Editor Hannah Marshall heads back in time in Tessa Duder’s newest YA novel, The Sparrow. Hannah puts some serious questions to Tessa, getting great insights into researching and writing historical fiction.

Hannah Marshall: You’re a veteran of New Zealand literature. Does the process of writing novels get any easier, and do ideas come easily to you?

Tessa Duder: For me ‘ideas’ (i.e. the compulsion to write about a swimmer [Alex], or a young actress [Tiggie Thompson]) have come relatively easily, but once I get going it’s the characters who drive the plot, according to their personalities and motivations. Writing The Sparrow was in one way different from those earlier series; this time I had much more editorial input from two wonderful editors—for which I was very grateful and the novel much the better for it. So not ‘easier’ as such, rather, more exacting and challenging.

H: I had never known about the British convict women sent to Australia, or even heard of the Cascades Female Factory before reading The Sparrow. What sparked your interest in writing about this topic?

T: As a fourth-generation Kiwi, I’ve long been interested in the 19th-century diaspora from Britain and Europe, whether as convicts or emigrants; all my great-grandparents from England, France and Italy endured those terrible long voyages under sail. I have my English maternal great-grandfather’s very detailed shipboard journal.

Finding that the Platina, present in the Waitematā in 1840, had earlier been a convict ship, I wanted to know more about the 113 females transported in 1837 and further, about their destination, the Cascades Female Factory in Hobart. It was a prison but called a Factory because the inmates did the town’s laundry and worked as seamstresses or servants. From there Harriet’s convict backstory just evolved. I’m grateful to Penguin editor Harriet Allan for encouraging me to make more of her experiences in Newgate Prison, as a passenger in the dreadful conditions of a 19th-century ship and as a prisoner for three grim years at Cascades. Two recent books by Australian authors on female convicts were invaluable.

H: What are the challenges of writing historical fiction compared with writing a contemporary story?

T: Your major challenge is to have the novel ‘ring true,’ to convince the reader that it’s authentic to its time, the setting, the characters, their expectations and reactions to circumstances, the language they would have used, the modes of transport, their dress and manners. Of course, these also apply to contemporary fiction, but the historical novelist must rely on written records and such images as exist, and having done sufficient research, let loose their imagination. Have fun, certainly! While also, crucially, not falling into the trap of seeing events through a 21st-century lens or overloading your narrative with too much of your hard-earned research.

H: What kinds of research did you do before writing?

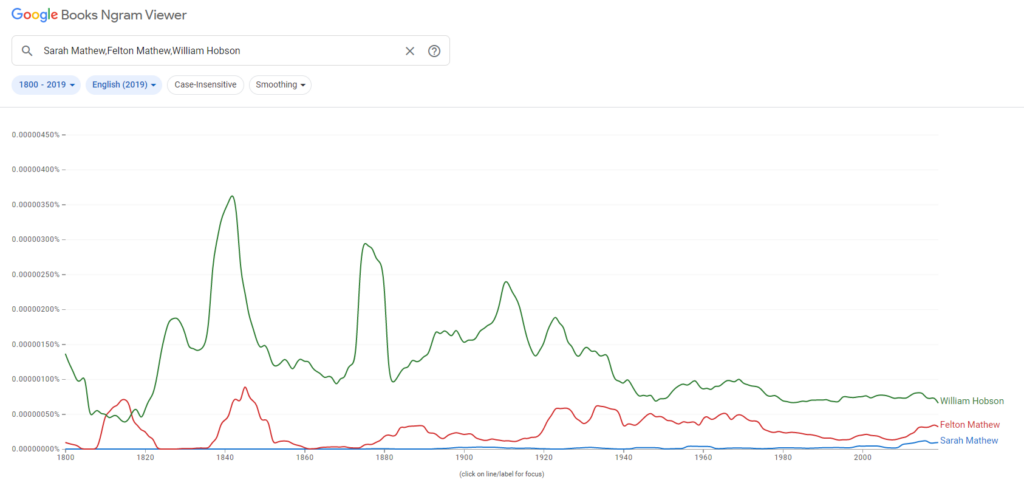

T: A great deal of reading! Histories of Auckland and the first settlers, biographies of the historic figures appearing, maritime history, convict history. Adding to what I already knew from researching my 2015 book about the early Auckland diarist, Sarah Mathew, I scoured websites like the Te Ara Encyclopaedia, Early New Zealand Books (ENZB) and Google NGram (a marvellous tool that shows in graph format the general usage of any English word over the past two centuries). Multiple websites on early Hobart and the Cascades prison. For the sections set in rural Sussex, I drew on my own memories of living in southern England in the 1960s and a deal of website browsing.

H: Most of the characters in the novel are fictional, but there are a few famous historical figures featured—including William Hobson and Sarah and Felton Mathew. How do you incorporate real people into fiction, and was it a difficult process?

T: Not difficult at all, because I stuck closely to the known historical record of early Auckland. But to have my fictional characters meet and talk with and about them required some insight into what they were like as people in everyday life, to present them as authentic and real personalities. I hunted down personal references to them by contemporary writers. The formal naval captain, Governor Hobson, for instance, is described by several commentators as a fusspot, used to his orders being promptly obeyed; today I think we’d call him a micro-manager or even a control freak. My servant girl Tillie finds him demanding, but also observes the ill-health which killed him two years later, only 49.

H: Naturally, writing about colonisation from a Pākehā perspective means confronting some uncomfortable truths about our country’s past. How did you decide in what way you would portray sensitive historical events and the attitudes of settler society at the time?

T: The Sparrow is Harriet’s story, told in the first person: what she sees and hears, the impressions she forms and how she reacts to events are all uniquely hers. So it’s told from the perspective of a spirited, sharp-eyed girl, not an authorial one. Holding onto the liberal values instilled by her father, and with her own strong sense of justice, Harriet is openly dismayed at the settlers’ ungrateful and patronising (today we’d say racist) attitude towards local Māori who come to build them huts and supply much-needed food and firewood; her outspokenness costs her dearly.

Interestingly, one reviewer has noted, in the context negatively, that ‘this is the story of colonists and the voices of Māori are noticeably absent’, but I would argue that there is a significant Māori presence, as observed by Harriet and that how they feature in the narrative of those first six months of Auckland is consistent with the time, place and circumstances described.

Teens are as diverse and adventurous in their reading as any, and many will always look beyond ‘relevance’ to simply experience the enjoyment of ‘a good read’

H: How do you make historical fiction relevant to modern readers?

T: I don’t believe it’s an author’s job to strive to make historical fiction—or any genre, for that matter—specifically ‘relevant’ for today’s teenage readers. A good story is a good story, whether set in ancient Greece or Tudor England, pre-European Aotearoa or the early 21st century.

With the rise of young adult fiction in the 1980s there was a perceived demand for ‘issue’ books dealing with teenagers’ ‘real’ lives: involving drugs, family conflict, sexual worries etcetera. Away with fantasy, adventure and history, read about your lives, your problems! That strikes me as highly patronising, restrictive and damaging. Teens are as diverse and adventurous in their reading as any, and many will always look beyond ‘relevance’ to simply experience the enjoyment of ‘a good read.’

H: Why do you think this story is important for young people?

T: Harriet’s story fleshes out existing histories of the female convicts’ transportation to Australia, the prisons of 19th century Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) and Auckland in its early years as the capital. Just as Mary Renault’s novels brought alive for me the world of ancient Greece, or Hilary Mantel’s marvellous trilogy did the same for Tudor England, or do the many novels about 19th century New Zealand by Fiona Kidman, Jenny Pattrick, Whiti Hereaka, Deborah Challinor et al.

With the new emphasis on history throughout our school system, historical fiction can and should play an important role in deepening students’ awareness of the past, adding colour, vitality and human interest to the accounts of how their ancestors struggled and survived. And Auckland’s unusual, even unique, founding story is well worth re-telling.

Literature more inclusive? Happily, yes, but there’s also been an increased inclination, especially in USA, towards parents and institutions banning anything remotely risky or—I’d say—real.

H: One of my favourite things about this book was its unapologetic portrayal of topics like periods and sexual violence—topics that appear far too infrequently in stories and are often considered taboo. Have you ever faced a struggle to write about these topics, and do you think literature has become more inclusive in this regard?

T: Writing frankly about things like periods or sexual violence has never been a problem for me, mostly, I think, because including them has always risen from within the story, consistent with the characters’ situations and actions. For example, Alex getting her period the night before her big Olympic race, yet another complication for her hopes of swimming well. (This in my 1990 third novel about Alex apparently horrified a well-known veteran Kiwi author, old-school male, who thought it ‘totally inappropriate for young readers’.) Or Harry/Harriet in The Sparrow being assaulted in her hammock by a sailor—we know such things happened in the cramped mess decks of 19th-century sailing ships.

Literature more inclusive? Happily, yes, but there’s also been an increased inclination, especially in the USA, towards parents and institutions banning anything remotely risky or—I’d say—real.

H: If Harriet were around now, what would she think about New Zealand today?

T: She’d be overwhelmed by modern Auckland. The three bays and Point Britomart headland where she walked daily have disappeared under reclamations, roads and huge buildings, though she’d note the names of two bays have survived. Houses, high buildings and trees on harbour’s slopes where once there was only bracken; on Queen Street, look at those laughing girls wearing next to nothing! Cars, buses, container ships, helicopters, cell phones: things of wonder!

But she’d be horrified hearing about how Māori had fared in the years since 1840. How they’d lost their lands, fought wars again the Pākehā, come close to dying out, been patronised and abused. As the adult she grew to be, a teacher fluent in te reo and fighter for social justice, she’d be right behind current moves to restore Māori mana and influence.

Hannah Marshall is a reader, writer, and advocate for New Zealand books from Wellington. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Media Studies from Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, and she is currently doing her Master of Arts in Creative Writing at VUW's International Institute of Modern Letters. Her debut YA novel, It's a Bit More Complicated Than That, is being published by Allen & Unwin in 2025.