Today we are delighted to share some stellar reviews from writer and public servant Tihema Baker, featuring three teen-friendly(ish) titles from different blokes of letters, mixing fiction with reality, Pākehā and Māori worlds, and single voices with many. Read on, and you might just find something for the reluctant 15-year-old boy in your life.

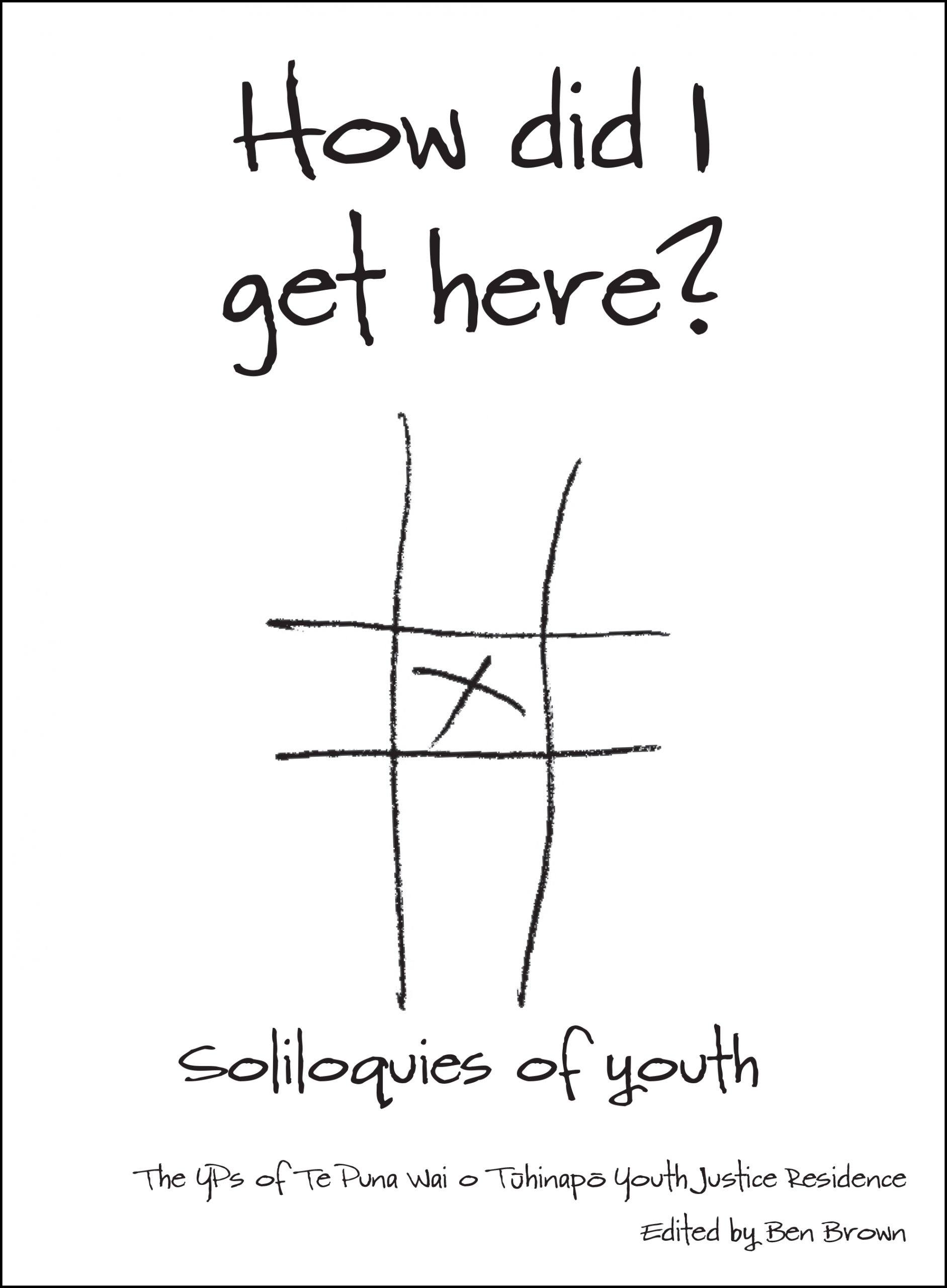

How did I get here? Soliloquies of Youth by The YPs of Te Puna Wai o Tūhinapō Youth Justice Residence and edited by Ben Brown (The Cuba Press)

I once visited a Corrections facility described to me as a ‘halfway house’ for work. It was for young male violent offenders who had recently been released from prison, seeking rehabilitation before reintegrating into society. The experience has stayed with me for what I learned from the young, mostly Māori men there, for the small insight I got into their realities that were worlds apart from my own. How did I get here? is a collection of poetry written by 28 young men living in Te Puna Wai o Tūhinapō, the Oranga Tamariki youth justice residence next door to Rolleston Prison, and reading it was a similar experience to that ‘halfway house’ visit, only deeper and more profound.

The collection was put together by poet Ben Brown of Waikato-Tainui, who took a box of biros, an A4 ream of paper and a question to these young men: ‘How did you get here?’ The poems and illustrations that compose this collection are the answers to that question, together creating a window into a world utterly unlike the one most of us are familiar with. The composition of the book itself is as much a representation of this idea as the words it contains; even the colours are inverted, white text on a black page. Or perhaps the book is not so much a window but a mirror, reflecting back at us the other side of the society and system we inhabit.

Or perhaps the book is not so much a window but a mirror, reflecting back at us the other side of the society and system we inhabit.

This theme – the ‘system’ – is a common one, often referenced or critiqued. Even the concept of system itself is explored, dissecting what it means to be part of a system and what a system’s output is supposed to be. There’s a real self-awareness throughout, a deep understanding of how the system works or what is required to work it. Yet there is also resignation to it, or to the drugs or alcohol or gangs or whatever it is that keeps these young men in that system.

It’s beneath some of these more critically aware poems that the raw emotion these men carry can be found. There’s regret, anger, longing, despair, hope. Some gave me a good chuckle; others took my breath away. A few are unsettling, or difficult to make sense of – a couple are reproduced exactly as the writer wrote them, in their own handwriting, which were stark reminders that even the capability to write at all is a privilege some of these men have never had.

I was asked to give particular thought to this book’s suitability for adolescents. There was one poem that referenced being born and raised in Ōtaki, where I grew up myself. I was struck by the sense that I shared something with this writer, our tūrangawaewae, and yet the trajectories of our lives could not be more different. I would recommend any teenager – especially young men – find something that they recognise in these pages and question, like I did, why they aren’t in the writers’ shoes. There is strong and offensive language throughout, but as the collection’s title says: these poems are soliloquies of youth. This is the language of our rangatahi. As attributed to ‘Andre’ in the beginning of this book: ‘If nobody listens then no one will know.’ .

How Did I Get Here? Soliloquies of Youth

by the YPs of Te Puna Wai o Tūhinapō Youth Justice ResidenceEdited by Ben Brown

Published by The Cuba Press

RRP $25.00

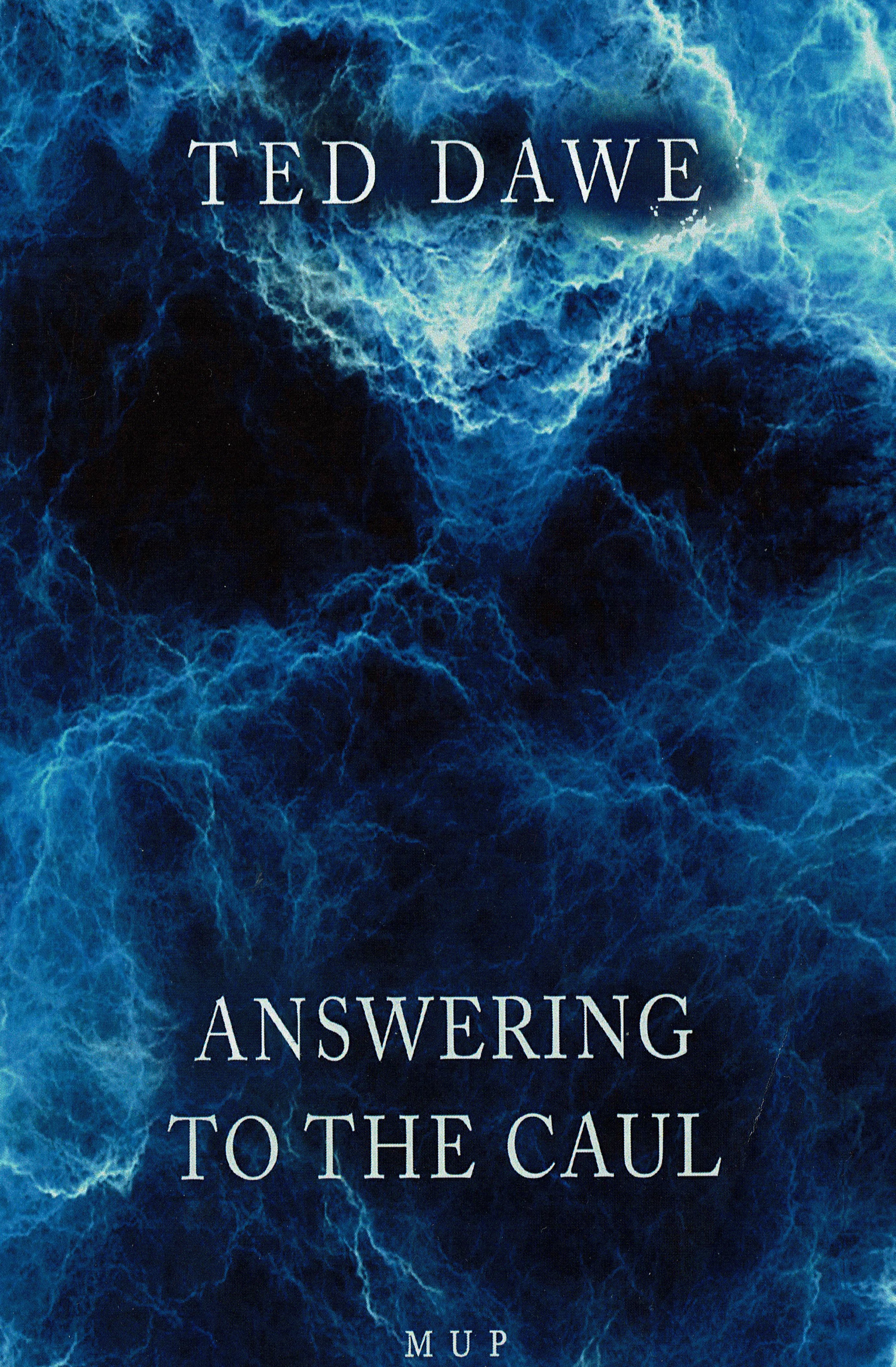

Answering to the Caul by Ted Dawe (Mangakino University Press)

The first thing that someone about to read this book should know is this: it is not, as the title, cover, and blurb suggests, a book with strong supernatural elements. Does that mean it shouldn’t be read? Not at all. But it does mean the book wasn’t quite what I thought it was going to be, for better or worse.

Answering to the Caul is the next novel by Ted Dawe, author of Into the River, which won the inaugural NZ Post Margaret Mahy Book of the Year award in the 2013 New Zealand Post Children’s Book Awards. Dawe’s literary prowess is therefore obvious and very much present in Answering to the Caul – a story about the tragic life of Andrei Reti, who was born in a caul. A caul, as Andrei explains at the beginning of the novel, is the membrane enclosing a foetus before birth, sometimes enveloping the head when a baby is born. This occurrence is said to grant those born in a caul with immunity to drowning. Andrei is one such ‘caul-bearer’, and, as the story of his life from childhood to adulthood proves, his caul exacts a price for its protection.

For most of the book, Answering to the Caul reads a bit like an autobiography, with no real plot. Andrei is a David Copperfield-esque narrator, simply recounting one life event to the next. It speaks to the quality of the narration, which I found brilliantly clever, witty, and engaging, that I was more than happy to just go along for the ride and see whatever situation Andrei blundered into next. As a narrator, Andrei is a bit of an oddball and a cynic, but it’s his detached, meandering narration that endears him to the reader – and results in the most brutal of gut punches when he does abruptly rip the carpet out from underneath you.

As a narrator, Andrei is a bit of an oddball and a cynic, but it’s his detached, meandering narration that endears him to the reader

These moments of tragedy, which serve as catalysts for the regular change in Andrei’s life, bring me to the major issue I have with the novel, which relates back to my opening point regarding the lack of supernatural elements. This, in itself, is not a flaw – I’m not exclusively a reader of speculative fiction – but I did find it an issue when the book seems to think the caul has a much greater role in the story than it actually does. It’s implied that the caul is the source of all the tragedy that befalls Andrei, but the reality is that the caul doesn’t actually feature very much, and I felt the few references Andrei makes to it could actually be removed with no real impact on the novel as a whole. The caul’s significance is made much clearer by the end of the novel, but this climax is brief and undersold; it also mostly happens off the page. Andrei refers to it as his ‘mythic battle’ with the caul, a description that feels undeserved given both its brevity and the very mundane realism of the rest of the text.

I got the impression that this is a novel trying to be two different things: on the one hand a speculative novel, on the other a biographical fiction. The acknowledgements at the end actually suggest this was the case, with two quite separate ideas coming together over time. Unfortunately, I just wasn’t convinced of the caul’s place in this story.

I got the impression that this is a novel trying to be two different things: on the one hand a speculative novel, on the other a biographical fiction.

With all that said, Answering to the Caul still works as a realist novel about growth, loss, guilt, and whānau. One thing that I adored about it was its representation of real-life Aotearoa; not only of the familiar speech and landmarks but also a careful but seamless presence of Māori that I found incredibly refreshing. In particular, for me, seeing my small hometown of Ōtaki replicated in the pages of a novel (right down to a shop that existed in my childhood called Edhouse’s!) was an unexpected delight.

Don’t let the speculative façade put you off: Answering to the Caul is a funny, tragic, fundamentally Aotearoa novel well worth a read.

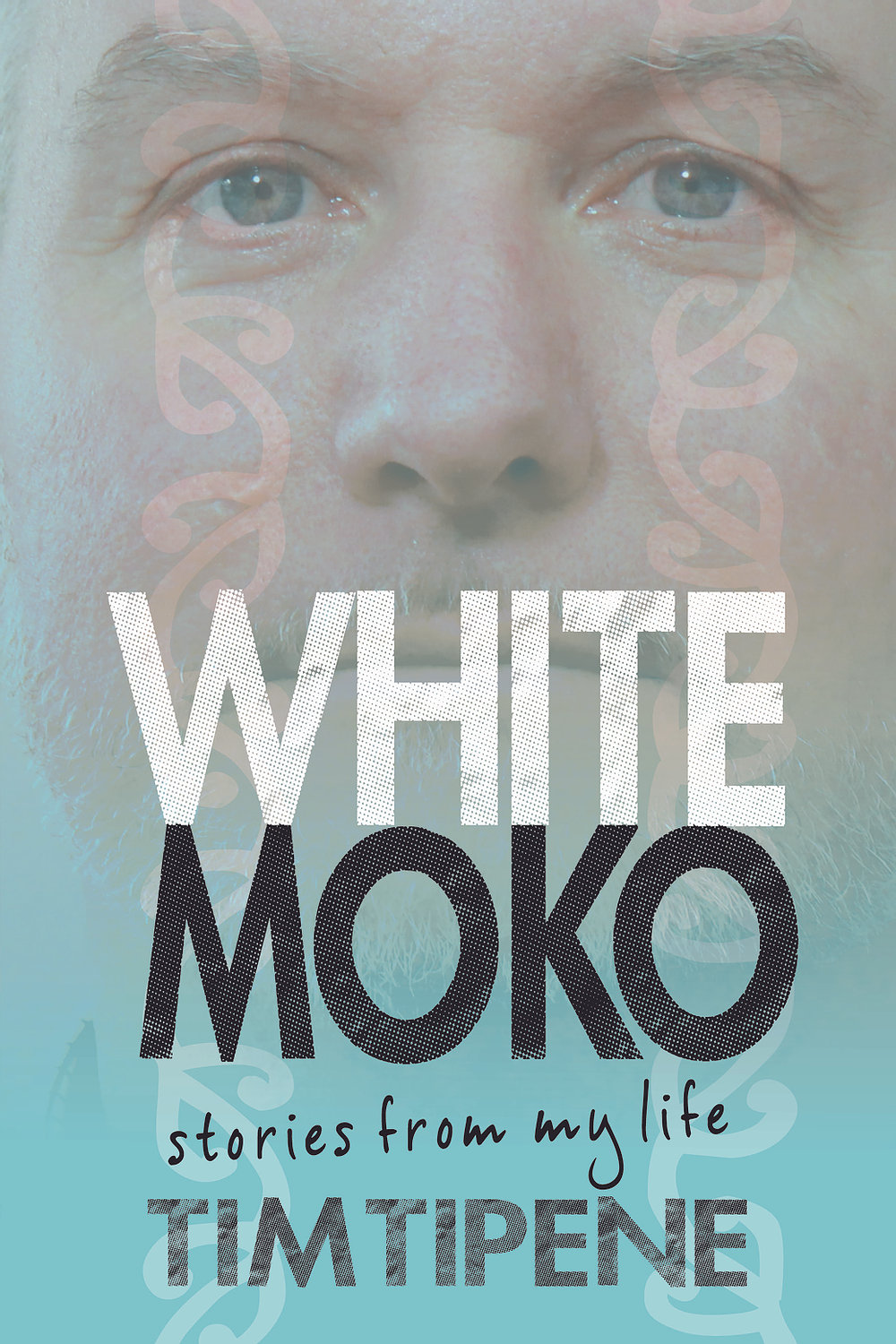

White Moko: Stories From my Life by Tim Tipene (OneTree House)

Content warning: references to child abuse and sexual assault

In recent years, the shocking extent of child abuse in Aotearoa has begun to receive public attention. Much of the reporting and narratives feature Māori as both the victims and perpetrators. White Moko is something of an anomaly within this context; it’s a memoir by a Pākehā man, recounting the traumatic abuse he suffered as a boy and young man, in which the aroha of an adoptive whānau helps save him. This is not to say that White Moko is refreshing in any way – abuse is abuse – but in a media and literature market flooded with abusive representations of Māori, it provides a stark point of difference.

This point of difference is established immediately; Tipene was born to Pākehā parents as the product of rape, but adopted by the whānau of his Māori stepfather at the age of two. Despite the love and care with which this whānau treat Tipene, he still struggles to connect with people and place. As a white-presenting Māori man, I related strongly to Tipene’s experiences as a blond-haired, blue-eyed boy carrying a Māori name, and the interrogation of identity that results from it. For Tipene, however, who eventually moves back into the custody of his Pākehā family, this is only the tip of the iceberg.

As a white-presenting Māori man, I related strongly to Tipene’s experiences as a blond-haired, blue-eyed boy carrying a Māori name, and the interrogation of identity that results from it.

Tipene’s accounts of his traumatic upbringing are harrowing to say the least. The writing is honest and frank, yet surprisingly restrained. This restraint is welcome, given that the trauma he describes is often unrelenting. There is a real sense of mounting hopelessness in the myriad ways that people and systems fail Tipene, and I often found myself – like Tipene, I imagine – feeling a wave of affection for the very few people who show him even the most basic of kindnesses.

Tipene’s writing also shows remarkable empathy, particularly for his parents who were mostly responsible for the abuse he suffered. There is deep understanding of the conditions that shaped his parents and influenced their horrific treatment of him, an understanding that may not be deserved but demonstrates the extent to which Tipene has overcome his trauma.

I have some questions about Tipene’s presentation of himself as a Māori author. While Tipene shows incredible empathy for his abusive parents, there is an absence of similar understanding as to why some Māori may have reacted harshly to his claiming to be Māori, or of becoming the Chair of a whānau committee. Tipene tends to brush these experiences off in an assertion of perceived whakapapa Māori rather than reflect on them in the same way he does elsewhere. A deeper analysis of what it means to be Pākehā, raised and loved and educated in te ao Māori, would have been a really interesting addition to these accounts.

A deeper analysis of what it means to be Pākehā, raised and loved and educated in te ao Māori, would have been a really interesting addition to these accounts.

I do also feel the need to comment on the production quality of the book. There were many errors throughout, both typographical and grammatical, which suggest the need for a solid edit and proofread that should have happened before publication.

These factors do not, however, take away from the impact of reading Tipene’s accounts, or his achievements in overcoming them. As a reader who has had the immense privilege of not experiencing the things Tipene has, I was often moved and disgusted by what I read. Tipene has lived through things that no child should, but, as the statistics show, many in Aotearoa have. It is likely for those people, who have been victims of similar abuse, that this book was written. Tipene himself states that he wants his accounts to connect with, and give hope to, people who have experienced such abuse. I suspect, from the honest but careful way in which Tipene has written, that they will.

White Moko would be appropriate for mature teenagers and select chapters may also be suitable for use in teaching younger readers.

Tihema Baker

Tihema Baker is a Māori writer of Te Āti Awa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Raukawa te Au ki te Tonga, and Ngāti Toa Rangatira. He is the author of YA novels Watchedand Exceptional, and has completed a Master of Arts in Creative Writing at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s International Institute of Modern Letters.