Achieving international rights is the ultimate dream for any writer. However, in New Zealand, achieving that dream is almost impossible. Author Melinda Szymanik looks at why international rights are so elusive in Aotearoa, and what opportunities our authors miss out on.

When my first children’s book was published, way back in 2006, I was a bit shocked to discover that international rights sales were not automatic. International sales were the holy grail, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, and everyone got them, right? I naïvely thought my first book would sell around the world and that that was the norm. My publisher was part of a large international publishing family—wouldn’t that all but guarantee it?

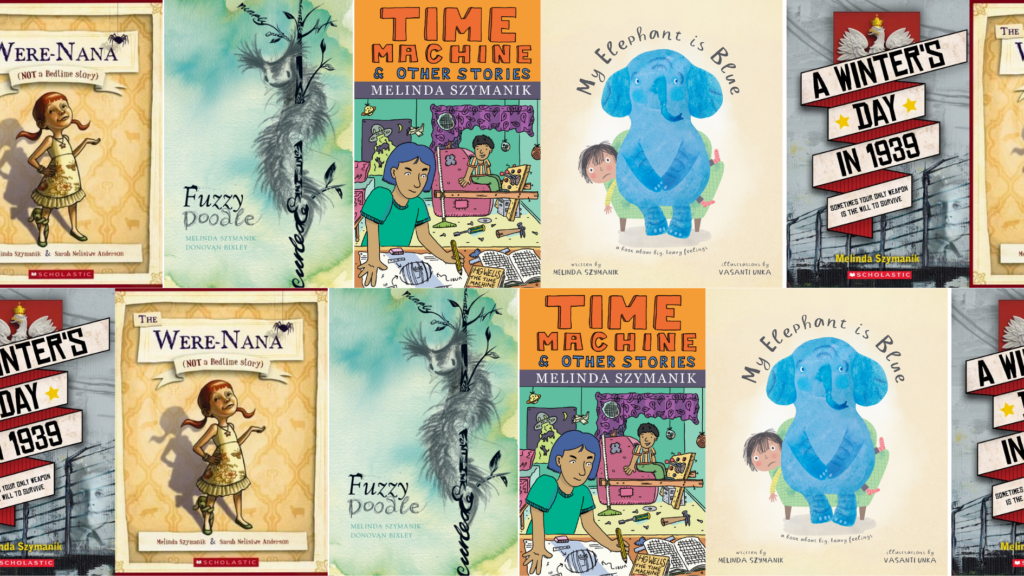

Maybe the content was too local or the book just not good enough, but when my first novel and second picture book came out a few years later (the former set partly in Europe, the latter referencing Little Red Riding Hood and with a ‘could be set anywhere’ vibe) I thought, ‘surely now.’ When the picture book was shortlisted for the NZ Post Book Awards and won Children’s Choice I thought I would definitely be in! A modest quantity of the picture book was shipped to Australia and that was it. What was I doing wrong?

I naïvely thought my first book would sell around the world and that that was the norm. My publisher was part of a large international publishing family—wouldn’t that all but guarantee it?

Since then, most of my subsequent books have been simultaneously released in the Australian market, and a couple distributed into other more distant territories. One book sold into China in a complex bundle arrangement. When book number eleven came along I thought this one would make it with its universal concepts, its stunning illustrations, and its thoughtful production. It got picked up across Asia and I was thrilled—but results were extremely modest and disappointment set in.

A couple of my more recent titles have fared better including My Elephant is Blue (Puffin, 2021), which has sold into six other territories with multiple translations. I feel enormously lucky and relieved, and am watching and waiting to see how the experience pans out. Will the book sell well in those other countries? Will it make an appreciable contribution to my bottom line? Out of 17 books I’ve had published so far, four have sold into another territory, and two have been distributed outside Australasia. That’s a 35% strike rate. Is that normal? I know of other local children’s authors and illustrators who have had overseas rights sales. But as often as I’ve heard good news, I’ve also been told about how deals haven’t happened. I got to wondering—was my experience better, worse, or just par for the course with other Aotearoa New Zealand children’s writers? I wondered what your average Kiwi children’s book creator should expect. Are we doing well down here or not? What books get the nod? Are there ways to improve our chances of international exposure and success? I talked to fellow writers, publishers and agents. Facts and figures were hard to come by and folk weren’t keen to talk on the record.

I got to wondering—was my experience better, worse, or just par for the course with other Aotearoa New Zealand children’s writers?

Is a presence at international book fairs the ticket? Aotearoa New Zealand is a long way from Bologna, London, and Frankfurt, and it is an expensive business to attend. Many local publishers don’t usually go themselves (with some exceptions), instead having arrangements to have their books represented by affiliates or proxies. It is an understandable approach in view of the big costs required every year, and rights sales are made for local books, but would our sales improve if we had a bigger presence than we have now, providing local passion behind the sales pitches, and a sole focus on New Zealand titles?

What else might stand in our way? A rhyming book will pose difficulties for translators. And quintessentially Kiwi books—naming local flora, fauna and landmarks, using local idiom and colloquialisms—may face obstacles outside Aotearoa. But this cultural specificity hasn’t stopped books from other countries coming here. I grew up on a diet of British, European and American children’s books. So much so that as an adult I have identified with British culture, history and geography. I know all about foxes and ravens, London and Cornwall, King Arthur, yew trees, hawthorn hedges, smugglers, and Henry the Eighth’s wives. I think we have benefited enormously from reading about other countries, other lives, and people different to us. You’d think other folk might want to read about us. As an excuse, this feels spurious. Yet early in my writing career, like many other authors here, I questioned whether I should embrace local themes, issues, or events, or whether I should aim for ambiguous settings with universal ideas; the premise being that writing universal stories might make it more likely to reach an international audience.

Early in my writing career, like many other authors here, I questioned whether I should embrace local themes, issues, or events, or whether I should aim for ambiguous settings with universal ideas

Anecdotally, I’ve been told that our biggest potential markets resist our products because we cannot easily be on the ground in the United Kingdom, US or elsewhere to do school visits and festivals and generally promote our titles. Tyranny of distance rears its head again. Yet other countries have no qualms about offering their books to us sans authors/illustrators available to pop into schools and so on. And what’s more, we take them.

Statistics suggest that Aotearoa New Zealand children’s literature makes up around 12%* of all sales of children’s literature in this country. That’s 88% of sales going to foreign titles, but I have to remind myself that this 88% is made up of lots of different books, from different authors, from a range of different countries. It doesn’t mean that every overseas author is selling into New Zealand. We are getting a curated list here too, and books that arrive will have been brought in because their content will have been deemed relatable and saleable. I’m not going to include ‘high quality’ as a prerequisite because frankly, results do vary. But a publisher here took them on because the business prospects were favourable.

Is our relatively low local market share part of the issue? If overseas publishers look at our print runs and sales as a measure of our desirability then having a small share of a small market does New Zealand authors no favours. I estimate Australian children’s authors have roughly three times the market share in their home country compared with New Zealand sales of their Kiwi counterparts.** Imagine if we had that here. It would be a win all-round if the market share for New Zealand books was increased here. But how?

A literary equivalent of NZ Music Month, which saw a remarkable transformation in the music industry here, would be nice. NZ Music Month—and the playing quota simultaneously required of radio stations here—turned a struggling industry around, but there is no easy transferability of quotas for our literature. You can’t make bookshops sell a particular amount of local titles, although it would be interesting to see what impact less ghettoised shelving of New Zealand books would have on sales. If books were just all shelved by author/book type irrespective of the nationality of the author, would the punters choose differently? If we did NZ Book Month again (it didn’t catch on the first time), what could we impose to increase local book sales? Maybe the media need to get involved.

Even if we could demonstrate big sales here, several sources have said UK publishers don’t want to publish a New Zealand title unless they can also have NZ and Australian rights. So if you are published here first, that rules you out. But then if you try UK publishers first you aren’t on the ground there to visit schools and guest at festivals, which rules you out. Anyone feel like they’re going round in circles? So while David Walliams pushes us off sales here, we have virtually no chance of fighting back. I must admit, this does my head in. My writing has been influenced by my significantly British reading diet growing up. I think some of my books would be a good fit in the United Kingdom, but we’ll probably never know.

If everyone stepped up to talk us up, and our market share grew here, we’d have an even healthier local industry which would be good for all of us

There may be a glimmer of hope on the horizon. A publisher I talked to said that there had been some encouraging upwards trends in international rights sales for New Zealand titles in recent times. At this stage it’s hard to know how real this is or what impact it may have.

There’s a final nail in the coffin of our desire to go international—our ineligibility for many of the big awards that might make our work more desirable to overseas publishers as they create marketing around short-listings, awards and other honours. Unless you have dual nationality and can enter the awards of another country, there are few international accolades available to us. The prestigious Carnegie medal is an exception, but that also comes with fish hooks. Eligibility requires that ‘titles must have been first published in the UK or Ireland between 1 September and 31 August of the previous calendar year. Books first published in another country must have been co-published in the UK or Ireland within three months of the original publication date.’ This is an egregiously small window of opportunity, and see previous reasons for the likelihood that we could ever sneak in this window. We’d have to break a few louvres and even then we probably still wouldn’t fit through.

What might be done to improve our lot? A writer friend suggested a Commonwealth Children’s Book Prize might be a game changer, but this might still favour the United Kingdom and Australia over minnows like us. Would it help enough of us to make a difference? And who would fund and organise it? Closer literary ties with Australia might boost us but what would the benefits be for them over and above what they have now? Their market share at home outstrips ours significantly and we can’t necessarily offer them big sales numbers here.

Should we expect more? It’s hard to know. Our children’s literature is world-class. Sure, not every book is a gem, but that is true of the literature of any country. Whether we are writing about unique aspects of this fair land, or about universal themes and truths, we can foot it with the best. But we are at a distinct disadvantage—our geographical location works against us on a number of levels, from making our participation in promotion and competitions all but impossible, to restricting our participation in the global marketplace and negatively influencing the economics of taking us on. Perhaps in these circumstances we are doing okay, but it never hurts to strive for more. A better profile for our local children’s literature in this country would be a good start. If everyone stepped up to talk us up, and our market share grew here, we’d have an even healthier local industry which would be good for all of us. And maybe a local industry that shines more brightly might get the attention of those further afield.

Footnotes

* Some years back I read an article which put numbers to our market share here but this is unfortunately now lost in the mists of time. I recall adult fiction being around 6-7%, children’s fiction being roughly double that, and non-fiction at least doubling children’s fiction. A recent Newsroom article had adult fiction at 5% compared with the Australian adult fiction market share at 30%. So 12% for NZ children’s fiction sales here is an educated guestimate.

** I believe, as with children’s fiction here, Australian market share for children’s fiction is higher than adult fiction so that would make it in excess of 30%. I’ve assumed it is around 40%.

Melinda Szymanik

Melinda Szymanik is an award-winning author of picture books, short stories and novels for children and young adults. She also writes poetry for adults and children, and regularly teaches creative writing. Recent titles include Lucy and the Dark (Puffin [Penguin RH], 2023) and Sun Shower (Scholastic, 2023).