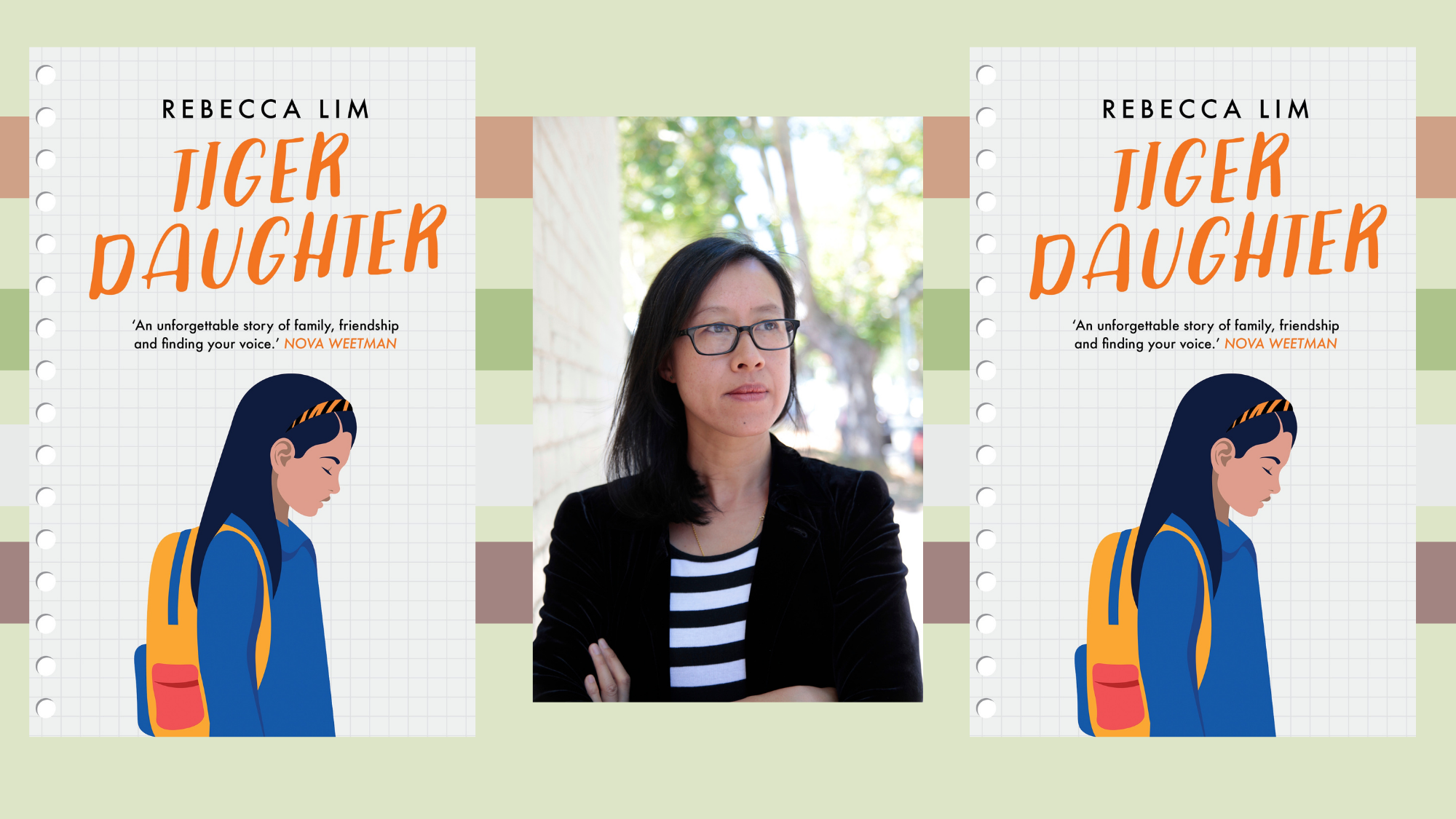

Rebecca Lim is an Australian writer, illustrator and editor and the author of over twenty books, including The Astrologer’s Daughter (A Kirkus Best Book of 2015 and CBCA Notable Book for Older Readers), Afterlight and Wraith. Her work has been shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards and INDIEFAB Book of the Year Awards, shortlisted multiple times for the Aurealis Awards and Davitt Awards, and longlisted for the Gold Inky Award and the David Gemmell Legend Award. Ruth Agnew spoke to her about her latest book, Tiger Daughter. You can read the review here.

Ruth Agnew:

The protagonist in Tiger Daughter, Wen, is the only child of Chinese immigrants who uses what little control she does have in her life to do something incredibly powerful. It’s wonderful to find such an interesting, inspirational female Asian character in a book for young readers, but sadly, all too rare. How do you think we can encourage other writers to create more nuanced portrayals of Asian and other underrepresented ethnicities in youth fiction?

Rebecca Lim:

I think it’s up to gatekeepers and parents to say, every child’s story is important and every child’s story deserves to be published.

I’m not sure if it is this way in New Zealand, but here in Australia there is a default setting where the central character is a white child, usually a boy, because publishers are marketing to the mythical audience and perpetuating the belief that boys won’t read a book with a girl on the cover. We should encourage our kids to read more widely, and to write down their own stories. We need to break that mindset of there’s only one kind of reading audience, which is an educated white straight able-bodied one, because that isn’t true, and every child’s story deserves to be heard. I think we need to say to children, your story is just as important as everyone else’s. Even if it’s not published you need to write into that gap or seek books out that depict a more diverse perspective, because that’s the only way to get those stories heard.

We should encourage our kids to read more widely, and to write down their own stories. We need to break that mindset of there’s only one kind of reading audience, which is an educated white straight able-bodied one, because that isn’t true, and every child’s story deserves to be heard.

You know that quiet kid in the class next to you, maybe he’s got some problem that he is struggling with. He may be antisocial because he’s really terrified; perhaps he comes from a different background, or maybe he has a mentally ill parent. Finding a book with a character that reflects his experience can be really empowering. It’s trying to get that empathy push, through parents, libraries and teachers, to get kids to read more widely.

RA:

Speaking from a personal perspective, as a New Zealander of Chinese descent, it would have meant so much to discover a powerful protagonist like Wen. It is so empowering for young readers to see themselves and their experiences reflected in the books they read, yet it is still so rare to find Asian heroes in children’s stories. When you were a child, which fictional character did you find that reflected your culture and experience?

RL:

Really, there weren’t any positive Asian characters that I found when I was growing up. When I came to Australia in the 1970s, and throughout the 80s too, there were very few faces on television that showed any kind of cultural diversity. If there was a depiction of a Chinese family, they would be shown doing something like stealing and eating the neighbour’s dog, so really reinforcing those racist stereotypes. That’s why we need to let more voices in. Everywhere around the world we need to reassess who has the power and who is setting the agendas, not only with fictional characters, but we have to look at who is behind things like memes, video games, politics, sport, and get that power shifted so that we can all see ourselves reflected.

RA:

You’ve said that you write “to give your children a face in society”. How do you feel about some of the problematic depictions of Asian characters in children’s fiction written from a Eurocentric perspective, that perpetuate racist stereotypes? Examples that come to mind are Cho Chang in J K Rowlings’ Harry Potter series, Ook and Gluk in Dav Pilkey’s Captain Underpants: Kung-Fu Cavemen From the Future.

RL:

When you’ve got people from outside a culture writing the culture, you end up with these characters who are in name and face Asian, but everything they do and everything they say could just be a white person; there’s no cultural accuracy or acknowledgement of different experiences within a cultural group. So we need to let more voices in; we need to hear from Asian writers or disabled writers, queer writers, people who inhabit intersections. It’s about a power shift; we are seeing it with Black Lives Matter, and everywhere around the world we need to reassess who’s got the power, who is setting the agenda, and that power so that we can all see a reflection of ourselves.

We need to let more voices in; we need to hear from Asian writers or disabled writers, queer writers, people who inhabit intersections. It’s about a power shift; we are seeing it with Black Lives Matter, and everywhere around the world we need to reassess who’s got the power, who is setting the agenda, and that power so that we can all see a reflection of ourselves.

RA:

Where did you get inspiration for the character of Wen? Is she based on a particular person? Are there aspects of yourself in her?

RL:

I think Wen is who I wanted to be when I was growing up; she’s more vocal and outspoken than I was at that age; she’s a forthright, ballsy Chinese girl, she’s strong, and stands up for herself and challenges her parental restrictions. I’ve written a character with absolutely zero agency, but even in that tiny limited space she has she is actually trying to carve out her own agency and to change the lives of other people.

I think our next generation has got that fire in them, and they are prepared to find that power within themselves. I look at my daughters, who are very confident young women, and Wen is like a stepping stone between me and them. Each of my daughters illustrated the pictures drawn by the characters of Henry and Wen, and it was lovely to have them involved.

I think our next generation has got that fire in them, and they are prepared to find that power within themselves. I look at my daughters, who are very confident young women, and Wen is like a stepping stone between me and them.

RA:

You don’t shy away from tackling challenging issues in your books for young readers; Tiger Daughter, includes parental suicide, domestic violence and anti-Asian racism, all seen through the eyes of thirteen-year-old Wen. Why did you choose to integrate such challenging themes? What would you say to someone who believes subjects like a child’s mother taking her own life are not appropriate for a children’s book?

RL:

To me, opening up the conversation about tough topics is vital. I know my own children really appreciate when I have mature discussions with them, and I thought, if my kids can process ideas about these big issues, things like Black Lives Matter and domestic violence, kids generally can cope too. It is even more important for children trapped in an unhealthy or unsafe situation.

I think we have a tendency to sugarcoat things for children, and think that they can’t handle this stuff, but the reality is that children are grappling with these really big issues already. If we don’t address these tough issues in children’s fiction, if we pretend they don’t exist, we send the message to children that what they are experiencing isn’t important, or that they’re alone. If a child is, for example, experiencing grief, or in a violent home, reading about a child in similar or relatable circumstances can help them make sense of what they are going through and legitimise their experience.

I think we have a tendency to sugarcoat things for children, and think that they can’t handle this stuff, but the reality is that children are grappling with these really big issues already. If we don’t address these tough issues in children’s fiction, if we pretend they don’t exist, we send the message to children that what they are experiencing isn’t important, or that they’re alone.

Teachers and parents need to realise children don’t need to be wrapped up in cotton wool, and that they will have a lot of burning questions for adults in their lives. I think a better sort of school experience for a lot of kids would be if they knew that the adults around them were open to speaking about really complex difficult issues.

RA:

Tiger Daughter depicts the struggles of a migrant family in crisis; Wen’s father has repeatedly failed the specialist medical exam necessary to work as a surgeon in Australia, so instead works as “the angriest, most ruthless floor manager in the history of the Hai Tong Tai seafood restaurant”. He takes his frustrations out on his wife and daughter, expecting them to adhere to his strict rules, and frequently flying into violent rages. Wen’s mother gradually starts to push back against his controlling behaviour, but does not leave the marriage. Why did you choose to have Wen’s mother remain in a relationship marred by domestic violence? Did you consider a different outcome, where she and Wen leave?

RL:

What I wanted to show was a ‘warts and all’ depiction of this family, and there are a lot of complex issues I wanted to cover. Many migrant women in situations like Wen’s mother feel trapped because they don’t have language or they don’t necessarily have the financial means to escape. So I had her saying this is the choice I made, and we just have to make the most of it, whereas it would have been quite a different story if I had her pack her bags and leave. It would have changed Henry’s story; he would have just sunk without Wen, and they wouldn’t have made it to the exam, so there wouldn’t have been a positive outcome for them. I do think the more realistic story is that she flees with her wife and daughter, and then it becomes a story of survival. That may be another story to write, but with Tiger Daughter I just wanted there to be a positive outcome, and to show how with the support of your community you actually work through these problems.

I also wanted to open up the question of what you can do when your home life is unsafe, and help kids think about how they can seek help.

RA:

Wen and her mother prepare meals and leave them at Henry’s door to support him and his father following the suicide of Henry’s mother. The preparation, presentation and means of delivery are so carefully considered, and it becomes very clear that food is a love language between these families. What did you want readers to understand from these food rituals?

RL:

Sometimes the only way you can help your fellow person is to give them food. I wanted to show the kind of situation where you really want to show you care, there are ways to show that.

The instinct we might have with Henry is to drag him out of his house and wrap him in a big hug, but that wouldn’t be the right response for him. So we can take that message and show our children the safety to feel their emotions and how they manifest them is ok, and they are supported.

RA:

There is a perception, from a Eurocentric view, that the Tiger Parent trope in Asian families is uncaring and cruel. My perspective from being raised with a Chinese mother’s high expectations is that it is another kind of love language; her disappointment with unsatisfactory results was because she wanted us to have the best possible future, and she believed we were capable of achieving that. How do you think we should reframe negative Asian stereotypes like that?

RL:

Yes, that drive comes from a place of love and believing your children are strong enough to do it, which can be empowering. I guess the Asian way of raising children is quite different from the Western environment we’ve been brought up in, so there is that clash of ideals there. That’s why I wanted to show Wen finding her way of being in both worlds without it being a constant conflict.

I also wanted to challenge the idea that Asian women are submissive and don’t have a voice, because we see that even in the limited space that Wen’s mother has, she is actually carving out her own agency and making other people’s lives better.

I also wanted to challenge the idea that Asian women are submissive and don’t have a voice, because we see that even in the limited space that Wen’s mother has, she is actually carving out her own agency and making other people’s lives better.

It is up to all of us from non-European backgrounds to show our culture authentically, with the good and bad parts, but also show that the negative stereotypes people have about us can be flipped to show strength, endurance, compassion and empathy.

When awful things happen, like people getting attacked in the street for the way they look, we have to keep rising up and saying this is not good enough, it is not human to do that. We have to push aside the fear and the anger and the sorrow and just keep getting the positive stories out there.

Ruth Oy Har Agnew

Ruth is a writer and teacher of Chinese and Pākehā descent from Ōtautahi Christchurch. She has written for Theatreview, The Press, Stuff, Flat Takahe, What’s Up Christchurch, and the Playmarket Annual. She is an experienced actor, and currently works supporting young performers as a speech and drama teacher.