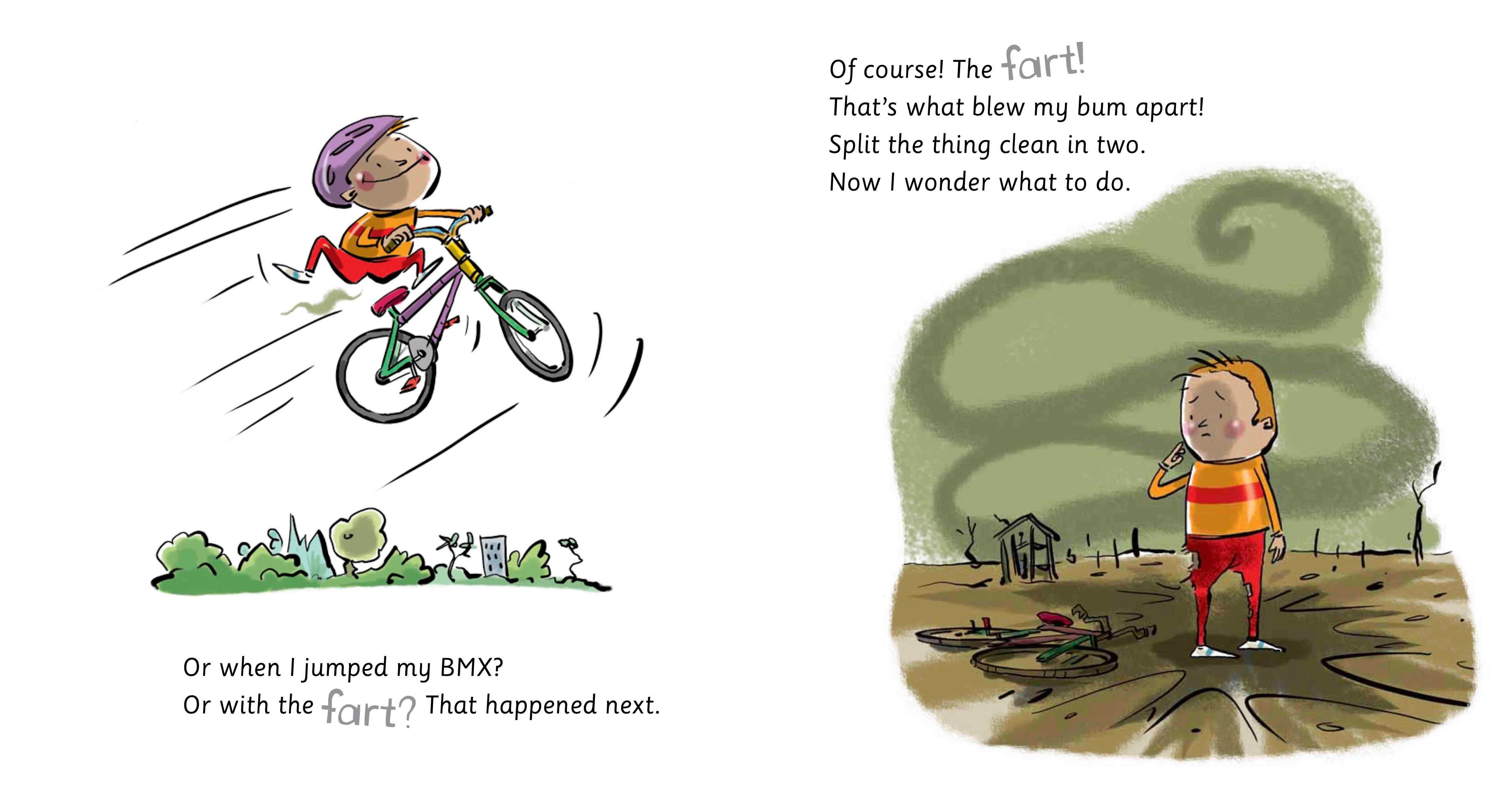

But those silly ones can come in quite quickly. A couple of hours and I’ll have the basic thing just pounding in my head. They go over and over. I Need a New Bum started when I was on my way over to see my uncle Frank and it started about a hundred metres from home, rabbitting on all the way to Rotorua. And it self-corrected! It was really interesting. I wish I’d been able to take a video of what was happening in my brain. It self-corrected. I got to Rotorua and I thought I have to stop and write this down otherwise I might forget it.’

We’ve all regretted the times we didn’t stop to jot something down. I found myself nodding vigorously as Dawn talked about her process. But it was the story Dawn told at the end of our chat that showed why she is such a master of the humorous tale.

She said, ‘I think I can blame my father for starting all of this because when I was a child he used to tell me little snippets of this story about dogs smelling bottoms, but he wouldn’t tell me the whole story because he said he’d forgotten.’ It turned out it was more likely he never told her the whole thing because it would have been a wee bit naughty for his then young daughter.

But when her Dad was in hospital towards the end of his life, Dawn decided to write the story and fill in the gaps herself. She read it to him and he loved it. Reed was her publisher then, and Vicki Marsdon her editor. Dawn,’ wrote to her and … said ‘Here’s a story I wrote for Dad. I know you won’t publish it … its just a bit of fun,’ because they’d said ‘no talking animals, and no rhyme,’ because that was how it was. Well, in three days it was contracted.

‘So I think we can blame Dad for my silly stuff. We used to drive my mother mad. Poor Mum. I realise now that she must have felt left out. I didn’t think about it at the time. We used to drive her mad because Dad and I used to speak in rhyme at the table all the time, and talk a lot of nonsense. So I think that’s the root of all my silly stuff.’

What a great training ground that must have been for the young writer-to-be. Dawn was inclined to, ‘blame Dad. Its all his fault. Bless him,’ But we shouldn’t be blaming him, we should be thanking him. Between the funny, rhyming, nonsensical Dad and the patient, more serious Mum, we have been given the amazing Dawn McMillan who writes so wonderfully at both ends of the spectrum.

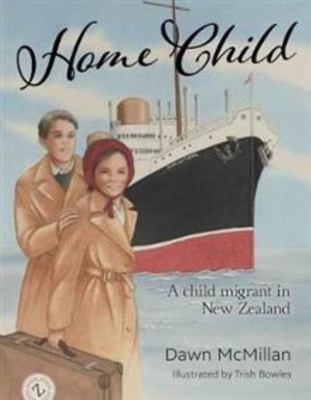

home child: A child migrant in new zealand

By Dawn McMillan

Illustrated by Trish Bowles

Published by Oratia Media

RRP: $27.99

Melinda Szymanik

Melinda Szymanik is an award-winning author of picture books, short stories and novels for children and young adults. She also writes poetry for adults and children, and regularly teaches creative writing. Recent titles include Lucy and the Dark (Puffin [Penguin RH], 2023) and Sun Shower (Scholastic, 2023).