It’s the final instalment of our NZCYA finalist coverage for 2019! Our final category is the Wright Family Foundation Te Kura Pounamu Award for Te Reo Māori. When she’s not busy being a Sapling editor or a bookseller at Little Unity, Briar Lawry is also an enthusiastic akonga i te reo Māori. So for this category, she took matters into her own hands and assessed Te Hīnga Ake A Māui I Te Ika Whenua, Te Haka A Tānerore and Ngā Whetū Matariki I Whānakotia – with some help from her fellow language learners.

Sometimes we can forget that books for young people – simple language, supported by imagery – serve an audience broader than their age demographic. Children’s books have long been an incredible resource for learners of a language, whichever language you may speak and whichever language you may be learning. As such, the audience for this year’s Wright Family Foundation Te Kura Pounamu prize finalists isn’t limited to tamariki at kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa, but to those learning te reo Māori in their adult lives too. Like me, and like so many others.

So with that in mind, I decided to take the books directly to this audience – in this case, my classmates in MĀORI 602 at AUT’s Te Ara Poutama. To paint a picture of us, we are in our second year of formal learning, intermediate learners, and our cohort features folks from many walks of life. We’re predominantly female – so are the finalist authors, for that matter – but we range in age from ‘standard’ students (your typical fresh-out-of-high-school folks) to grandmothers. A large number of the class have Māori whakapapa, but not all, though we are all committed to playing our part in uplifting te reo and te ao Māori, tangata whenua and tauiwi alike.

Some of my fellow akonga aren’t yet connoisseurs of pukapuka pikitia. But when I pitched the idea of chatting to them about these finalists and their potential as learning resources for us, one classmate, Angie, noted that she’d bought some for the same purpose – to expand her language learning beyond want we are exposed to in the classroom.

…she’d bought [Māori picture books] for the same purpose – to expand her language learning beyond want we are exposed to in the classroom.

The finalist books are all very different, but certain threads run between them. For one thing, they were all originally written in English, then translated into Māori. That’s hardly unusual – the vast majority of Māori language picture books available started life in English, before being passed to expert translators to capture the spirit of the story in a way that also works with the nuances of te reo Māori.

The other most notable thread – something noted by several classmates without prompting – was that they all tell Māori stories, rooted in tradition in one way or another, however different they may be. You can’t paint them with the same brush. And to us specifically, the other connection between the three was their complexity, with one classmate casting her eye over them all in quick succession and wailing that they all seemed terribly advanced. But we continued on our examination nonetheless.

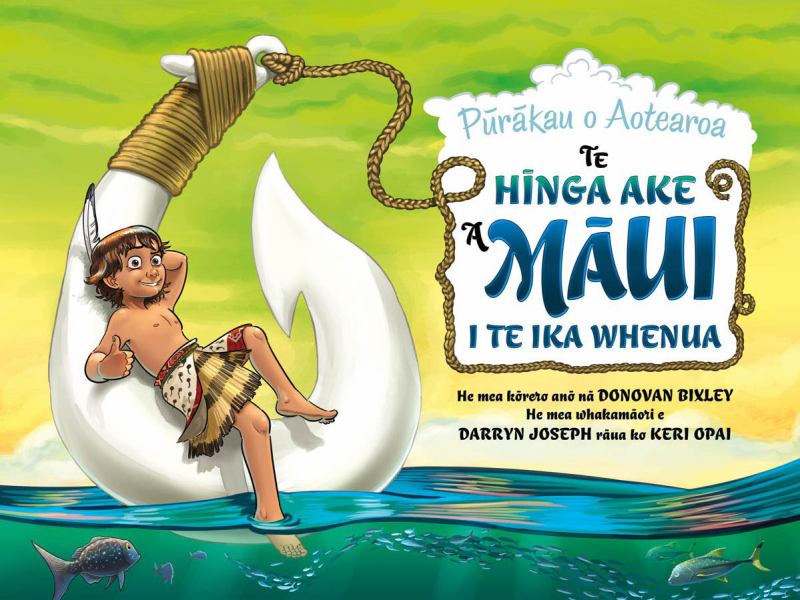

Te Hīnga Ake A Maui I Te Ika Whenua (How Maui Fished Up The North Island) is written – specifically and respectfully phrased as ‘kōrero anō’ and ‘retold’ respectively – and illustrated by Donovan Bixley, with the translation by Darryn Joseph and Keri Opai. It’s the first in a planned series, Tales of Aotearoa or Pūrākau o Aotearoa. This is a story that we were already familiar with, which helped significantly in our comprehension.

Donovan’s series seems like it’s going to have a lot of crossover with the pūrākau covered by Peter Gossage’s beloved books, but we had no sense of usurping. The underlying stories may be the same, but the portrayal is very different – Angie remarked that this felt like a Disneyfied version. It’s a fair observation, one that can be taken as compliment or criticism. But for the core audience of kids, the bright colours, emotive faces and attention to detail will all be selling points, even if they aren’t perhaps as ‘stylish’ as some other offerings out there.

Illustrations are a massive part of comprehension for language learners, and this book was probably the most useful in that regard: between our level of comprehension, prior knowledge of the story, reading between the lines and looking at the imagery, this was definitely the book we were able to understand best. With no other readily available te reo Māori versions of Maui picture books, Te Hīnga Ake A Maui I Te Ika Whenua is a fun, colourful and comprehensible telling of the tale to add to a home library, and we can only hope that the Pūrākau o Aotearoa series grows and expands swiftly.

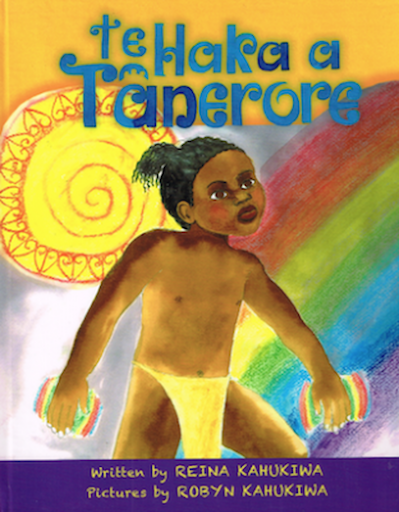

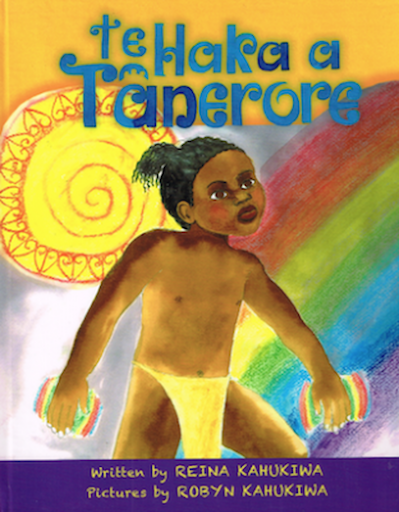

Te Haka A Tānerore (The Haka of Tānerore), by Reina Kahukiwa, was the book of the three that I personally was most drawn to, if we’re judging by cover alone. Which one shouldn’t do, of course, but the reality that it’s always going to be a factor. The beautiful illustrations by Robyn Kahukiwa are eye-catching and evocative as they always are, and you know precisely what kind of a story you’re going to be in for, even before reading the title. On the topic of the title – and that of Te Hīnga Ake A Māui I Te Ika Whenua too, for that matter – we also studiously assessed the use of the ‘a’ rather than ‘o’ for the possessive ‘of’, in line with our most recent class. Everything is a learning opportunity.

The beautiful illustrations by Robyn Kahukiwa are eye-catching and evocative as they always are, and you know precisely what kind of a story you’re going to be in for, even before reading the title.

This story is a core part of Māori history, but it’s not so well known as the exploits of Maui, or the stories of Rona or Pania who had their tales immortalised in Gossage’s work of the 1980s. So while some of us were familiar with the pūrākau in a broad sense, we didn’t have the blow by blow understanding that we had for Donovan Bixley’s book.

As such, it provided the most challenging read. There’s a fair chunk of text on each page, and before going in with our dictionaries open (or our fingers flying frantically on the Māori Dictionary app), there was a fair amount lost in translation. But that was on us, and our level of language, rather than the story itself or its translation, which reads beautifully aloud. The painted illustrations are absolutely magical, capturing moments from the story in Robyn Kahukiwa’s inimitable style. They don’t do as much storytelling heavy-lifting as those in Donovan Bixley’s book, but once we established what each spread’s text said, the significance of the related image was quickly made clear.

On a practical note, it’s also worth noting that Te Haka A Tānerore is very well produced. It’s a hardback, with full-colour glossy pages that are nice and sturdy, giving it an edge over more common, flimsier offerings when it comes to standing up to preschooler enthusiasm.

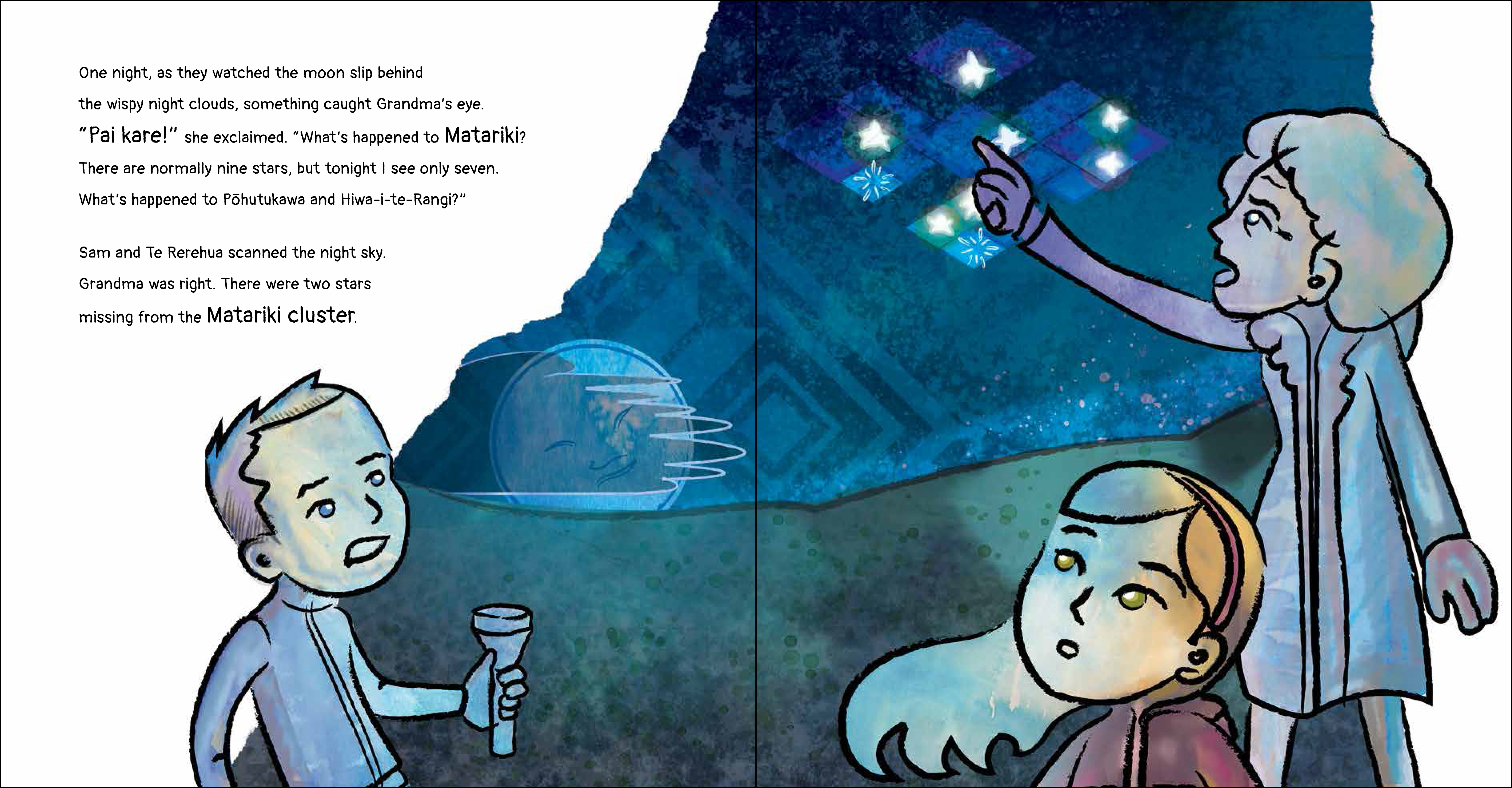

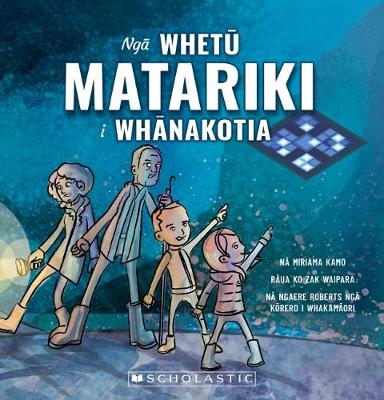

Ngā Whetū Matariki I Whānakotia (The Stolen Stars of Matariki) could have posed the biggest challenge for us as readers since it doesn’t draw from existing pūrākau in the same way as both the other finalist titles. While it’s centred around the constellation of Matariki, one of an increasing number of picture books that does so, it doesn’t call upon a specific tale from the past. Instead, it incorporates a contemporary family with mischievous patupaiarehe and the idea that the Matariki constellation has, in fact, nine stars, not seven.

This book has been translated by Ngaere Roberts, who is prolific in her translation work, particularly for Scholastic. As with all of her work, there is clarity and simplicity in her use of te reo Māori, and despite having the most unfamiliar storyline, it was the most accessible for us to read. One classmate, Jo, noted that the decision to use simple black on white text made it a lot easier to absorb the writing, since the act of physically reading it was easier, which makes perfect sense. Jo also commended the book’s illustration, with its muted colour palette and watercolour style, although she did note that the artwork inside appealed more than the image chosen for the cover.

Scholastic has been doing a wonderful job with their commitment to te reo Māori publishing, with a large percentage of new New Zealand-based publishing being simultaneously released with te reo Pākehā and te reo Māori editions. There’s also an inherent acknowledgement that not all folks reading these books will be fluent speakers themselves – and as such, there’s a comprehensive glossary inside the back cover to refer to. It’s a major help for language learners like ourselves, but it’s easy to see how it would benefit parents and kids too. If a preschool child is in an immersion environment such as kōhanga reo, but their parents aren’t confident speakers, the glossary allows them to get a better understanding of what they are reading to their child – and in turn, it will allow them to read in a lively, active manner.

In short, in our collective mind, all three books are worthy contenders for the Te Kura Pounamu prize. Some folks commented on the ‘authenticity’ of the illustrations in Te Haka A Tānerore as a selling point above the others, while another classmate questioned whether that authenticity was truly a factor that would make or break a story. Our shared preexisting understanding of Maui’s stories made Te Hīnga Ake A Māui I Te Ika Whenua popular with some people. The fresh contemporary tale of Ngā Whetū Matariki I Whānakotia and its accessible language made that book a hit with others. There’s no wrong winner – so bring on the ceremony!

Karawhiua, e hoa mā! Get out there and challenge yourself to pānui ngā pukapuka i te reo Māori – even if they are targeted at kids. And ngā mihi to Angie and Jo and all others who shared their whakaaro with me for this article. is a great way to start some significant dining table conversations throughout Aotearoa.

TE HīNGA AKE A MĀUI I TE IKA WHENUA

By Donovan Bixley

Nā Darryn Joseph rāua ko Keri Opai ngā kōrero i whakamāori

Published by Upstart Press

RRP: $19.99

TE HAKA A TāNERORE

By Reina Kahukiwa & Robyn Kahukiwa

Nā Kiwa Hammond ngā kōrero i whakamāori.

Published by Mauri Tu

RRP: $30.00

NGā WHETū MATARIKI I WHāNAKOTIA

By Miriama Kamo & Zac Waipara

Nā Ngaere Roberts ngā kōrero i whakamāori.

Published by Scholastic NZ

RRP: $18.99

E noho ana au kei roto i te taumarumaru o Maungakiekie, ā, e noho ana au ki ngā tahataha o te Tīkapa Moana.

Ko Ngāti Pākehā tōku iwi. I whāngaia ōku tūpuna e te whenua o Te Whānganui-a-Tara, me Ahuriri, me Tāmaki Makaurau.

Briar Lawry is an English teacher and writer from Tāmaki Makaurau. She worked in bookshops for years, most notably Little Unity, and judged the NZCYA Awards in 2020. She was also one of the editors of The Sapling between 2019 and 2023.