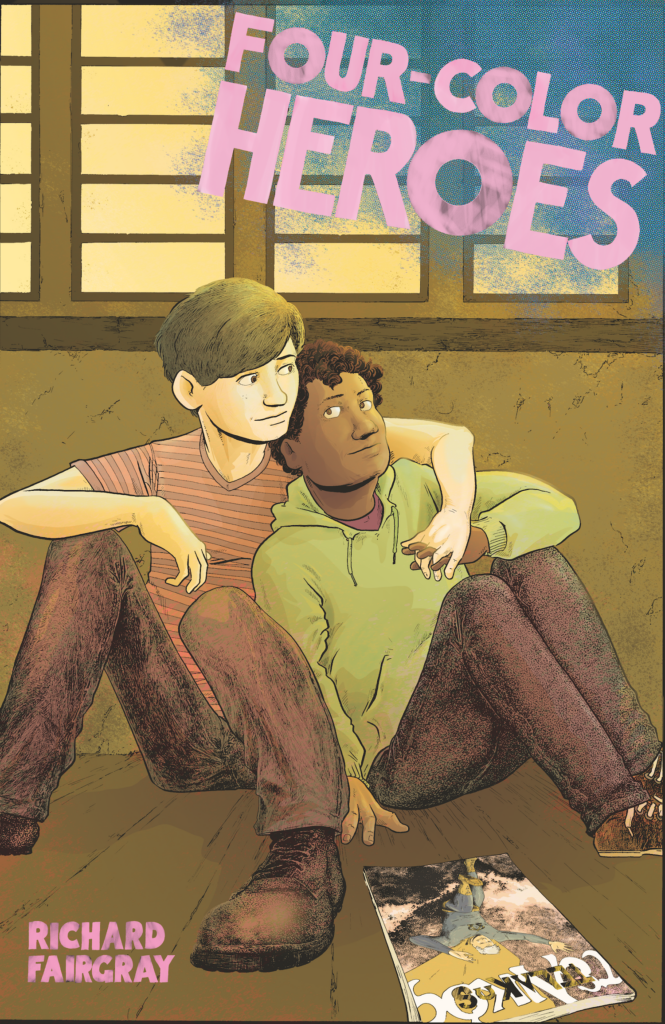

Richard Fairgray is an award-winning creator who has published over 200 titles, ranging from children’s books like Gorillas in Our Midst and My Grandpa Is a Dinosaur to graphic novels like Black Sand Beach, Blastosaurus and Cardboardia. Here, Charlotte Fielding talks to Richard about his latest work, Four-Color Heroes. It’s a touching love story which follows two star-crossed young men who—in spite of their disparate backgrounds—find escape and one another through the pages of a comic book. The coming-of-age romance is set in a New Zealand high school prior to the passing of the Civil Union Act 2004 (which allowed same-sex couples to enter into a civil union). The graphic novel will be made available digitally in both English and te reo Māori as translated by Komako A. Silver and Alejandra Jensen (The Art of Taonga Puoro), to be released in English-language print in June 2023. Four-Color Heroes is an LGBTQ+, Upper YA graphic novel, and you can read an excerpt here.

How did you come up with the idea for Four-Color Heroes? What inspired it?

I have been sitting on this idea for a little over a decade. I’ve read a lot of books where other comics get integrated into the storytelling, and I always hate the way it’s done because it feels like you’re enjoying a story and then suddenly you have to stop and read a comic. I had this idea that people who don’t like comic books still enjoy hearing about comic books from people who are enthusiastic about them, in the same way that, like, I do not like cricket. But if cricket is your favourite thing in the world, you can probably make it interesting for me because of the passion you have for it. I started thinking, a cool way to get stories across or to engage people in the massive back story that is a superhero comic is to let someone enthusiastically ask them about it rather than force them to know the facts.

It was around the time that gay marriage, as in gay marriage proper, not just civil unions, had just become legal. And I had a few pretty big fights with people in my life about that. Those are people who are not in my life any more, shockingly. And it was also around the time that there was a lot of attention on places like the Westboro Baptist Church. This idea just kind of sprung to me that there are so many pieces of of media that we escape into and comic books have been a big escape for me for a really long time. Growing up as a weirdo queer kid in New Zealand, comic books were stories about people with secret identities, people who were more special and wonderful than we could ever hope to be. And honestly, deep down, I believe that about myself, and as a teenager I did too. All of those feelings bubbled up and I was sitting with a friend of mine having lunch and I blurted out the entire concept in about five or 10 minutes. Little pieces of it have changed, but the beginning, middle, and end were all immediately there.

What was significant about it being set prior to the Civil Union Act? How might things have changed for the characters after the Act was passed?

Originally I had this much bigger plan to tell the story very quickly. I am a workaholic and I’m under contract to draw 988 pages of comics this year. When I pitched this book, the publisher had seen my other title, Haunted Hill, and really liked it. And I said I’ll do it in that style because I can draw about 3 or 4 pages a day of that. It’s pretty quick. When I started writing the script, it was going to be set in a generic time and place. The story was about the boys falling in love. It was about the comic books. It was about the kind of distant idea of repressive religious families and toxic masculinity. But it wasn’t going to be particularly grounded in anything other than their connection with each other.

I was having a lot of trouble with it because I am not from a particularly religious background. My parents tried to dip into the whole church scene for a second, but my sister kept getting us kicked out of Sunday schools for beating up other kids. And I realised, why was I trying to write it from this kid’s perspective when actually the kid from the “bad family”—to use shitty language around it—was far more like me. I thought, well, OK, I want to catch a certain tone. I was really into reading comic books in the early 2000s, and I was just starting to teach high school in 2005. And so I thought, you know, it can be hard for a lot of people to capture what young people talk like. And you always spotted that a mile off. But I think that I can pretty accurately capture the kind of conversations that I was hearing then.

I started realising as I was writing the script that this felt more special than most of the other books that I had been working on

Not to build myself up too much, but I started realising as I was writing the script that this felt more special than most of the other books that I had been working on for quite a while. I was getting very emotionally involved with it. The characters were really coming alive in a way that I hadn’t expected. And I thought, I need to know everything about these people. I want to feel like I am deeply entrenched in their lives. I want this to feel based on something that I know. And so I thought, this is going to be it. This is going to be the book that is set in New Zealand.

I hadn’t even run that part past the publisher yet. The book was coming out for an American audience primarily. And I thought, well, I think that when you start talking about American religion and American homophobia, it becomes almost cartoonish, right? Both then and now, and almost more so now. And I thought that that would feel like I was just taking really broad swipes at bad people for being bad in obvious ways. And it would become a story about a Westboro Baptist Church or it would become a story about some terrible present-day politician, on purpose or not. And I thought, New Zealand, I was there. I was there protesting those protests. I was there with all of my queer friends being angry and excited and thinking that, you know, Jay and Maya on Shortland St really mattered. It just became this grounded and dense piece. And then what that meant was that if you’re setting something in reality, you have to really set it in reality. And so this book that was meant to take me 2.5 months to do turned into an eight month project.

If I’m drawing a bus stop on Mt Eden Rd, I have to know not what café is across the street from it now, but what was across the street from it then. I have to know what the architecture of the schools was. Just so many little weird details. I wanted to create a sense of nostalgia without saying that nostalgic things are better.

So would you say it involved more research than some of your previous work?

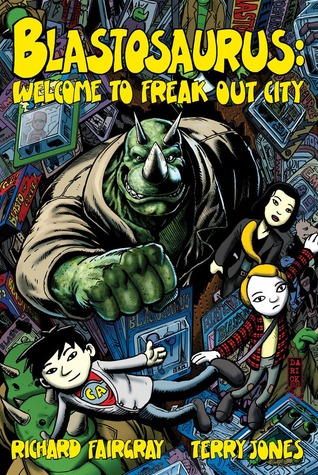

Yeah, I mean, Blastosaurus is about a crime fighting Triceratops. I can make every part of that up. Black Sand Beach is loosely based on my own childhood, as I spent a lot of summer at the Haunted Lighthouse. But there’s no real world where these people are sitting there. It’s human characters in a bizarre place and I can write that by thinking about how people think and how people feel.

But this one, I wanted people to look at it and feel like they were in that place, and I wanted people in other countries to look at it and go, oh this is this is New Zealand.

One thing I’ve really noticed living outside of New Zealand is the sky is a different colour. When I see photos from New Zealand the colour balance is fundamentally different and if I colour this like an American comic it’s gonna look wrong. I start thinking about the language on signs and buses and things like what side of the road the cars drive on. I mean, do you have any idea how hard it is to find what model of Stagecoach bus would have been driving down Dominion Road at 3:40 on a Thursday in 2004? Like the patterns on the chairs inside that bus. They’re very ugly and hard to draw, I’ll tell you that much.

I read on your website that since you were a young child, you’ve been determined to keep writing stories about things you don’t see in other books. What is it about Four-Color Heroes that you don’t see in other books, do you think?

A lot of it comes back to that intertextual storytelling, without it interrupting the actual flow of the story. I think that comics are this amazing medium where you can literally control time. A film will play for the same amount of time for everyone who watches it. A book, it’ll take you however long it takes you to read that many words. But in a comic, I can make you spend longer on a page by giving you more text, more detailed panels, smaller panels, larger panels that have more things to go back to. It’s a small amount of control, but I can control it. And so when you have that kind of power as a writer and an artist, you can do really interesting things. And I want to push those limits with this one, in ways that I haven’t really in other stories.

Originally this was going to be coming out as a six issue series. I spoke with Barbra and Bryant at Fanbase [Press] and we agreed, like I wrote these six equal length scripts.

But there are moments in this that are really important. There’s a scene right around the middle of the book where they’re in this old abandoned house and a box of photographs falls and crashes at the top of the stairs and all these photographs float around. It’s a very small moment and there’s no dialogue and really nothing happens. But I was like, this is a wonderful cinematic moment. I want to give this a full double page spread that is going to throw off the entire issue. I want that issue now to be four pages longer so that I can spend some time showing those photos falling further, falling into a bucket of dirty mop water and sinking to the bottom.

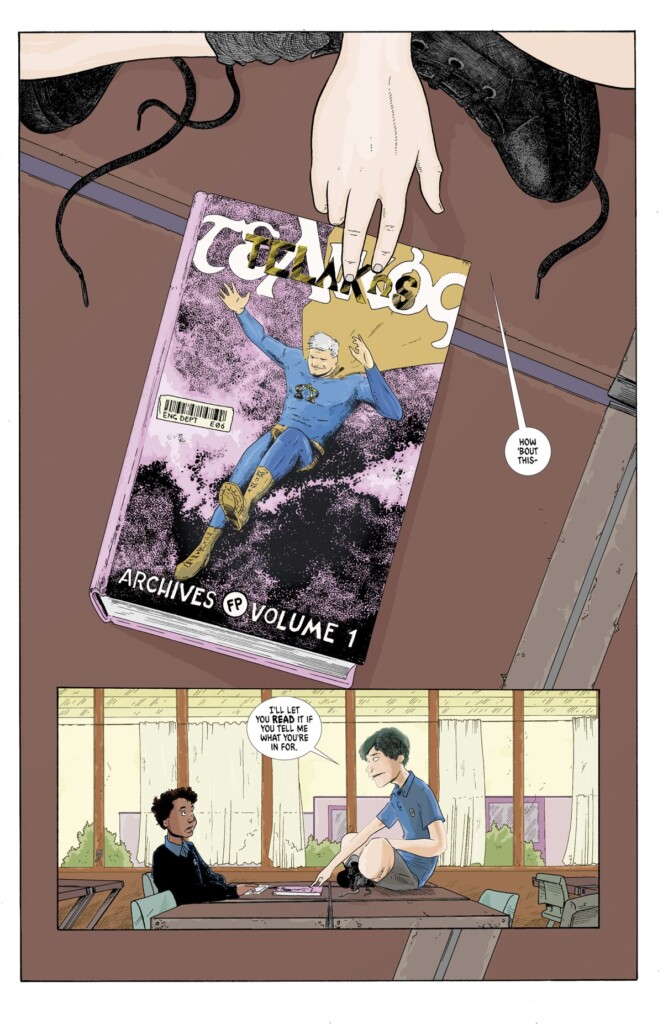

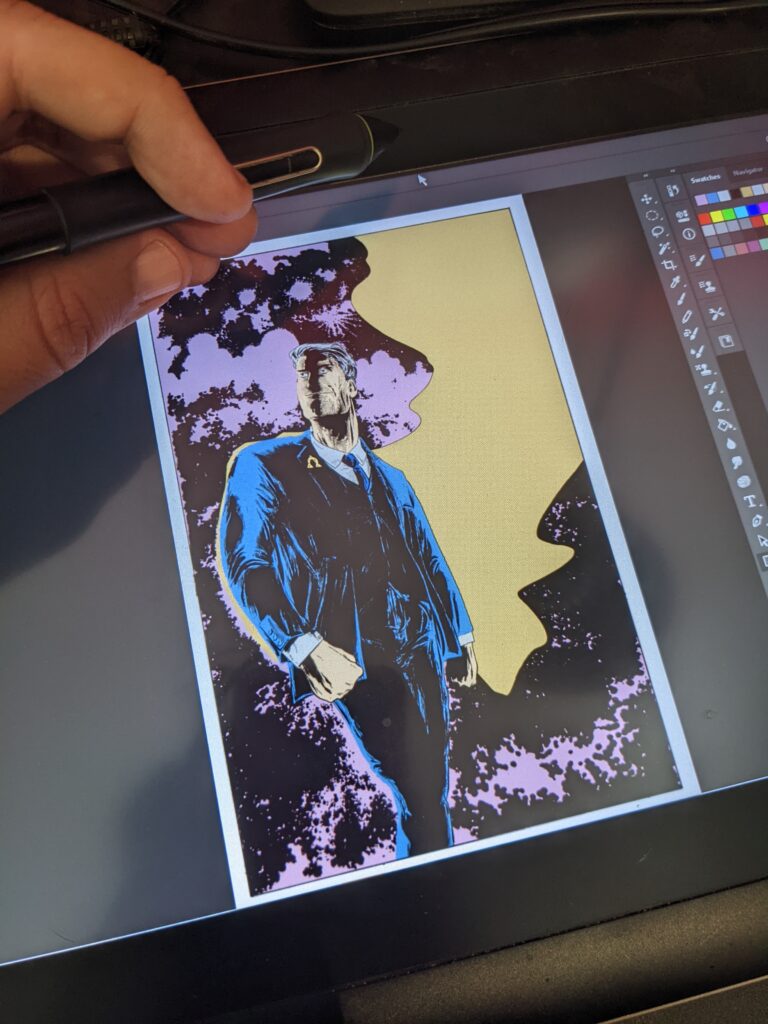

And they [Fanbase Press] were really willing to let me kind of go hog wild on this whole thing and take it in any direction I wanted to. The superhero stories are because Oscar—the characters are Oscar and Patrick—never even let himself look at the superhero books. He imagines them as Patrick tells him about them. And so we see these incomplete and weird understandings of superheroes that look like superhero comics. They’re just a bit wrong.

The first one he hears is about this character who has a suit of blue and gold and so he imagines it as like a business suit, blue and gold with the big cape coming out of it. And they have this whole conversation about how the cape attaches to a suit collar. But then I also get to have the language of the comic because of a 15-year-old boy excitedly rambling about what happened in the story.

It becomes that energy that you kind of lose as you grow up where you are focused on every single detail, but never understanding which ones are more important or less, and so you’re just blurting out all the coolest bits.

So what does the story itself mean to you as the creator? And from that, what do you hope readers get from it?

I want to show that there’s a lot of different ways that bad energy, bad ideas, and bad understandings of masculinity can be interpreted. I am not a fan of religion. Especially not extreme religions that would stop you from doing things like reading comics or being gay, for instance.

I’m also not a fan of the expectations of a tough older brother who doesn’t want you to, like, be the weird queer kid, or the expectations of teachers that because you’re from a family who traditionally get in trouble at school, that you’re going to be the one who gets in trouble at school.

Oscar is rescuing Patrick from a dangerous life in a lot of ways. He’s offering him a way out, and Patrick is offering Oscar the exact same thing. And I wanted to show the two different sides of that coin.

If you’re my age and you’re reading the book, I hope that you look at it and go “I remember what that felt like. I remember what it meant to be a queer kid in the early 2000s.”

If you’re my age and you’re reading the book, I hope that you look at it and go “I remember what that felt like. I remember what it meant to be a queer kid in the early 2000s.” If you are a kid now, I want you to read it and go, “Am I one of these people or am I one of the people causing the world to be harder for them? How many things that are invisible to me because they’re part of my everyday life, like jokes that I think are harmless, or the assumptions about gender or sexuality or people’s roles? Like, can I be a better person?” I want people to look at themselves and say, “Hey, why are people avoiding me? Why are people hiding things from me? Is it because I haven’t made myself a welcoming person for them to be themselves around?” I also want people to know that comics are really cool, and it’s really neat that I have two characters who are so excited about them.

One of the protagonists of Four-Color Heroes has Māori heritage, and so it was important to you that the work was available in English and in te reo. Can you tell us more about that?

So I grew up on the North Shore of Auckland, in a suburb called Torbay, which is like… there were cows over the fence from my school. And my life was white, suburban emptiness. Like every film you’ve ever seen that starts with a teenager in a hoodie kicking a can from their house to the mall. That was my life. I think things are better now. Not right, but different than they were. But I remember when I was growing up, my friend’s mother, she saw “kia ora” written on a sign somewhere and was like, “ohh, what does that mean?”

That same friend’s mother, later seeing the word out written on a glass door, goes, “Oh, this Māori stuff everywhere.” And that was such a normal part of growing up. Same with the homophobia, the racism, all kinds of bigotry. They tend to all just boil up from the same places. It’s “difference is bad”.

Te reo wasn’t integrated into school in the way it is now. It wasn’t integrated into the television the way it is now. And I also grew up feeling really alienated from culture because New Zealand, as far as I could tell, didn’t have its own culture. We had American television or you could watch Channel 1 and get some British television sometimes, and we didn’t have a thing that was specifically our identity, except for these things that my friend’s mother would complain about.

Then I moved to LA and it’s a far more diverse place than Torbay, and there’s street signs in Spanish and Chinese and Korean, depending which part of town you’re in. I live half my life in Canada, where literally everything is in English and in French. It made me feel really sad that I hadn’t grown up in a version of New Zealand that was like that. And again, I think it is much better now than it was 20-30 years ago.

You were born blind in one eye and with 3% vision in your other eye, and you’ve made a career as a visual artist. How would you say that your disability has impacted your work?

My left eye is much smaller than my right, and my right eye kind of wobbles around all the time. I can’t form a focal point and I have real trouble judging depth. And so as a kid, I just started drawing pictures because it was a way for me to 100% flatten the world. It’s why I love cartoons so much, and why I really, really hate remastered video games where they try to make things look more like the real world. It was nice and flat before.

I started drawing pictures and making up stories as soon as I could, and my parents were convinced that I needed to know how to read and write before I started kindergarten, because they were under the impression that all the other kids would know that as well. That’s a real fun way to get alienated on day one.

I have literally a skewed perspective. I have to try and interpret things into what it is like. People will comment on things as being my style and I’ll say, “Oh no, that’s what I thought it looked like.”

So you draw the world as you see it.

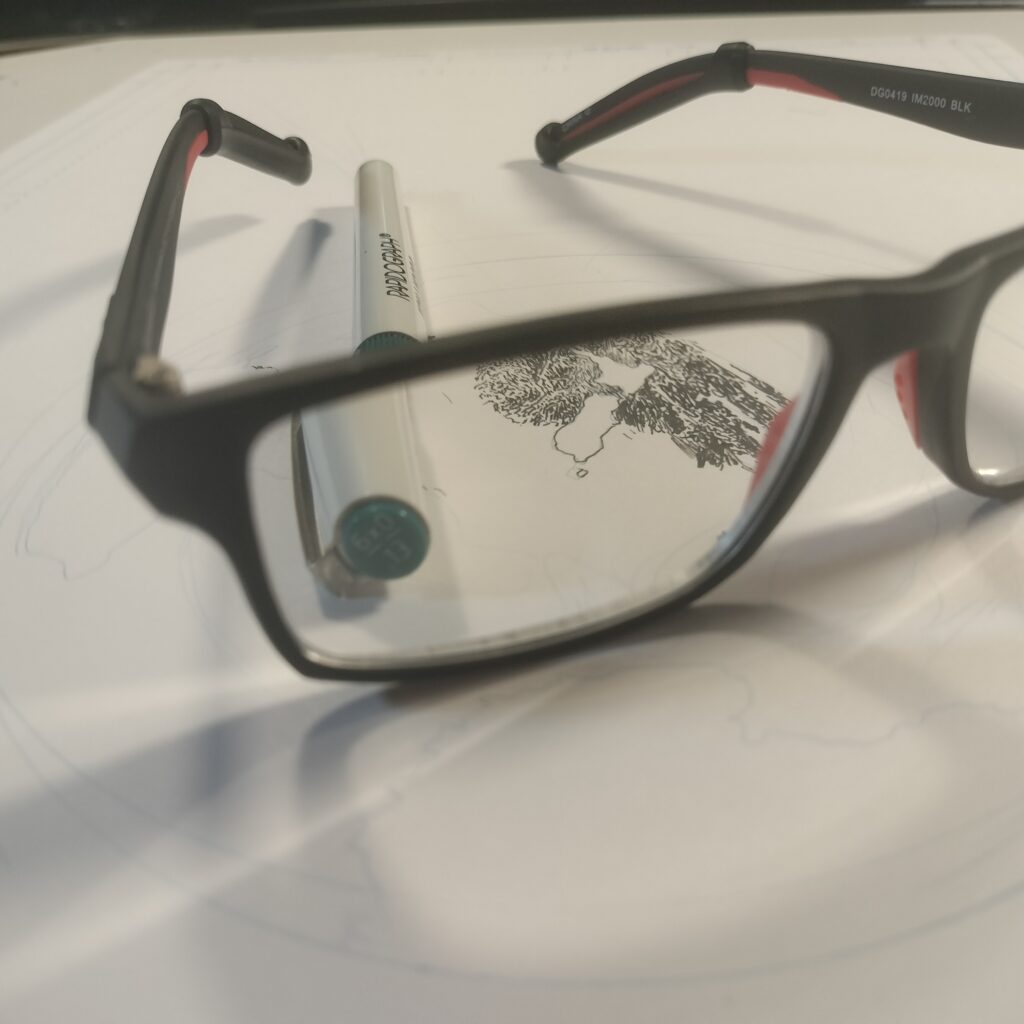

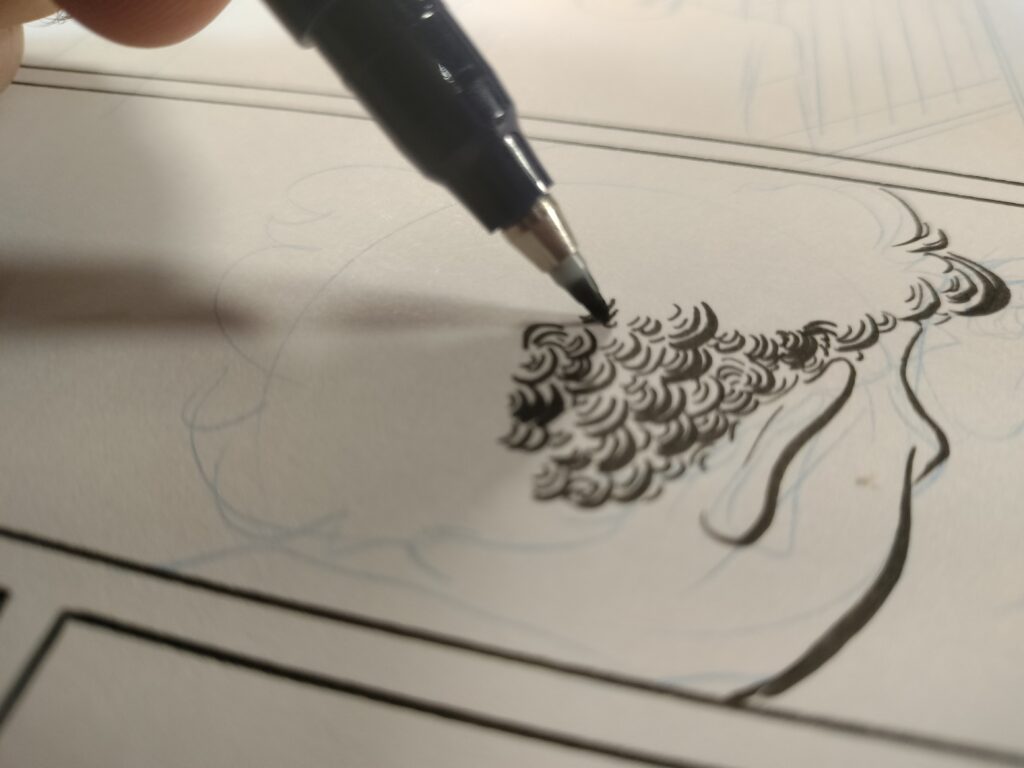

Yeah. And I’m obsessed with details and textures and things to try and overcompensate for that a little bit. So with this book, getting in those signs in the background and the textures on the grass and the right shapes of leaves has meant buying stronger glasses and a headlamp that I have to wear when I draw certain things, and a pen that is so fine that my scanner couldn’t pick it up and I had to get a better scanner instead.

I usually spend 18 to 20 hours a day drawing. The eyesight is actually a side effect of a chemical imbalance so my brain doesn’t go into sleep patterns properly. A thing that would normally have healed while I was in utero didn’t, and so when my optic nerves grew out to attach to the back of the eyeballs, there was nothing to grab onto. I’m always in fight or flight mode, basically. And it means that I just never run out of energy, never really notice if I need to be sleeping, and so I can just work like crazy.

How do you balance writing and illustrating? Do you do them at the same time or separately?

It’s different for different books. With this one I had some pretty stressful stuff going on in real life. And so I dipped out of real life for about a week and went to New York and said I will not be available for anyone for one week. I am going to live that very clichéd lifestyle and go each morning and sit in a café and write one chapter of this book. And then I will walk around New York City and have adventures. And it was the clearest my mind had been for a long time. You know, obviously coping [with the pandemic] has been a nightmare for everyone and certainly worse for a lot of people than it was for me, but that sense of isolation has been so difficult.

Everyone should wear masks all the time, by the way. I am still masking everywhere I go. I have literally 14 vaccines at this point. And I don’t go indoors. I go to my house, I go to my office, and I go for walks.

Normally what I do is, I will write as I’m going. With Haunted Hill, I write a six page sequence at the beginning of the day, immediately do the layouts for it and then start drawing. And I do that every two days until a book is finished. With Black Sand Beach, I will write a rough outline and just start drawing and then fill in dialogue later. So a lot of the time it’s about tricking myself into doing something different everyday.

Is there anything else that you would like to tell people about the book?

We can only handle caring about a certain amount of other people in the world and the world has become so aggressive towards every marginalised group that now we have to care about every single person equally and it’s overwhelming and I think the best thing that I can do is make comics for people who might not have a lot of people standing up for them.

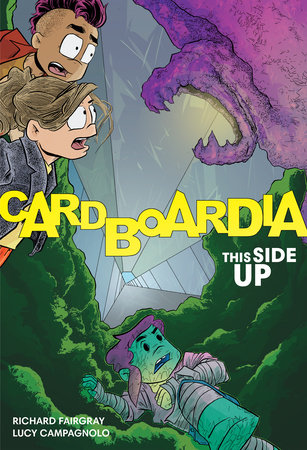

If you can’t wait for June to see Four-Color Heroes, Richard has the second Cardboardia comic coming out in January! Pokey is lost in Cardboardia, and her older brother, Mac, and friends, Maisey and Bird, are desperately trying to find her. Taken in by a band of wild witch girls—friends or foes?—Mac, Maisey, and Bird learn more about how the world off Cardboardia works. What’s in all the boxes? What are the rules of travel?

Aimed at ages 8-10 years.

Cardboardia 2: This Side Up

By Richard Fairgray & Lucy Campagnolo

Published by Holiday House

RRP: $37.00

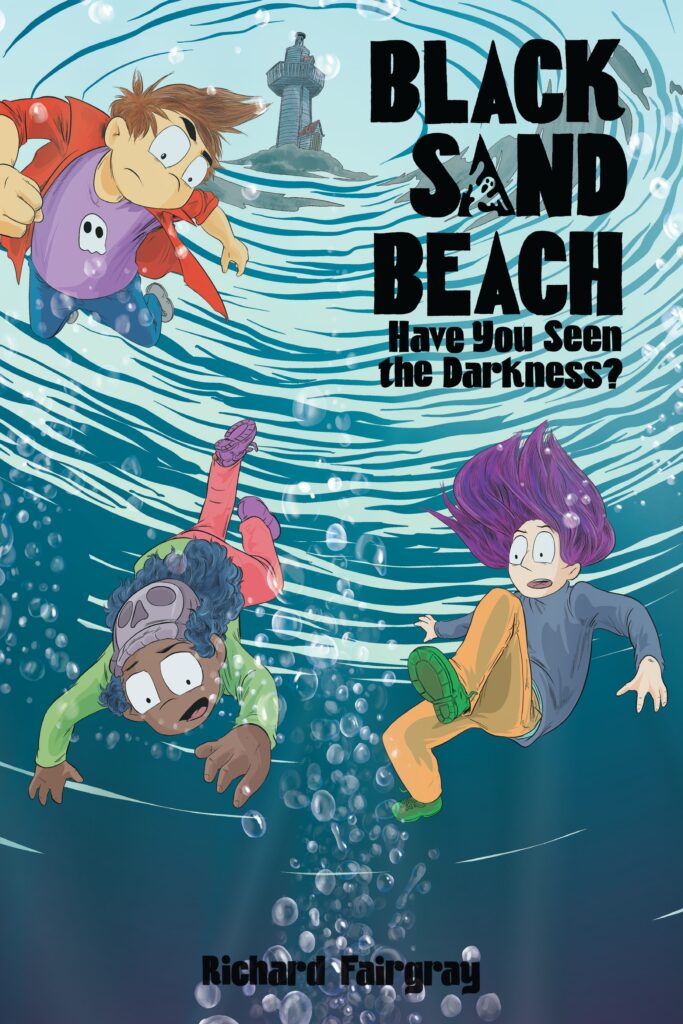

Can’t wait until January? Black Sand Beach #3: Have You Seen the Darkness? came out earlier this year! Dash and the crew are on a mission to save their summer vacation home from competing evils in the third installment in the creepy Black Sand Beach graphic novel series, perfect for fans of Gravity Falls, Rickety Stitch, and Fake Blood. Black Sand Beach #4: Where Do Monsters Come From? is due in May 2023.

Black Sand Beach #3: Have You Seen the Darkness?

By Richard Fairgray

Published by Holiday House

RRP: $26.00

Charlotte Fielding

Charlotte Fielding is a writer who lives in Wellington with her son and dog. You can find her talking about books and writing on TikTok, exploring history, art, and culture on Substack, or at girlgotwords.com.