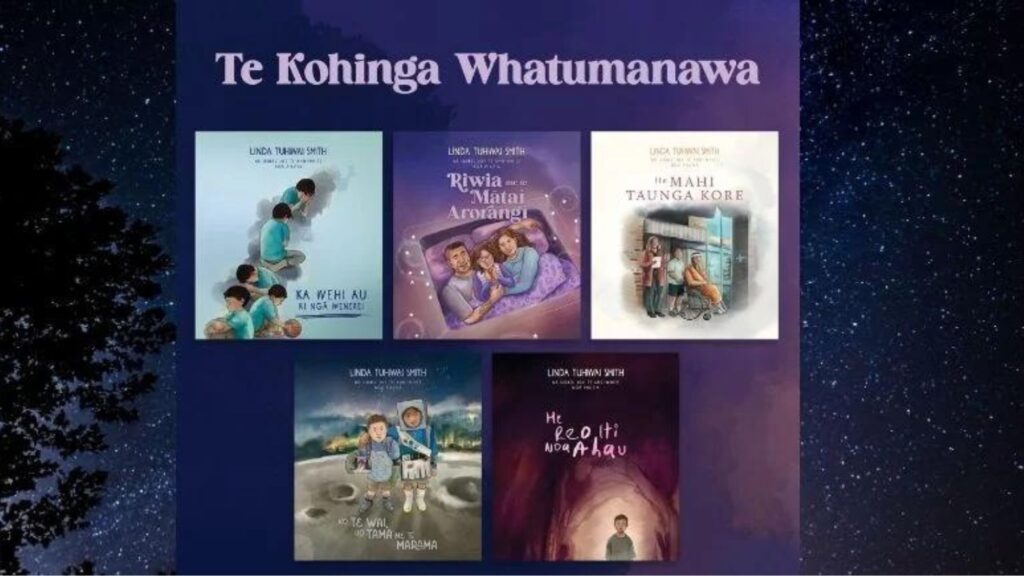

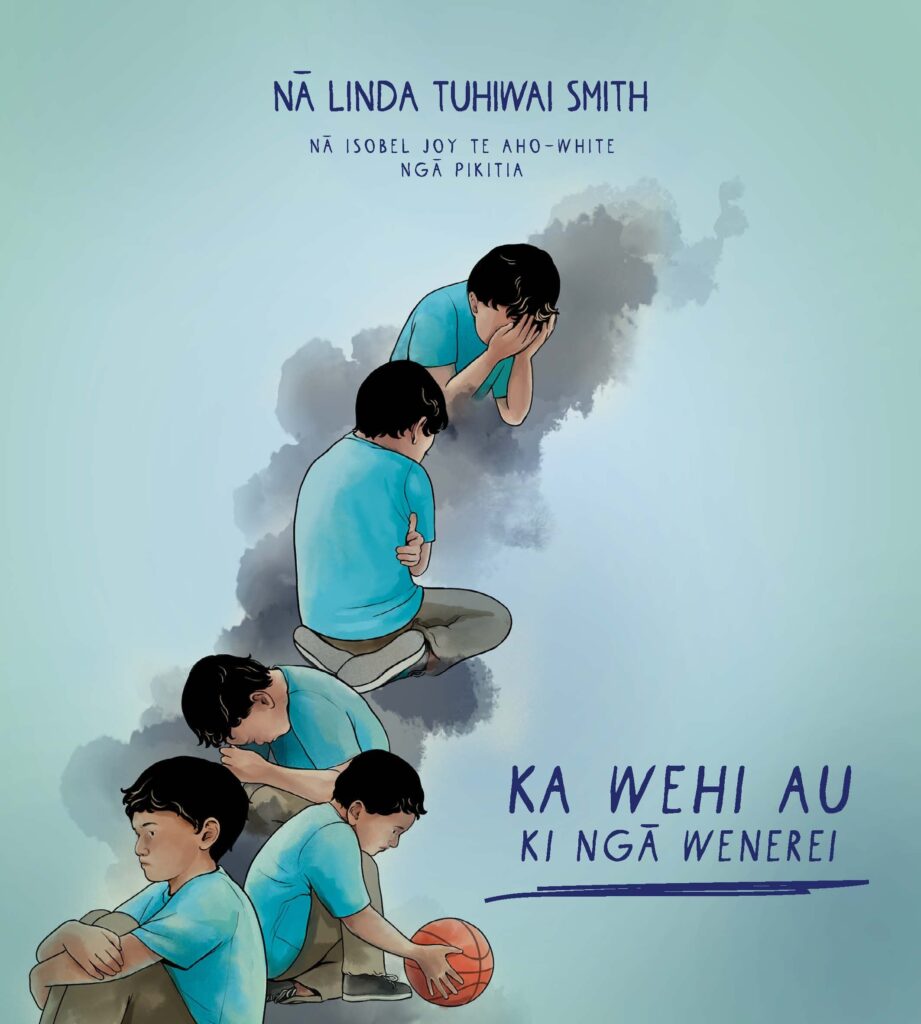

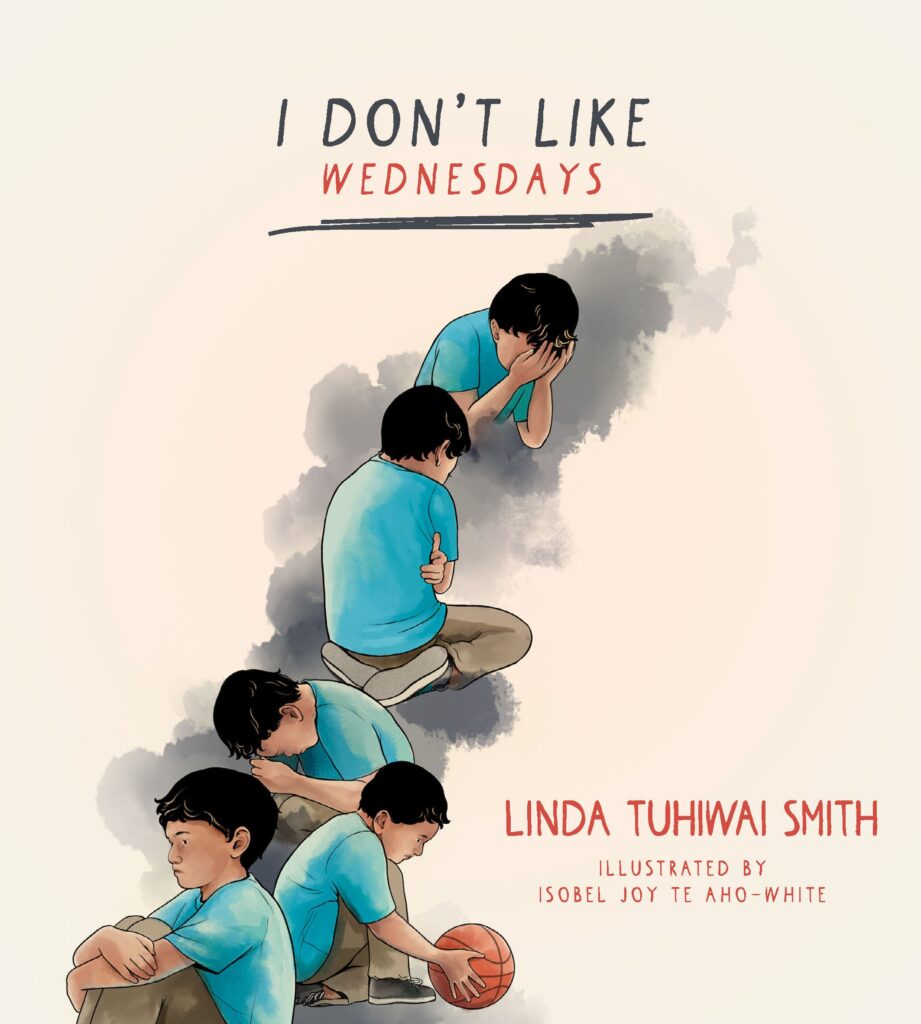

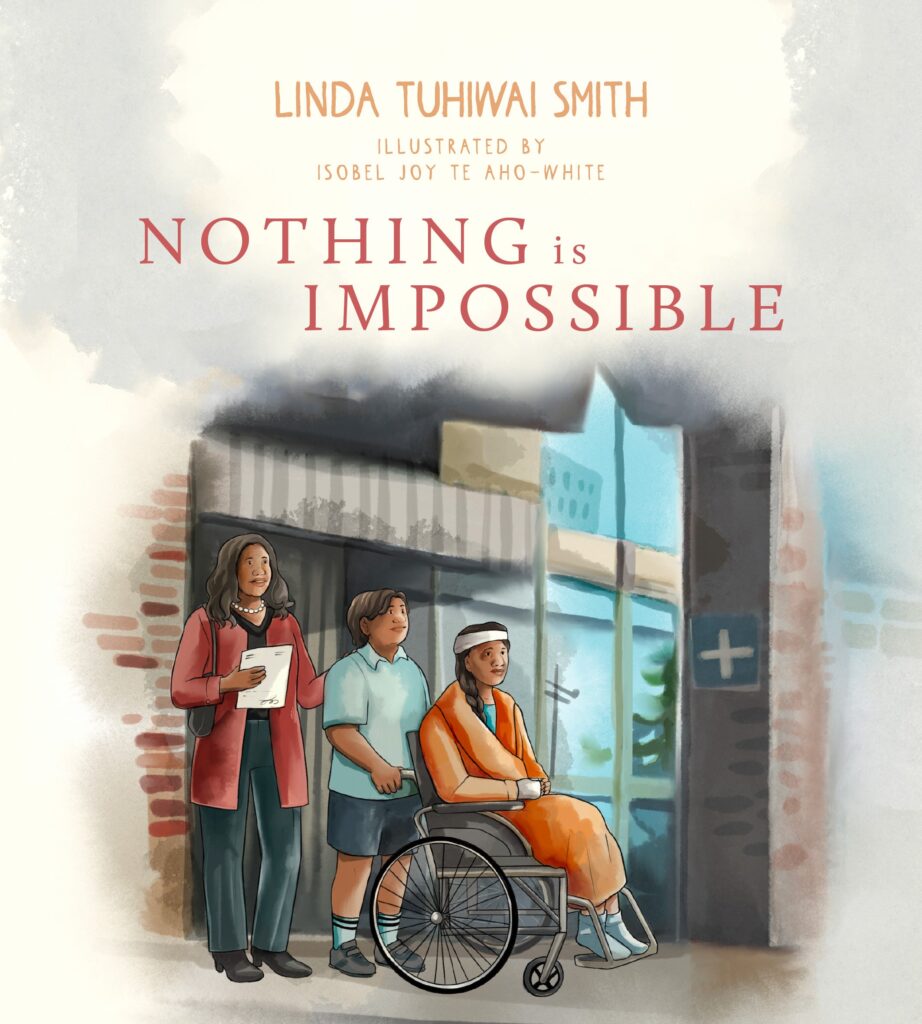

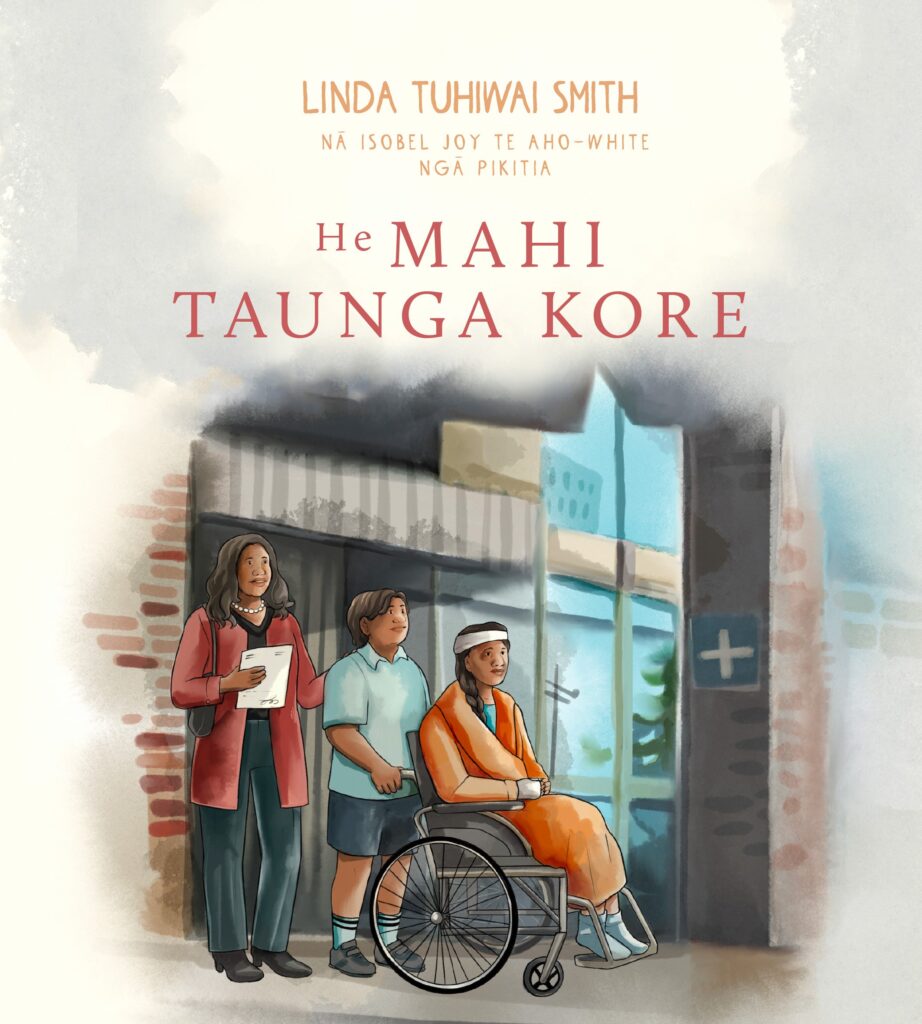

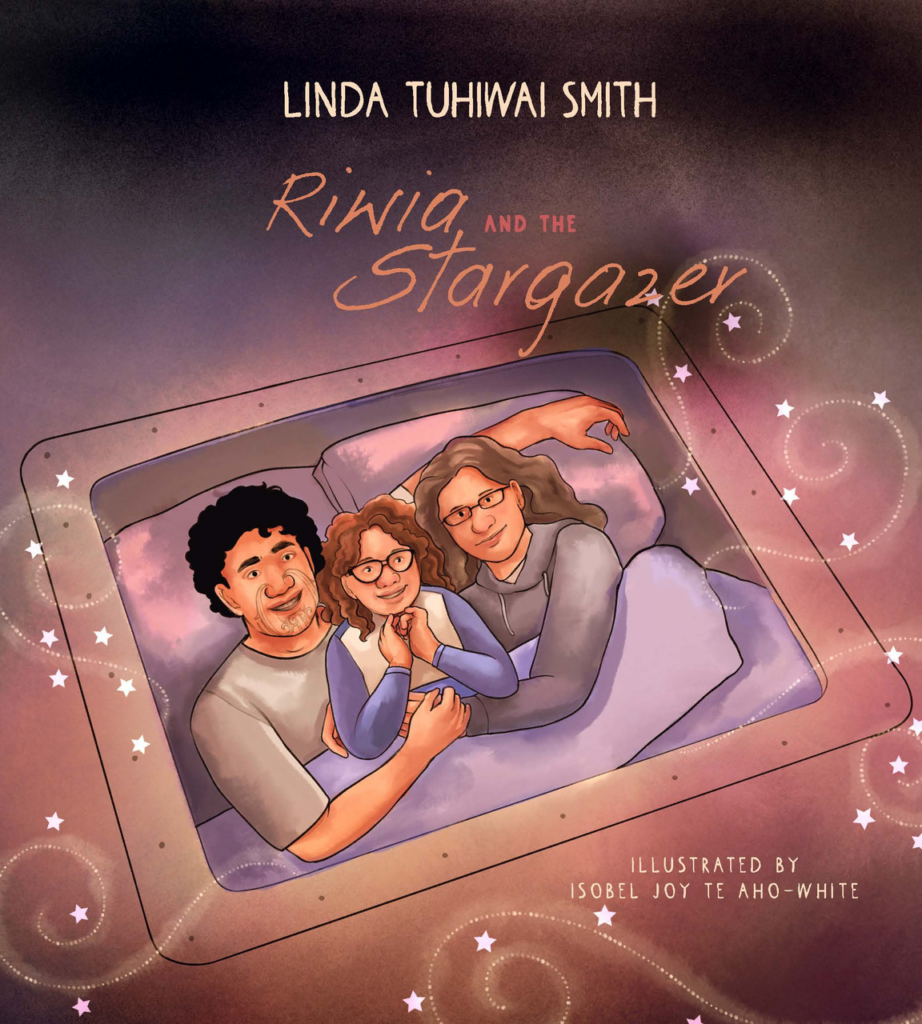

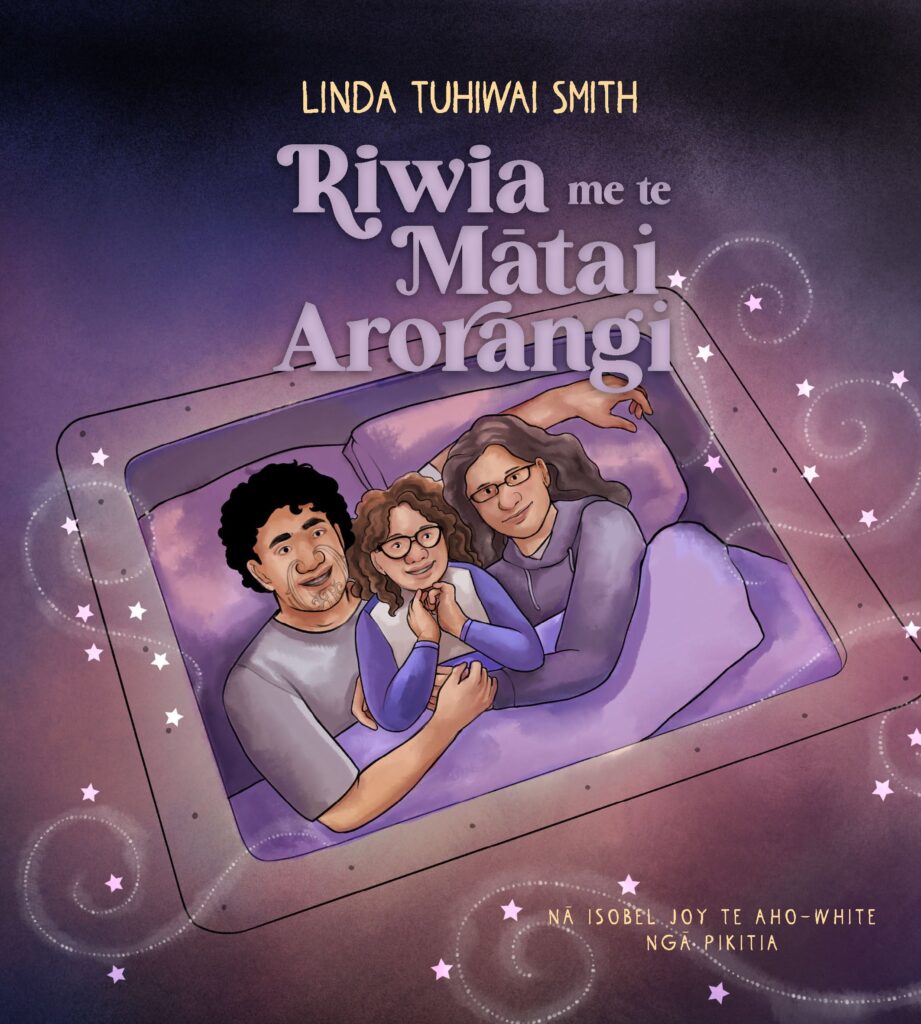

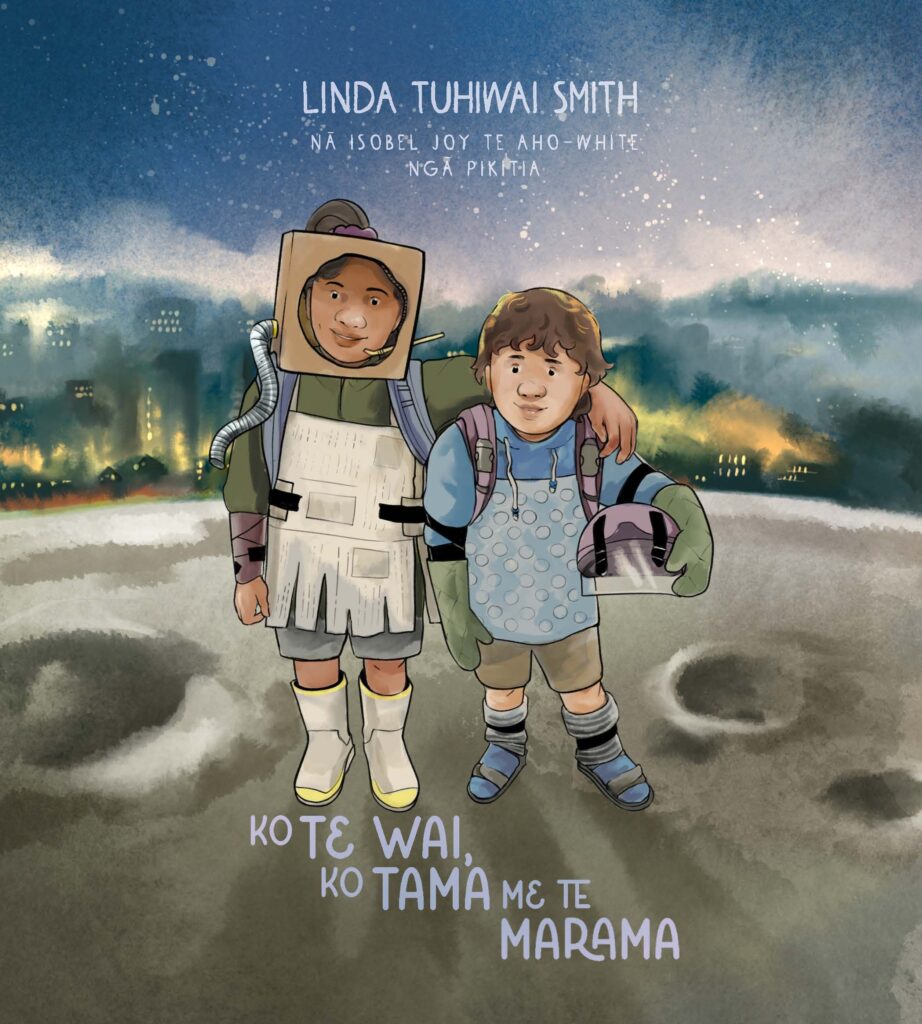

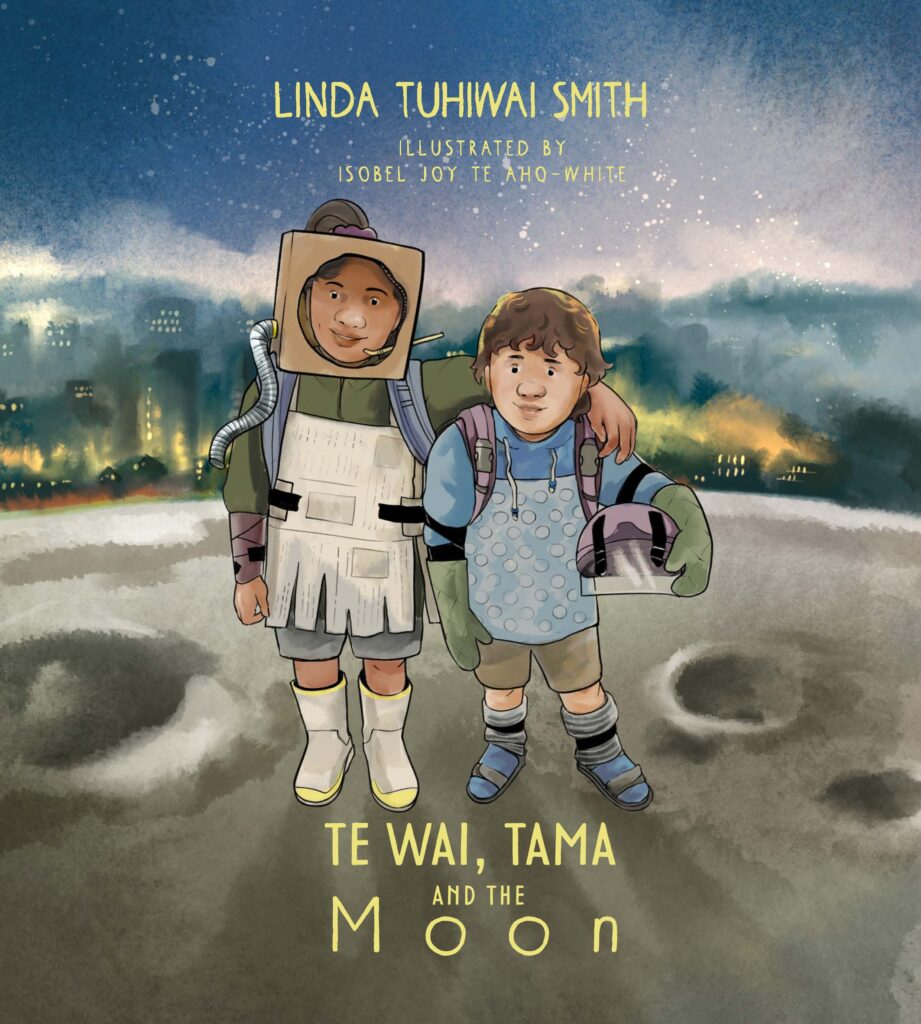

Linda Tuhiwai Smith is renowned in her field – indigenous education – and now has authored a series of picture books dealing with social issues, the Whatumanawa collection, available in both te reo Māori and reo Pākehā. They are serious, heartbreaking, and powerful tools for addressing the trauma of difficult and painful experiences – a really valuable resource for supporting our tamariki. Linda Jane Keegan puts forth some questions for Linda on the series.

You’re well-known for your academic work in indigenous education. What made you decide to write for children?

My recent research with colleagues such as Leonie Pihama has been in healing from inter-generational trauma. I noticed that there was very little, actually no literature that directly spoke to children about a trauma even though tens of thousands of children experience or witness trauma. The stories just started to come to me.

These books cover very heavy topics – suicide, death, long-term illness, domestic violence, and abuse – how do you imagine them being used with tamariki?

With an adult preferably using the story as a way to elicit conversations and as an opportunity to address something very painful – for which I know many children have no vocabulary for. However I also know that adults can be gatekeepers for children so it may be a child, even an older child will pick up a book and it may help them understand an experience.

It takes a whole society to raise children, a whanau, hapū, iwi and wider community.

You have beautifully woven in the interconnectedness of whānau and how different people share the responsibilities of looking out for the children in these stories. Can you tell us about how this reflects real-life whanaungatanga?

It takes a whole society to raise children, a whanau, hapū, iwi and wider community. New Zealand is terrible at it. I see whanau as the solution and support system for a child if adults can get over themselves and focus on the well-being of children. I also recognise that many of our tamariki live in contexts where their whanau is their neighbourhood, their school or sports club.

Māori are vastly over-represented in statistics around suicide, abuse, and domestic violence. Can you tell us more about the people you chose to represent in these books?

The specific trauma of each story wasn’t planned out. The story just came into my mind usually while I was driving long distances. I visualised the people. I saw all the characters as Māori, the ones who caused harm and also the ones who can heal and rebuild confidence. I saw the tamariki and their whanau as being diverse, not reflecting some stereotype of a Maori person or child. I wanted to show that our papas could be a bit funky or vulnerable and good fathers. And I wanted the children to look different, glasses, freckles etc.

I have heard already that the books make adults cry. I hope it helps adults to understand their own pain and trauma and to find a way to ensure that children are better supported in their healing.

Maybe in part because of my own past experience of having a premature baby in special hospital care, I sobbed when reading Riwia and the Stargazer. Do you think these books will also help the adults who are reading with children with processing their trauma?

I cried myself when shaping each of the stories. I have heard already that the books make adults cry. I hope it helps adults to understand their own pain and trauma and to find a way to ensure that children are better supported in their healing. Life can present us with harsh lessons which we can learn from and develop insight and resiliency or we can get stuck and carry the hurt into our adulthood and it can cause more harm.

As a writer, how do you protect yourself in regard to coping with the mental health aspect of submerging yourself in these distressing situations?

I don’t know. Most people don’t believe me when I tell them I am reserved, was very socially awkward in my early adult years, tend to be empathic and cry in movies or while watching tv. I have had to learn to speak publicly as a teacher and lecturer and to engage socially in the world. I am quite happy being on my own and am now also happy to socialise with others for a while and then go home again. I am a reader with wide tastes from crime thrillers to cook books, poetry to academic texts.

If people think the topics aren’t suitable for children then how would address the fact that somewhere a child will be experiencing these things every day somewhere in Aotearoa.

Do you anticipate receiving any pushback from people who may be concerned that the content of these books isn’t appropriate for children? How would you respond to such feedback?

I consulted with many people over these books, parents, psychologists and people who work with trauma in communities. If people think the topics aren’t suitable for children then how would address the fact that somewhere a child will be experiencing these things every day somewhere in Aotearoa. For many children it will be part of a systematic and enduring set of experiences before they are pulled away from them. Literature is a great way to help children gain insight.

Is there a place for using these books with children who haven’t experienced trauma?

Good question. Yes because you need children to understand what is happening to their mates and we need everyone in society to understand so they are compelled to stop it.

Literature is a great way to help children gain insight.

Can you tell us about the collaborative process between you, the illustrator, and the publisher? How did you navigate the process, given the sensitive content of the stories?

The publisher was excellent, constructive and respectful. I had to work with editors, experienced children’s book writers I think, and then the language editor. I welcomed their feedback and I found the editing process interesting as it made me think about every word and the role of the words and the illustrations. I did not interact directly with the illustrator but responded to drafts and tried to give useful directions. Actually I found it hard writing a children’s book compared to the academic writing I am trained to do. When I was a teacher way back in time I did do courses on children’s literature and read novels as a daily serial to my intermediate school, mischief pupils.

Do you intend on doing more work in this space, for children or relating to trauma? Or what else are you working on, for children or otherwise?

I’m getting requests for other trauma topics to write about but I’m just sitting on them at the moment. I am doing some research that could grow into a children’s novel. It depends what stories come into mind really.

The Whatumanawa Collection is published by Huia Publishers, and illustrated by Isobel Joy Te Aho-White. Books are $22 each and available here.

Linda Jane is the lead editor of The Sapling, a parent, and a writer of picture books, poetry, and other tidbits. Her background is varied, including work in ecology, environmental education, summer camps, and a community newspaper. She is Singaporean-Pākehā, queer, and loves leaping into cold bodies of water.