The New Zealand English school curriculum is undergoing a rewrite and some of the changes suggest a move backwards rather than forwards. High school English teacher Susan Briggs questions who this rewrite prioritises, and describes how English teachers are perfectly placed to select relevant texts for their students.

According to the media on Thursday, the English curriculum for Year 7–13 students is undergoing a rewrite: a prescriptive rewrite that can only be described, in my opinion, as a kick in the guts to both English teachers and students across Aotearoa.

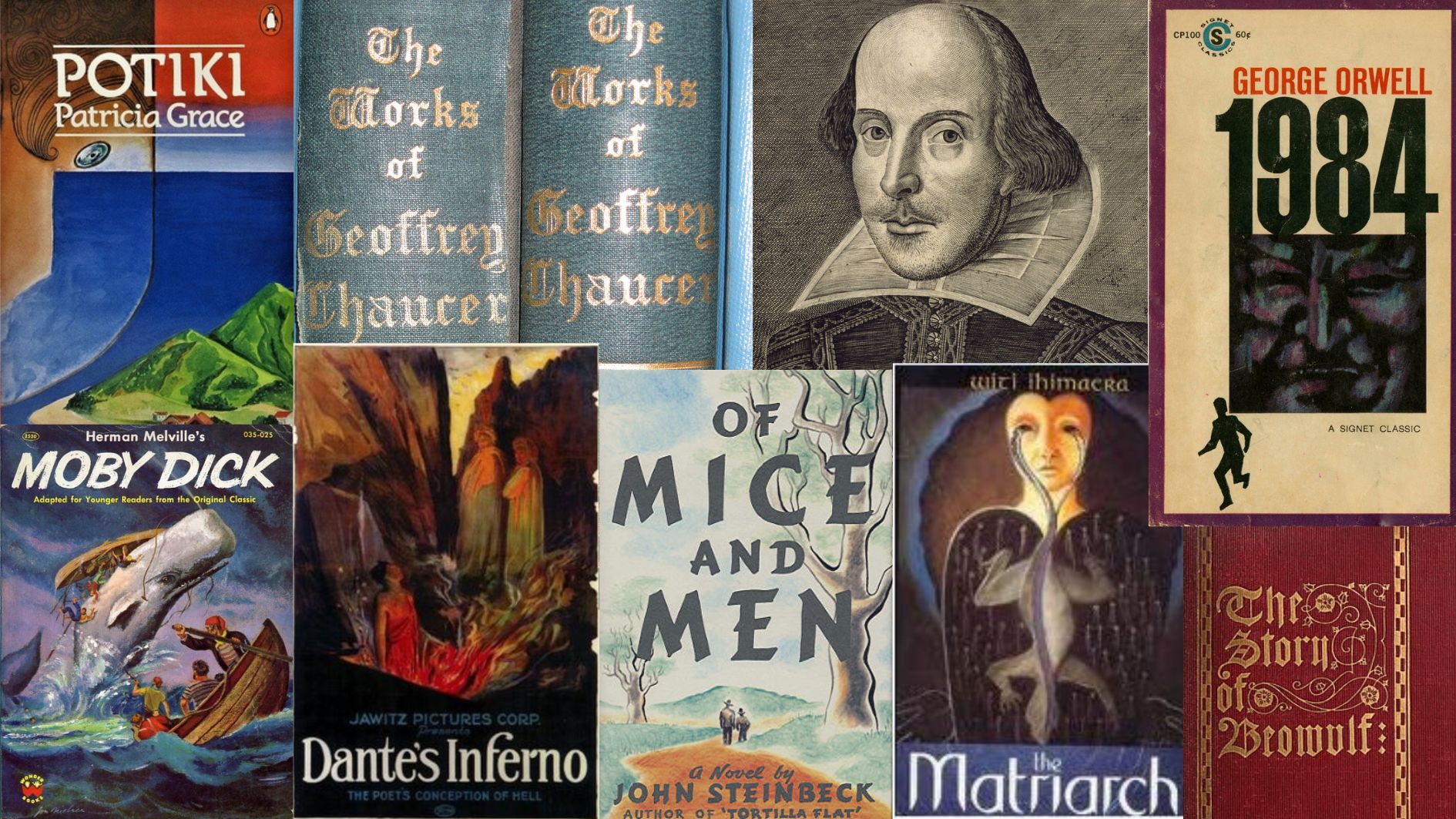

Apparently the government’s move to push a ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ will result in every child throughout the country accessing “the very best English language and literature.” And so it must be asked—the best according to whom? Who decides what the “best English language and literature” is? Whose knowledge—and whose English—is being prioritised here?

The rewrite is being undertaken by a government-appointed, Ministerial Advisory Group’s ‘writing team’ that includes only five people: three teachers from elite Auckland schools, one from an Auckland intermediate school, and Elizabeth Rata from the University of Auckland. So, five people, who have never even met my English classes, believe they are in the best position to decide which texts I should be teaching my students.

There is no respect for teacher professionalism in this rewrite.

As for whose knowledge is being prioritised here, it looks like it is predominantly white colonial knowledge. From the texts mentioned in the media release, the recommended text lists will include a mixture of the old Western literary canon, with a sprinkling of two well-known Māori authors in the mix. Rata stated that, “Shakespeare’s plays would be compulsory for senior secondary students.” But a mandate to privilege Shakespeare above all other authors is nothing new; in fact, it is a relic from the 1990s. For many of us old enough to either sit or teach Bursary English, this is simply a step back into the past.

There is no respect for teacher professionalism in this rewrite. Rata said, “Teachers can’t be curriculum designers as well as teachers,” but English teachers—like Drama teachers and Social Science teachers—most definitely are curriculum designers as well as teachers. English teachers spend hours labouring over their year plans and unit plans, and those first decisions about which texts to teach are ever-important ones. We carefully consider—and discuss animatedly in staff rooms around the country—which texts might be the best ones for our ākonga. We love literature! And we love talking about the pros and cons of the texts in our bookrooms, and which have the greatest literary qualities. We also love teaching texts that we are passionate about, and transferring that passion to our students. We want our students to be challenged; sometimes that means we teach texts that our students would never consider studying themselves. But we also want literature to be accessible to all of our students, and we want students to engage with and connect with the stories and the characters. It is a hard balance, and we do our very best to get it right each time, like the professionals that we are.

Often, English teachers-cum-curriculum-designers become our Heads of Departments/Faculties. They make thoughtful, measured judgments about which sets of texts and novels to buy, in order to meet the needs and interests of the schools’ students. HoFs and HoDs also set clear guidelines for their departments around the provision of a range of language and literature experiences across the various year levels and courses. Our HoDs and HoFs are some of the best curriculum designers out there.

Students want their learning to be relevant to their lives, and as an English teacher I want the texts I teach to be relevant to my students.

There appears to be no consideration of student engagement or agency in this rewrite. English teachers work hard to get to know their students, to develop those important teacher-student relationships, and to figure out how to engage the most disengaged of readers and writers in their classrooms. Personally, I really enjoy teaching plays by Shakespeare to senior students—to students who enjoy studying his plays. By Year 12, many secondary school students have been exposed to some of Shakespeare’s works; however, they don’t all love studying them. And that’s okay. Currently, secondary schools in Aotearoa are able to give their senior students a choice about which English course they would like to take. If a student would rather not study Shakespeare’s plays in Year 12 or 13, then there are other courses on offer that will be equally thought-provoking and challenging in content, and much more engaging for that student. In reality, the vast majority of students that take English at Year 13 don’t wish to continue studying Shakespeare, and since Year 13 English is no longer a compulsory subject in many schools, it makes sense that we provide students with options to suit their interests and needs.

Students want their learning to be relevant to their lives, and as an English teacher I want the texts I teach to be relevant to my students. We have an increasingly diverse population here in Aotearoa, and I enjoy trying to reflect that diversity in the literature I teach. I want my Māori and Pasifika and Asian students to see themselves in the texts I choose. I also want my LGBTQ and neurodivergent students to see themselves in the texts I choose. And in a world that is seeing a shift towards shorter, often more visual texts, I see it as our responsibility to encourage students to continue to engage with extended texts; not discourage them by dictating a narrow range of literature, written by a narrow selection of authors, with a narrow range of protagonists.

How can we ensure that the worldviews of the rangatahi in front of us are going to be included in this rewrite?

Unfortunately, the rewrite seems like a push to make the New Zealand English curriculum more like the UK English curriculum—or the Cambridge English curriculum—where set texts are often prescribed at each year level. But Aotearoa New Zealand is not England, and New Zealand English teachers and students deserve better. Where has the wider consultation been on this issue? Both NZATE (New Zealand Association for English Teachers) and tangata whenua should have been consulted, as well as a range of schools from a variety of regions and deciles. How can we ensure that the worldviews of the rangatahi in front of us are going to be included in this rewrite?

One of the greatest things about the NZ English curriculum has always been that there are no prescribed texts. Let’s hope that this rewrite is not the beginning of the end of our ability to develop nuanced, tailored programmes for our ākonga.

For responses from some of Aotearoa’s creative practitioners, see here.

Susan Briggs

Susan Briggs is a secondary school teacher. Born and raised in Whanganui-a-tara, she now lives with her family in Ōtautahi. She has been teaching English since 2005, and completed a MEd in literacy in 2020.