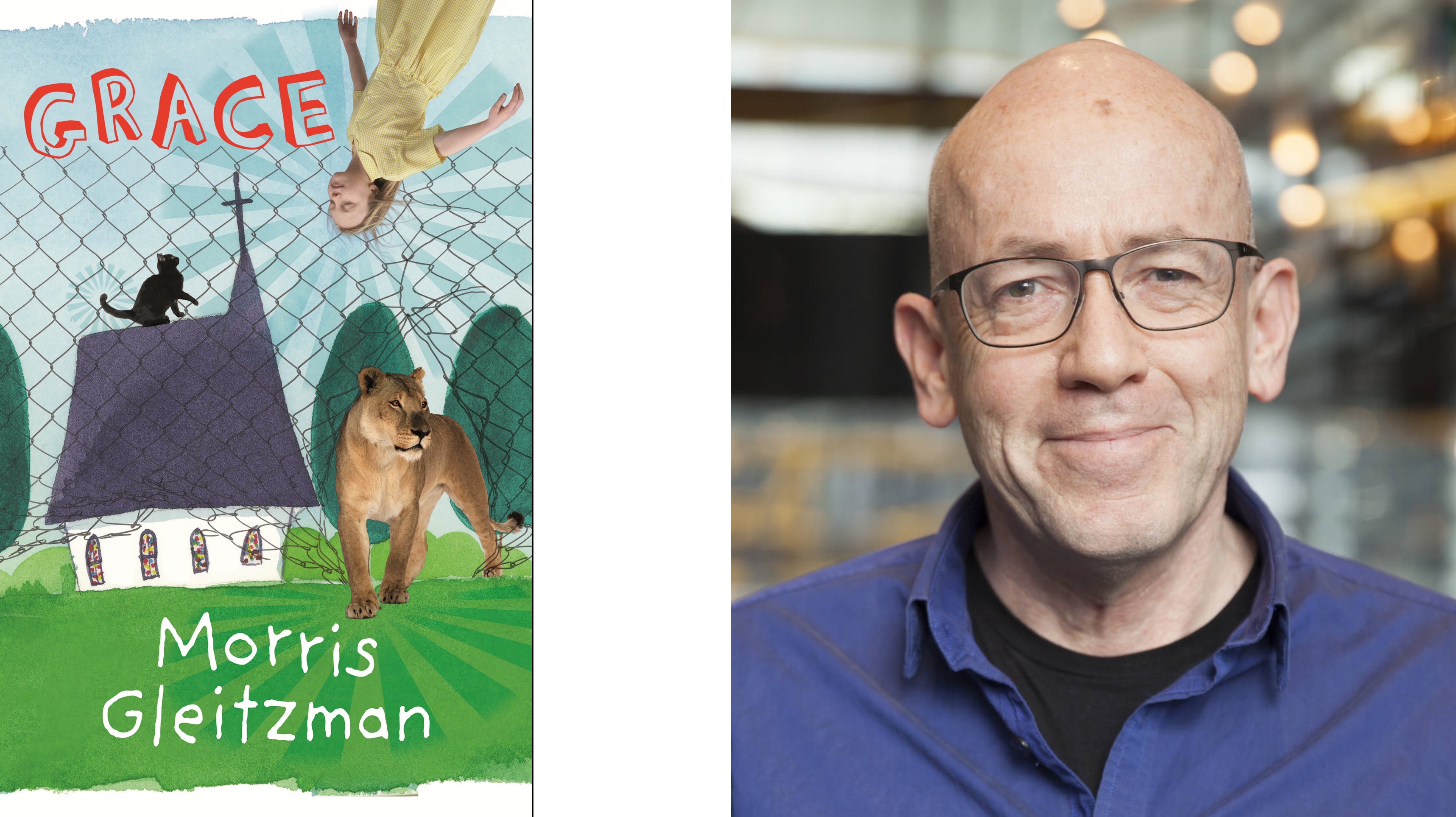

Morris Gleitzman, acclaimed author of Toad Rage and many other books, is the 2018–19 Australian Children’s Laureate – the nation’s ambassador for children’s literature. The role is keeping him intensely busy, but Johanna Knox managed to speak with him by phone while he was caught in traffic between engagements. Their conversation connects dots between the climate crisis, plot structure, public speaking, and the value of the Laureateship. Plus it definitively (we think!) answers the question: Should Aotearoa New Zealand have a Children’s Laureate?

When Australian school students took to the streets on climate strikes last year, Morris Gleitzman backed them publicly. ‘It was something I personally wanted to support,’ he tells me, ‘and something I thought the Children’s Laureate should be seen supporting. Some might say, “Put your Laureate hat back on, and stay where you’re meant to be.” But for me, it directly connects to what I’m talking about as Laureate.’

Each Australian Children’s Laureate chooses a theme for their Laureateship. Gleitzman’s is Stories Make Us – Stories Create Our Future.

‘When I listen to young people talk about their futures, I’m aware that they’ll face bigger and more difficult challenges on a global level than any human generation before. So adults have a responsibility to equip them, as much as we can, with attributes and ways of thinking that will maximise their opportunities to deal with these challenges.

‘Stories equip young people to become fearless, resilient problem-solvers, or battlers with problems. And those young people around the world – who in some cases took risks to join the climate strikes – I think that’s the perfect example of the sort of preparedness to stand up be counted that will be needed. Entire future generations will need to become involved in whatever problem-mitigating and problem-solving strategies they can evolve.’

‘Stories equip young people to become fearless, resilient problem-solvers, or battlers with problems.’

He describes the way books help: ‘A typical story for young people has a young protagonist facing a huge problem in their life. And if it’s a problem bigger and more confronting than any they’ve faced before, that’s a particularly interesting story. It needs to be a problem so big and urgent that the human tendency to try and sidestep, or put our head under the pillow, or blame somebody else … the young character can’t do that.

‘So, immediately, the problem is pushing them beyond the previous boundaries of what they’ve been capable of and comfortable with, and they need to develop in specific ways: to develop the capacity to think bravely and honestly about themselves, their place in the world, what relationship they have with that problem, and whether they’re even contributing in some ways to the problem.’

For Gleitzman’s protagonists, researching the problem is often vital – gathering information and learning how to sift through it. ‘And once they fully understand the problem, they need to think about whether they can make a good job of either solving or surviving it on their own.

For Gleitzman’s protagonists, researching the problem is often vital – gathering information and learning how to sift through it.

‘Usually, in my stories, they won’t, because it’s a huge problem. So they’ll need to form alliances or friendships with people who may not be people they’d normally do that with. It’s developing their capacity to open their minds to other types of people, or other relationship possibilities. And that invariably involves developing empathy – one of the most valuable life skills in any context.

‘Finally, they’re ready to apply a strategy to their problem, and that’s when they discover that, because they’re a character in long-form fiction and it’s only page 36, there’s no way their strategy can succeed, because their author is contracted to write 260 pages!

‘So they’ll fail, and have to develop the capacity to come out of that pit of feeling crushed and shamed, to look bravely at the failure and see what can be learned from it to develop another problem solving strategy.

‘The process will continue through three or four different strategies, or the development of a previous one, to a point

where, at the allotted time, they either solve or survive the problem.’

He adds, ‘In my books, they often don’t completely solve the problem. This is probably my single most important rule of writing fiction: As long as the character is better off at the end of the story than they were at the beginning, in terms of how they feel about themselves and their place in the world, I don’t mind if they’ve got years of struggle ahead. Many problems are too big to be solved even in one lifetime.

‘So all those developmental points are life skills. Reading stories is not the only way we experience those development opportunities, but it’s one. And if you’re a lucky young person who gets to go on that story journey hundreds of times in your childhood years, connecting emotionally each time with the main character, walking in their shoes, sharing their inner worlds, then that developmental process can’t help being internalised. That’s why I maintain stories are one of the most useful and valuable ways of helping equip young people for challenges.’

‘That’s why I maintain stories are one of the most useful and valuable ways of helping equip young people for challenges.’

***

Before becoming Children’s Laureate, Gleitzman devoted most of his speaking time to promoting his own work – a necessity in the book industry. However, his readership had become secure enough that he was considering taking a break from self-promotion. Instead, ‘maybe it was time to talk about these larger ideas to do with why one writes stories for young people. And just as I was thinking I’m going to use my public voice to start or continue some of these conversations, along comes the invitation to be Laureate.’

Like the Australian Children’s Laureates before him, he has seized the chance to use that voice widely. ‘Speaking to adults – from parents through to policymakers and purse string holders – I’m finding that, often, what I am is a reminder. I’m not telling adults anything they don’t already know. I’m just reminding them to not let such an important thing as children’s reading slip down their list of priorities.’

‘I’m not telling adults anything they don’t already know. I’m just reminding them to not let such an important thing as children’s reading slip down their list of priorities.’

And they listen. ‘Perhaps it shouldn’t be the case, but people are still impressed by a slightly grandiose title. People pay attention. The media pays attention. I spoke to a group of parliamentarians in Parliament House last year, and I thought to myself, a lot of them knew my work, had kids or grandkids who read my books, but I wouldn’t be standing here if I didn’t have that slightly grandiose title.’

This, of course, is exactly what the Children’s Laureateship, in Australia and other countries around the world, is intended to achieve. ‘In a busy world with lots of claims on people’s time and resources, it’s useful to have somebody who is an advocate, a spokesperson for that community of people who feel that reading and stories make a huge contribution to the lives of young people, and that our lives are poorer if young people aren’t given the maximum opportunity to have a rich and varied reading diet.’

Note the word ‘community’. Gleitzman says the Laureateship should not just be about ‘an individual doing a series of things over a two-year period. It should be a community, for which, every two years, there’s a new Laureate who is the public face and a spokesperson. The Australian Laureateship grew out of a group of people who came together from many organisations and professional areas, and who cared about the importance of young people’s reading. They looked at other countries and saw what a Children’s Laureate was, and they decided we would have one. They applied for funding and they organised the Board.’

‘The Australian Laureateship grew out of a group of people who came together from many organisations and professional areas, and who cared about the importance of young people’s reading.’

The past Australian Laureates and their work remain important to the community, and each Laureate, as well as bringing their own interests and initiatives to the role, carries forward the legacies of their predecessors. Gleitzman, for example, continues the fight to save school libraries begun by the 2016–17 Laureate, Leigh Hobbs.

In other countries with Children’s Laureates, a similar sense of community exists, and furthermore, Children’s Laureates from around the world are networking with each other in the hopes of building global solidarity. The Bologna Children’s Book Fair now runs an international Laureate’s Summit biennially.

The Children’s Laureate movement began in the UK: Quentin Blake held the first Laureateship in 1999. Australia and the US came on board almost a decade later, then Ireland, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Has Gleitzman heard, I naively ask, that there is a movement to create a Children’s Laureateship here in New Zealand?

‘I have! At the Summit, we were all remarking that it would be wonderful for New Zealand to join our gang. New Zealand has a wonderful children’s book culture, wonderful writers, great support people. I’ve met many wonderful teachers and librarians over the years there, and it strikes me that it’s a country absolutely ripe to have a Children’s Laureate.’

‘I’ve met many wonderful teachers and librarians over the years [in New Zealand], and it strikes me that it’s a country absolutely ripe to have a Children’s Laureate.’

***

In Australia, as in other countries, the Laureateships are two years long, for which Gleitzman is grateful. ‘It wasn’t till the end of the first year that I really started to get a sense of a couple of the projects I want to do that are specifically to do with my own take on the role. I’m going to be pretty busy over these last months.’

One project involves public speaking workshops for young people, because while books may equip readers with new ways of thinking, he also wants to help thoughtful young people express those thoughts persuasively.

‘When I realised part of the “author” job description was to stand in front of large numbers of strangers and talk at them, I found it a terrifying proposition. But you have to do it, so I learned how. Now I enjoy it, and I think I do it pretty well. It can be learned.

‘So later this year, I’m working with a group from the Queensland Performing Arts Centre. We’ll create a workshop helping young people develop the confidence, abilities and strategies to become local leaders. My goal is to do it in such a way that we can send a blueprint to every school in Australia, a resource pack, so teachers can work through it with young people. It doesn’t have anything directly to do with reading and literature, but to me it’s at the pointy end of this notion of equipping young people via their reading.

‘For a healthy functioning society, we don’t want the power and the decision-making process to be just in the hands of the people who are born feeling feel confident and able as public voices.’

***

If there’s one thing that the Children’s Laureateship movement highlights, perhaps it’s that powerful, illuminating stories don’t exist as inert entities. They’re more like networks of filaments, reaching into our lives and communities in any ways we let them. The more we allow new ideas, conversations and enterprises to surround these stories and flow through them, the more incandescent they become. And this lighting-up process is something that everyone who cares about children’s literature can take part in – whether they’re having discussions in the public arena or snuggled up on the couch with a single child.

Gleitzman says, ‘The more you’re making opportunities for children to read as widely and deeply as possible, the more what they read will expand their view of the world. They’ll come up against aspects of human existence that they haven’t known about, or that they’ll see through different eyes, and they’ll invariably want to have conversations about what they’re discovering.’

‘The more you’re making opportunities for children to read as widely and deeply as possible, the more what they read will expand their view of the world.’

For parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, teachers and librarians, ‘making the time to talk, is, I think, one of the most fruitful investments one can make. It’s about giving young people the opportunity, and signalling to them that you’re open to these conversations, but not in a way that makes it sound as if it’s your agenda.

‘I’ve come to believe that the conversations are in every way as important as the books, the stories, and the reading. And I think that the really lucky young people, and the ones who will be best equipped, are those who’ve not only had a childhood full of reading, but one full of conversation about anything and everything they want to have conversations about.’

Johanna Knox

Johanna Knox is the author of The Fly Papers, A Forager's Treasury, and Guardians of Aotearoa, which was chosen by the NZ Heraldas their 2018 Book of the Year. She was the editor of Forest & Bird's magazine for children, Wild Things, from 2013 to 2016, and currently edits Diabetes Wellnessmagazine, as well as teaching Writing for Children online at Whitireia. She completed an MA in Creative Writing at the IIML last year, and is now studying for a diploma in rongoā Māori at Te Wānanga o Raukawa.