Maurice Gee’s O Trilogy is one of the most enduringly excellent works of Aotearoa literature. Megan Dunn recalls its power.

In the South Island, at the back of an old mineshaft is the entrance to the planet O. There are two ways to get there. You can be forced by a coil of venomous yellow smoke like Susan Ferris. Or if you are lucky, you can get there by ‘Shy’, a small silver plant, a dozen blue flowers just visible in its leaves. It only grows on O. The Woodlanders know where to find it.

I wrote that paragraph over a decade ago for an essay about Maurice Gee’s O trilogy that never made it to print. I’ve wanted to write this love letter to Gee’s trilogy for too long. I first started thinking about the fictional planet of O – and by extension New Zealand – in the mid 2000s, as a thirty-something bookseller, who lived in England, and witnessed firsthand Harry Potter hysteria and the burgeoning Twilight phenomenon. My patriotism was piqued. How did Gee’s O trilogy shape up?

But perhaps I could never answer that question because my memories of home and O had already intertwined; a planet of rolling Colin McCahon hills, all those plains of nothingness, only the land itself. To me Mount Morningstar was an epic frosted peak like Mount Taranaki and when Gee’s exasperating Jimmy Jaspers – a Footrot Flats style curmudgeon – built a shack on O and settled down, it looked exactly like Rita Angus’s painting Cass.

In his memoir Creeks and Kitchens Gee wrote of his O trilogy, ‘I wanted settings New Zealand children would recognise, with New Zealand as the most important place in the world, as it is for the children who live here.’

Gee wrote of his O trilogy, ‘I wanted settings New Zealand children would recognise, with New Zealand as the most important place in the world, as it is for the children who live here.’

Now even Gee’s choice of the word shy strikes me as genius. ‘There is a kind of magic in naming’ he says. So it seems fitting that ‘Shy’ becomes the portal between two worlds, just as shyness is so often what sends young readers on quests into the library to browse its seemingly infinite stacks. I was once that shy girl with my head in a book and that book was The Halfmen of O by Maurice Gee.

O still seems the perfect name for a planet, after all O is the shape of the world. Although as an ex-bookseller the unintended resonance with Pauline Reage’s title The Story of O bugs me. If you’re not familiar, let’s just say Reage’s erotic masterpiece is decidedly French and has a black cover. Which brings me to my point: how do we return to our childhood reading freighted with the knowledge of our adult selves? And do we – can we – ever read with that same feverish belief we had as children again? The same shyness.

And do we – can we – ever read with that same feverish belief we had as children again? The same shyness.

In 1982, I first met Susan Ferris, a dreamy twelve-year-old with a far away look in her green eyes. The unusual birthmark on her inner wrist was just the yin and yang symbol coloured red and gold, but I didn’t know that then. Accompanied by her know-it-all cousin Nicholas Quinn, and Jimmy Jaspers, Susan was transported to planet O. There her quest was to restore the balance between good and evil by placing two halves on the Motherstone. No pressure.

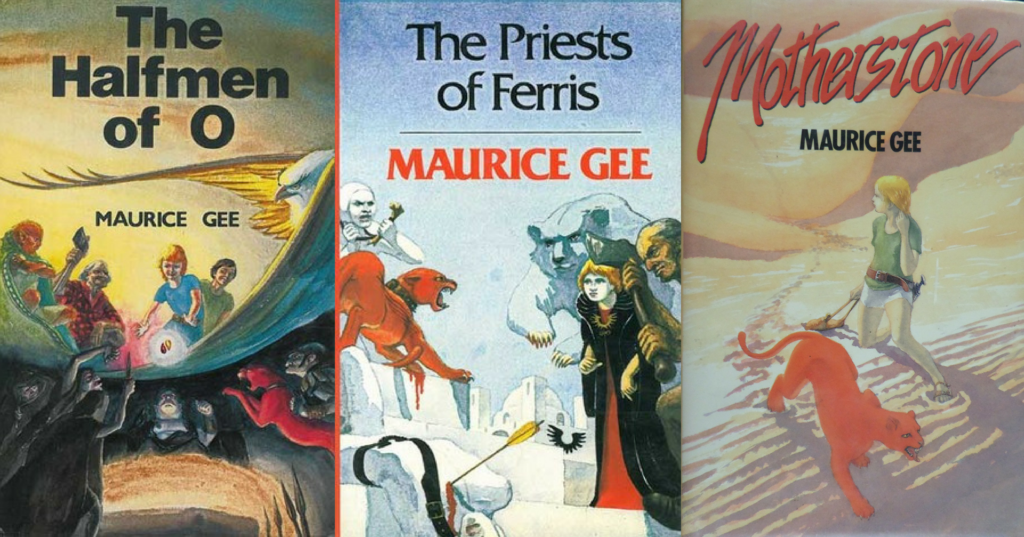

Gee wrote the O trilogy during the 1980s, the decade of Rogernomics and the Rainbow Warrior bombing. Again, from Creeks and Kitchens: ‘There are lessons in those books, if the child readers can find them – about the pollution and degradation of the environment and of natural things, about the danger of nuclear weapons, about the abuse of political power.’ The 80s was also the decade of the Star Wars franchise. I still remember an early cover for The Halfmen of O, in which Gee’s evil overlord Otis Claw, the Darksoul, looked endearingly similar to Jabba the Hut. (By the way, Penguin, please bring back the original covers illustrated by Gary Hebley; the current photographic ones are totally bland!) And I always imagined the indigenous woodlanders of O, Brand and Breeze, as Ewoks, only with finer fur. All the folk on the planet, the Woodlanders, Birdfolk, Seafolk and the Stonefolk live in harmony with nature. It’s humankind that causes the problems, as per usual.

At the start of the trilogy O is ruled by the Halfmen or ‘Halfies’ who see only grey out of their pink eyes. Whereas JK Rowling has magic and Muggles and Halfbloods, Gee has only ‘Halfies’ because on O humanity has been split asunder. And the Halfies are all bad. ‘I know your tricks, Mixie,’ says Odo Cling, the second in command to Otis Claw. Susan is still a ‘mixie’ – a mixture of good and bad, right and wrong, of all the contradictions that make us human. I used to say ‘I know your tricks, Mixie,’ to my ex-husband, an Irishman who’d never been to O and who never came to New Zealand with me either.

Whereas JK Rowling has magic and Muggles and Halfbloods, Gee has only ‘Halfies’ because on O humanity has been split asunder. And the Halfies are all bad.

Was Voldemort ever as frightening as Gee’s vision of a grey planet? When Susan arrived on O she saw a landscape with grass the colour of tin and worst of all ‘…most hideous of all, burning without colour overhead, a huge black sun set up there like an iron hot-plate in the sky… Susan screamed. She looked at herself. Her skin was grey, her nails gleamed like chips of polished stone. She grabbed a handful of hair and pulled it round. It was grey and dead as an old woman’s hair. She cried out with horror and disbelief…’

Fair enough, she is only twelve.

Gee is the Hemingway of children’s adventure/fantasy writing. His sentences are short and sharp but they hit the spot. He doesn’t liberally use speech tags like ‘chortle’ (Rowling take note) and he doesn’t stop and supply the lyrics to all the Woodlanders’ songs (Tolkien, I’m looking at you). Nor do you ever have to wonder why everyone is speaking English on O or get embroiled in the syntax of the language of Seafolk (talking seals that eat seaweed when their voices get hoarse; deal with it.)

Gee is the Hemingway of children’s adventure/fantasy writing.

In The Priests of Ferris, the second book in the series, published in 1984, Susan returns to O only to discover a false religion has sprung up in her name. The Priests are ‘human skeletons’, dressed in white leather suits that cover everything except their faces. At night they turn the suits inside out and are dressed in black. Except for their faces. Their faces remain white. Around their necks are ‘Ferris bones’, the bones of heretics. Amen.

I really ‘got’ The Priests of Ferris. Gee described the High Priest as a ‘headmaster’, a paper pusher, behind a desk. I didn’t think our headmaster believed in our school motto either. I also got the way Susan’s epic hang-glider ride in The Halfmen of O had become distorted over time. The Priests of Ferris believed she had literally ‘flown’ and consequently in the novel young girls were thrown from Deven’s Leap every year. If they believe, they will fly. But none do. After I finished The Priests of Ferris, I watched my Grandmother click her rosary beads together with greater suspicion. ‘I don’t believe in God anymore,’ I told my Mum. But I still believed in O.

So much so, that I bought the third and final book in the series, Motherstone (1985), as a birthday present for my friend Fiona. Her parents ran a motel in Rotorua and she was conceived on site in a beanbag (and proud of it.) When I picture handing a gift-wrapped copy of Motherstone to her, she is seated in a beanbag, her long nails reaching out for the present – obviously a book – that only one of us really wants to read. I guess Gee could have provided a bit more steam.

Perhaps a post-colonial read of the O trilogy might also prove problematic today. Gee’s presentation of the tribe of ‘Hotlanders’ at the end of the trilogy could be construed as culturally insensitive. ‘Their speed seemed impossible, their long thin arms, their fleshless arms, jointed in a way that seemed inhuman…Their shaven skulls gleamed like plastic bowls.’ However, overall I think Gee’s politics are pretty sound. I know my worldview is still essentially the same as when I first encountered O: the balance of humanity is of out of whack, government is corrupt, our greatest evils are enacted in the name of faith. Maybe we do just need to wipe the slate clean and start again? For that’s pretty much the solution Gee proposes for humanity.

…my worldview is still essentially the same as when I first encountered O: the balance of humanity is of out of whack, government is corrupt, our greatest evils are enacted in the name of faith. Maybe we do just need to wipe the slate clean and start again?

I don’t want to risk any more plot spoilers, so let me just say that Motherstone is my favourite O book for two reasons: Greely and Slarda. Their names still remind me phonetically of Greedy and Larder. These women pursue Susan across the desert with the single-mindedness of hunters after prey. They aim to kill her. I was surprised to see such savageness attributed to women characters in a novel. I spent much of the 80s followed home from school by pairs of savage girls except mine weren’t armed with crossbows. Just sharp tongues.

Gee’s portrait of the Hotlands, a hitherto unchartered area of O, also spoke deeply to someone raised in Rotorua. ‘Mud lakes boiled like porridge pots. Cliffs steamed and geysers burst from mounds and roared in jets and sprays and feathers high into the air. Around them the bush was warped and mineral crusted.’

My inheritance from O is simple: the planet has a pulse. Gee’s gift to children’s literature is the characterisation of a world that it is worth saving, in and of itself. For itself.

My inheritance from O is simple: the planet has a pulse.

It’s also really cool when Susan befriends the Bloodcat, ‘Thief’, in Motherstone. I once tried to paint a watercolour of ‘Thief’ in fourth form art class, but my teacher said I had to use black paint because on earth leopards are black. But on O – that’s another story.

On my father’s bookshelf I once discovered a deep burgundy spine that also bore the name Maurice Gee. I pulled out the book and inspected its title, Plumb. I read the blurb. My mind was sent momentarily reeling. How could the same author as the O trilogy write this boring book for adults? Plumb – recently voted New Zealand’s greatest novel of the past fifty years – just felt heavy in my hand. I’d better go and read it.

Megan Dunn

Megan Dunn lives in Wellington where she Skypes mermaids and writes about contemporary New Zealand art. Her first book, Tinderbox, is about her attempt to rewrite Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, the demise of Borders bookstores and Julie Christie's haircut. But not necessarily in that order.