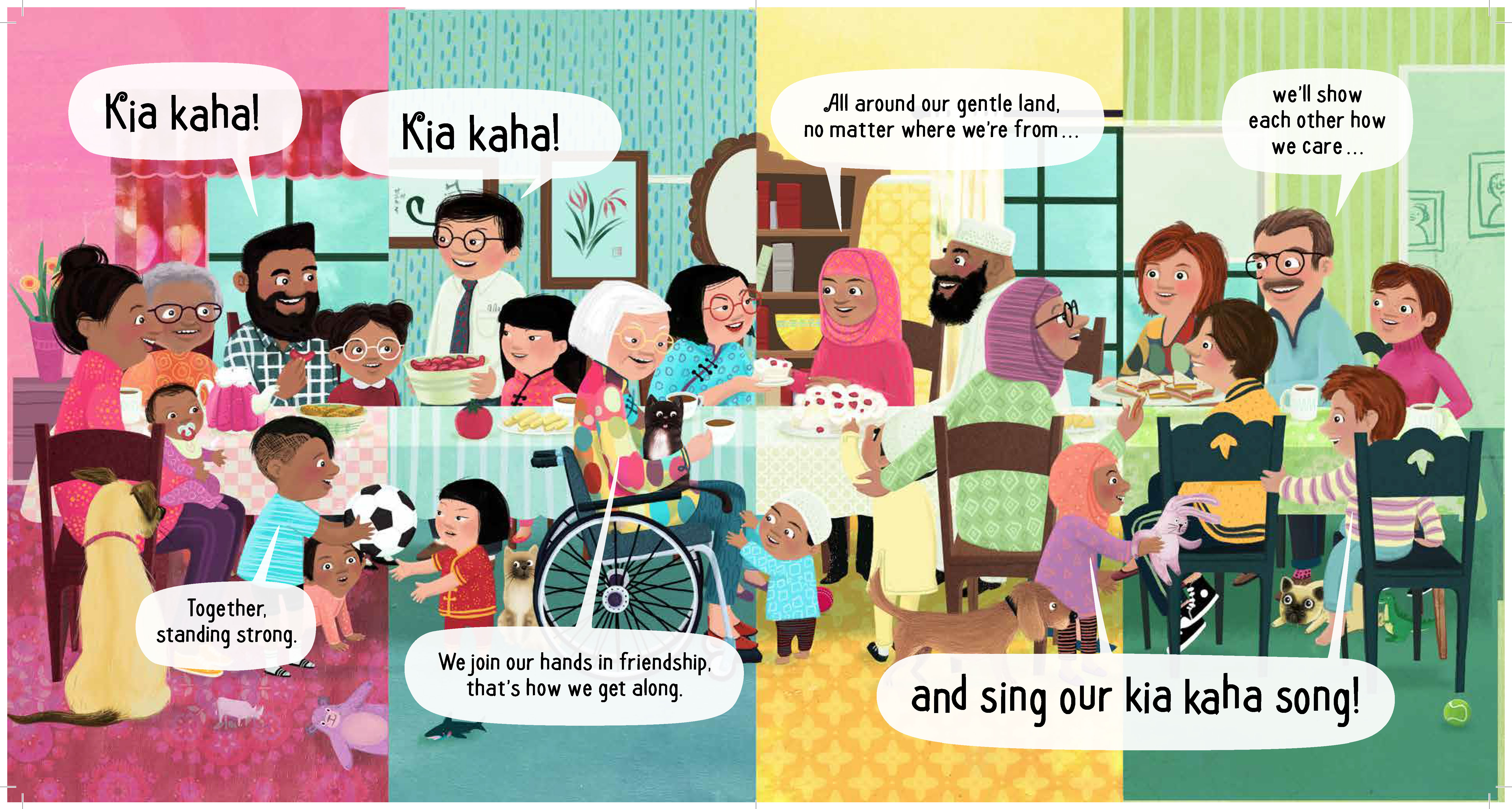

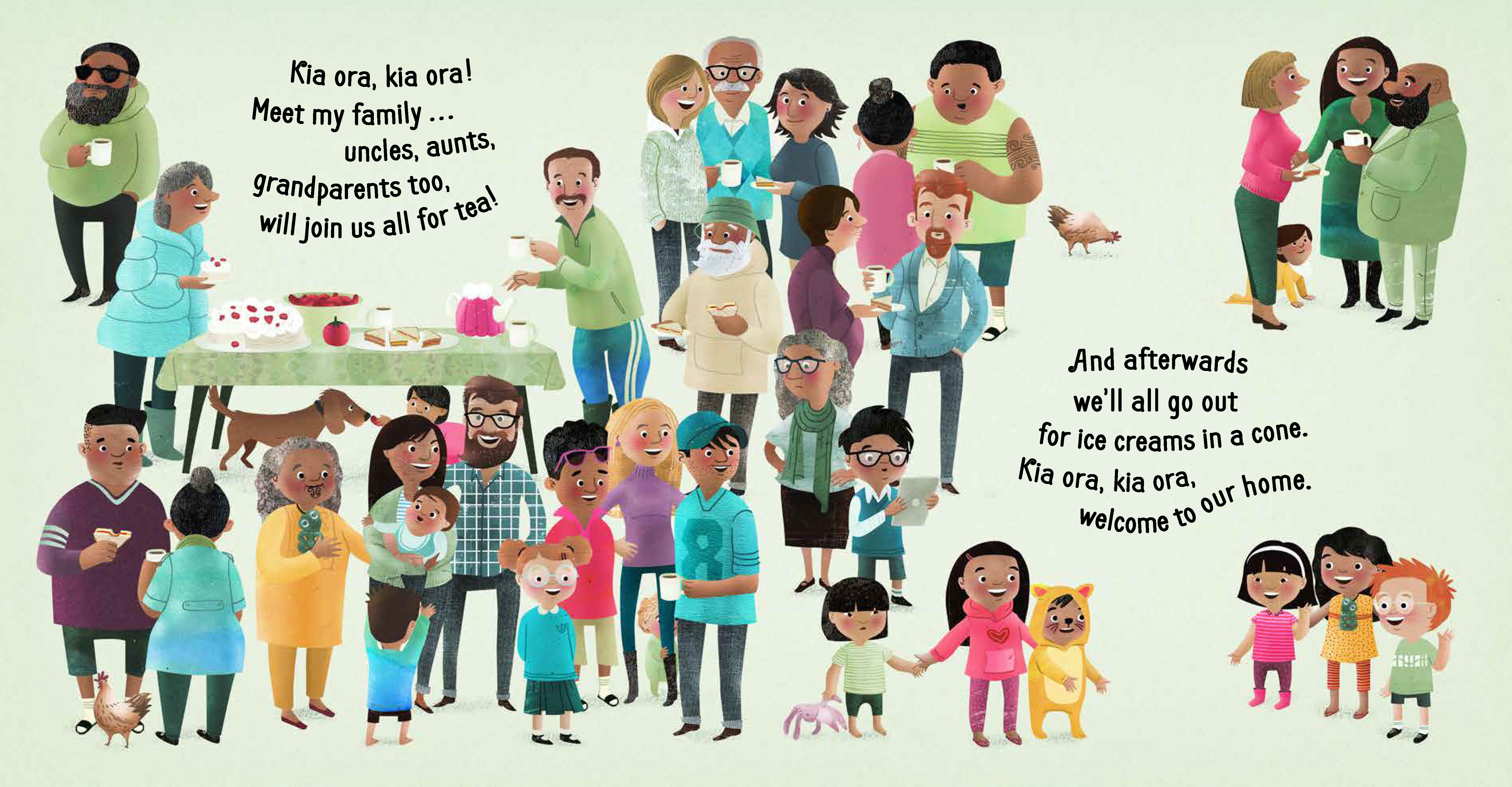

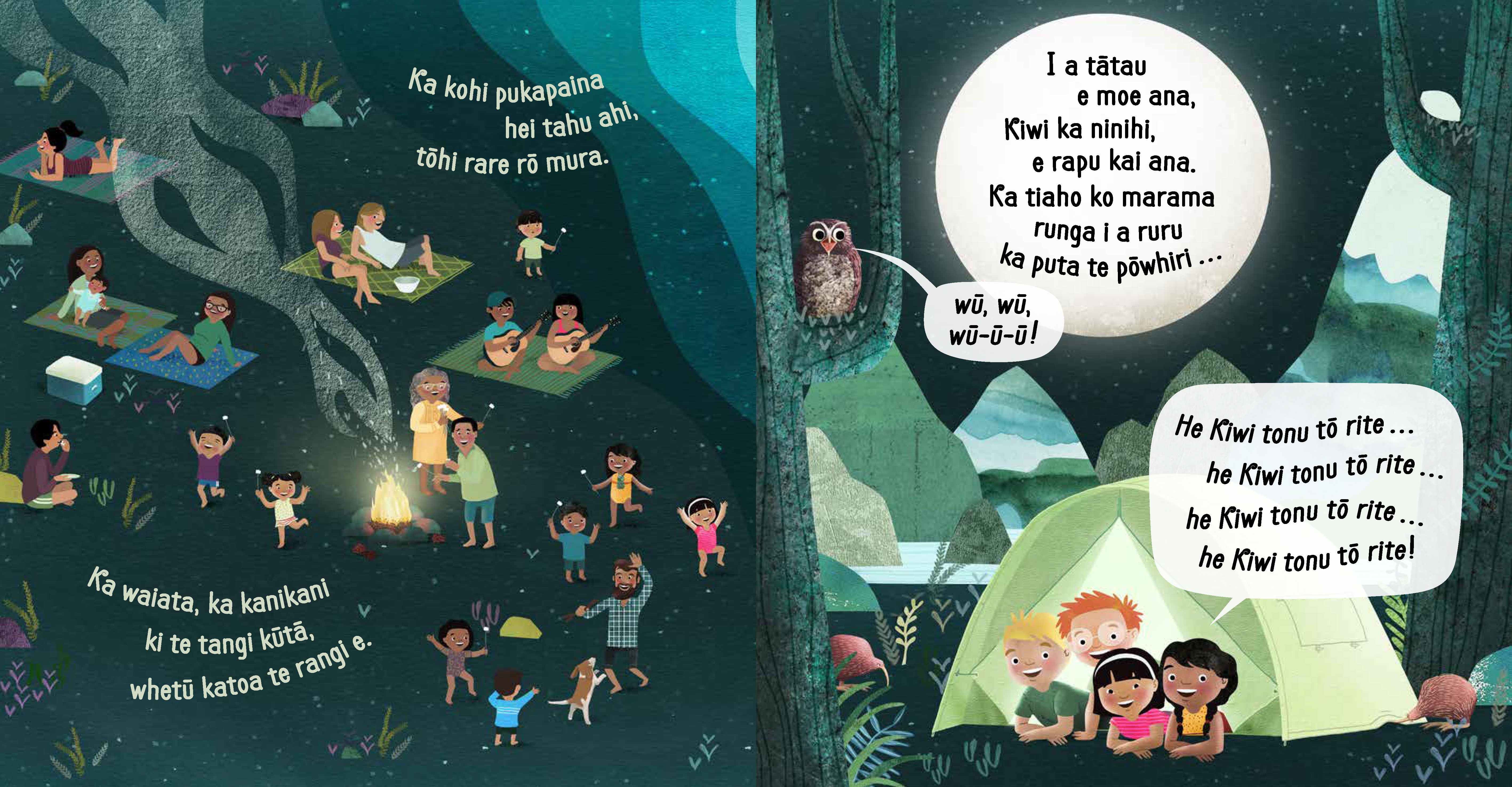

Many of our wonderful picture book writers are both musicians and writers. Diana Neild, writer of Daddy Monster A-B-C and the Piggity-Wiggity series (if you don’t know these, look them up!) and June Pitman-Hayes, writer of Kia ora! You can be a Kiwi too, and Kia Kaha! Together, standing strong are two such writer/musicians. They have a chat about their inspirations and their publications.

June: What inspired you to write for children?

Diana: I saw that a few pop stars and royals were publishing children’s books that were pretty awful and thought I could do better!

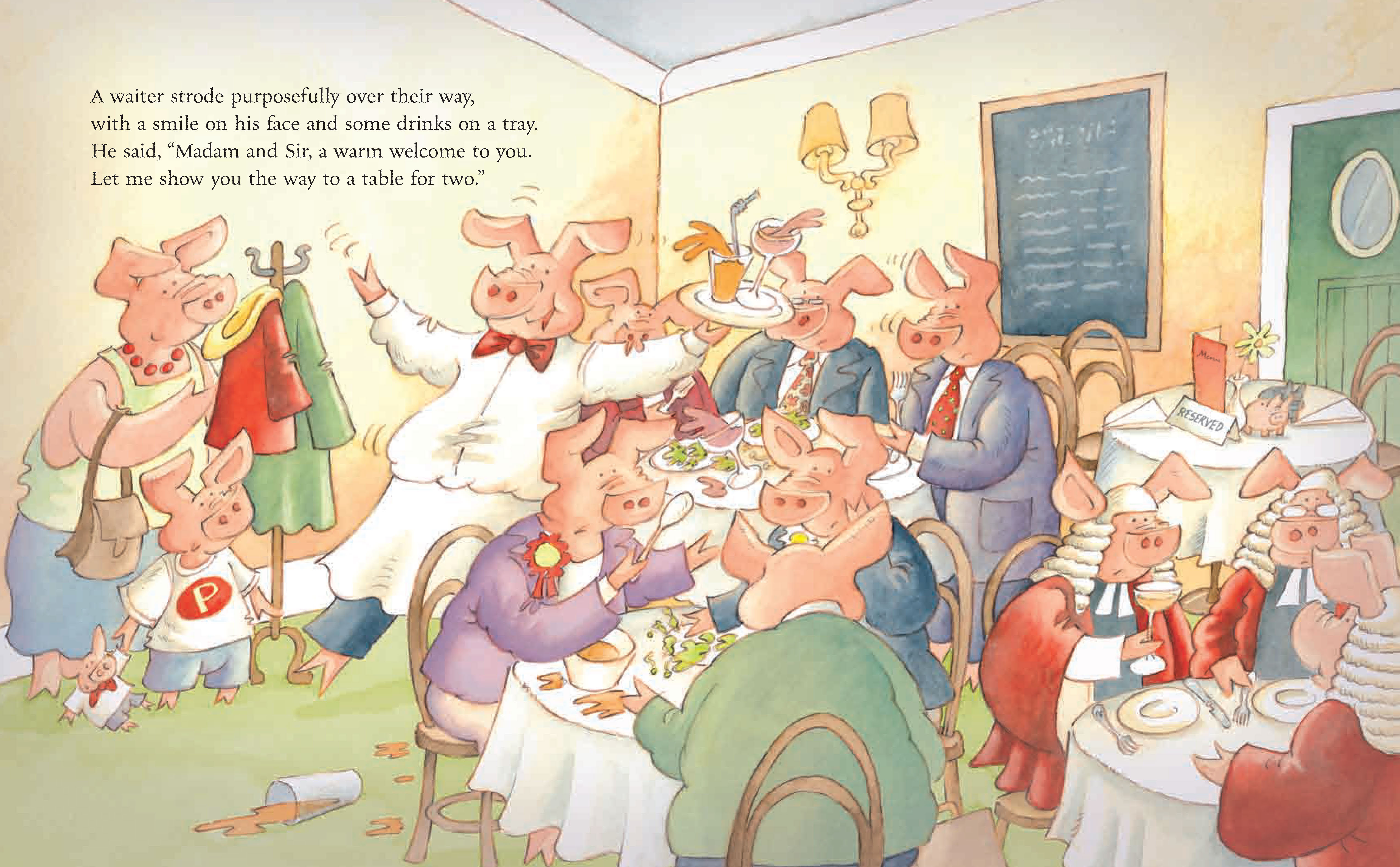

My main motive for the content was to give dads a fair go. There were so many children’s books around with a dad in them that did dumb things and generally made to look stupid. I wanted to make a story where the dad was a hero for his kids, so in most of the Piggity stories the dad solves the problem.

J: Yes, I think hero dads in stories are a great idea. Affirming for them too, that they are important in their children’s lives, caring, teaching them to read, having adventures, nurturing, etc.

D: Do you sit down to consciously write, or do you do other things and let the words swim round in your head and catch the ones you want?

I do it that way when I’m writing rhyme, but now I’m writing books for 8-12 year-olds I have to sit at the computer. Annoyingly, I can’t have the radio on, because even though I’m not rhyming, the words have to have the right rhythm, and sometimes Mozart and Miles Davis won’t play in time to my words. Most inconsiderate.

… the words have to have the right rhythm, and sometimes Mozart and Miles Davis won’t play in time to my words. Most inconsiderate.

J: I find it difficult to sit down and consciously write. I’m used to making up stories, and my children always preferred to listen to the stories I made up. Often ideas come to me when I’m in the middle of something, so I find pen and paper and scribble those ideas down. I work well when I’m pushing a deadline and describe myself as a ‘crammer’.

My next book was a strange creative experience. I was working to a brief, but it just wouldn’t happen. I almost gave up, but decided to give it one more go and write from the heart. Boom – the new book idea flowed. Because I’m writing music and words together, I can’t have the distraction of music playing.

I liked the fact that you didn’t use baby language in Piggity Wiggity, and I was totally drawn into the ’30’s construction’ theme. I was feeling for children with long names, how excruciating it would be for them when the time came to learn how to write their names! I’m glad I was the recipient of the traditional first, middle, surname scenario, although I’d have preferred to have been called Jenny. My friend Jenny’s mother always sent her to school with oranges whose skins peeled off in the easiest and most perfect spiral way. Ah yes, cool things happened if your name was Jenny, I thought.

My friend Jenny’s mother always sent her to school with oranges whose skins peeled off in the easiest and most perfect spiral way. Ah yes, cool things happened if your name was Jenny, I thought.

D: June is a great name—so many things rhyme with it. That diva June is coming soon, she’ll start to croon at twelve past noon – I hope she’ll sing that song “Blue Moon”, it’s always been my favourite tune. Rhymes about Jenny? There aren’t any!

J: What are the sparks of your next book?

D: Sparks are cheap—it’s putting them into practise that’s the trick. Firstly, I build my characters, and then I form the story from their personalities, interests and abilities. I’m writing three books for 7-12 year-olds at present—I thought if I wrote a whole heap of different stuff then someone in some distant future era might possibly want to publish one of them.

I note that you find writing to be therapy.

Do you handwrite or type? If I handwrite it seems more part of what I’m feeling, and I can screw it up or burn it straight away—much more satisfying than deleting.

J: I tend to move between hand-writing and typing depending on the mood I’m in, and where I am. Screwing up or burning writing is a powerful, cathartic way to expel creative energy. Note to self—create a fire pit.

Screwing up or burning writing is a powerful, cathartic way to expel creative energy. Note to self—create a fire pit.

D: You are a wonderful singer. I always think it’s unfair that some people are born with a voice to sing, while us others have to spend years learning instruments to sound half-way decent. Not that I don’t think you would have put lots of work in too, I’m just hugely jealous of singers. Especially jazz singers.

J: I envy people who are able to play an instrument and read music! When I write music for my children’s books, I play my ukulele by ear and haven’t advanced much past the four basic chords my mother taught me when I was three. When I compose music for adults, I record what is coming through me into my mobile phone, and then work alongside my producer who patiently extracts what I’m feeling musically, and then together we build the instrumentation. It’s a weird process, but it seems to work well.

D: I wish my mother had taught me ukulele chords when I was three. I spent an entire summer once learning two chords on the guitar and there’s still a half-second gap between them.

You and I both grew up in rural coastal New Zealand, speared flounder, had grandparents with flame trees, and thought that every other child grew up that way. We also put great value on Redband gumboots. My Redbands are my pride and joy, and I was horrified to see that one of them has a hole in them. I’ll buy more, but what to do with the old ones? I can’t just biff them, they’ve been my friends—seen me through hours of digging, dump trips and several sneaky trips through the house. And if only one has a hole, what do I say to the other? “Sorry—you’re no use without a partner!”

My Redbands are my pride and joy, and I was horrified to see that one of them has a hole in them. I’ll buy more, but what to do with the old ones?

J: I love spearing flounder to this day, although they are harder to find along Terenga Paraoa these days.

I remember getting my first pair of Redbands when I went farming. I was a bit skinnier then, so there was a gap between the top of my gumboots and my legs; enough for cow poo to slide into (we milked cows in a herringbone shed and I somehow managed to get covered from head to foot in their manure!). I did eventually grow into them, outwards not upwards.

On flame trees, I’ve just returned to the land where I was born, and they’re still here reaching their prickly branches out over what was once my grandparents’ water well. I love their flowers, but they do smother the native bush. My sister and I used to love playing roly-poly down the kikuyu bank beneath their dappled shade during summer.

D: My sister and I made gardens in the bush behind our house. I had a seedling from my grandfather’s flame tree and I willed that thing to grow, but it did not. I was heartbroken but it sounds like I saved myself some scratches.

Tell me more about your childhood. I remember how my mother would give me and my little brother (aged five and ten) some sausages, bread, and a box of matches, and off we’d go for the whole day, making a fire on some spot on the farm and cooking our lunch.

I remember how my mother would give me and my little brother (aged five and ten) some sausages, bread, and a box of matches, and off we’d go for the whole day, making a fire on some spot on the farm and cooking our lunch.

J: We lived off the land mostly, and of course kaimoana was a staple diet for us. Nana would send my sister and I off with a kete to the creek to gather watercress, with strict instructions to dig for lady pipi (the long, slender shellfish) on the way. ‘Make sure you rinse them out well’, she’d yell as we disappeared down the track to the beach. She was an incredible woman, and incredibly old when I was born. She was also illiterate, so the ability for my sister and I to read was her ‘window’ to the outside world.

She spoke fluent Te Reo Māori but we weren’t encouraged to—we’d get ahead in the world if we ‘became Pākehā’ in some ways.

D: Do you think that listening to two languages made you more aware of the musical sound of words, and had an influence on your music and writing?

J: Yes, absolutely. Māori language softens everything by taking away the sharp edges, especially when used in song; the ‘wh’s’ and ‘ng’s’. Recently I released an extended play album entitled Whenua, Aroha, Mārama. One of the songs on this album entitled ‘I Wanna Call You Up’ is a good example of this ‘softening’.

D: Tell me more about your grandmother. Mine lived on the farm with us until I was about seven. She was rather strict and made us walk to the bathroom with our hands held above our heads so we wouldn’t dirty anything. She wore awesome clothes and had been a ballet dancer.

She was rather strict and made us walk to the bathroom with our hands held above our heads so we wouldn’t dirty anything.

J: My nana was also strict, but there was a deep kindness and calm about her. One of my special memories of her was warming up oranges in the coal range, and making buttered Arrowroot biscuit ‘sandwiches’ for our afternoon tea. In summer we’d eat them out on the lawn above the herb garden, and in winter we’d huddle in front of the coal range.

What is a special memory for you of your grandmother?

D: I remember her encouraging me with my music, even when I sounded terrible. She was a painter as well as a dancer, sewed and played the piano. Having brought up a family in the depression she was creative and resourceful. I’d be practising something in the spare room at her place and if I stopped for even half a minute she’d call down the hall “Keep going!” We learned respect from her in a big way—I never ever heard her say anything bad about anyone.

What was your school like when you were young?

J: I went to Onerahi School. I remember the day my mother took me to get enrolled. We were in the playground and I got stuck on the metal slide. I was absolutely petrified and the slide was roasting hot! Some children came along and helped me down. I didn’t go on that slide for a long, long time after that. I did draw on that memory when writing Kia Kaha though.

D: One of my strongest memories of school was when I was five. Not knowing what to do with the horrible school cocoa, I poured it into a boy’s gumboot at lunchtime when no one was looking, then stood round with everyone saying “ooooh yuck!” when he put his boots on at 3pm. Poor thing didn’t even know what the stuff was—just that it was brown and liquid.

J: We used to get milk in glass bottles to drink every morning and sometimes it used to sit in the sun for a bit too long. One of the boys, John Love, used to make milkshakes out of his, using ground up chalk dust—revolting!

Diana Neild

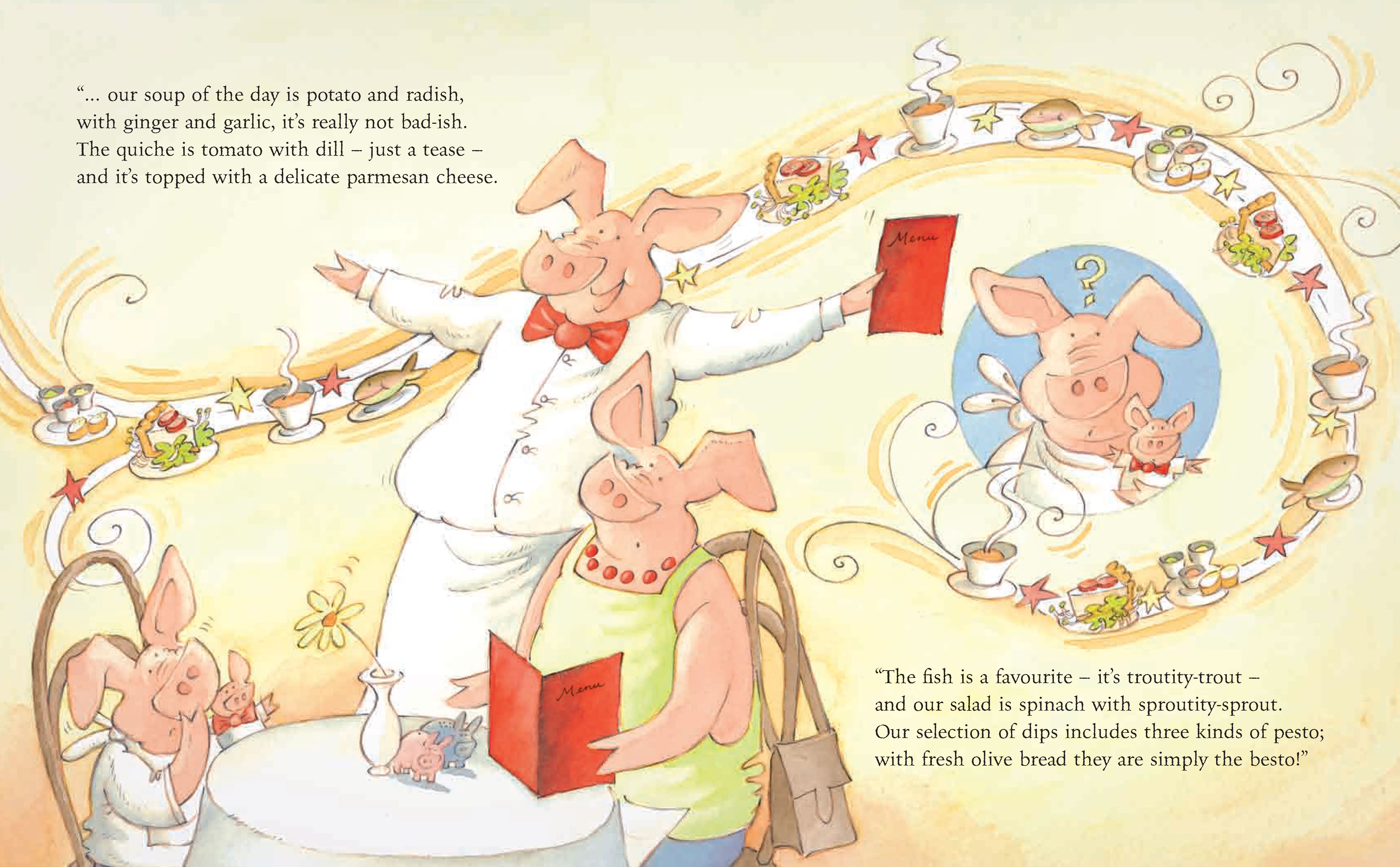

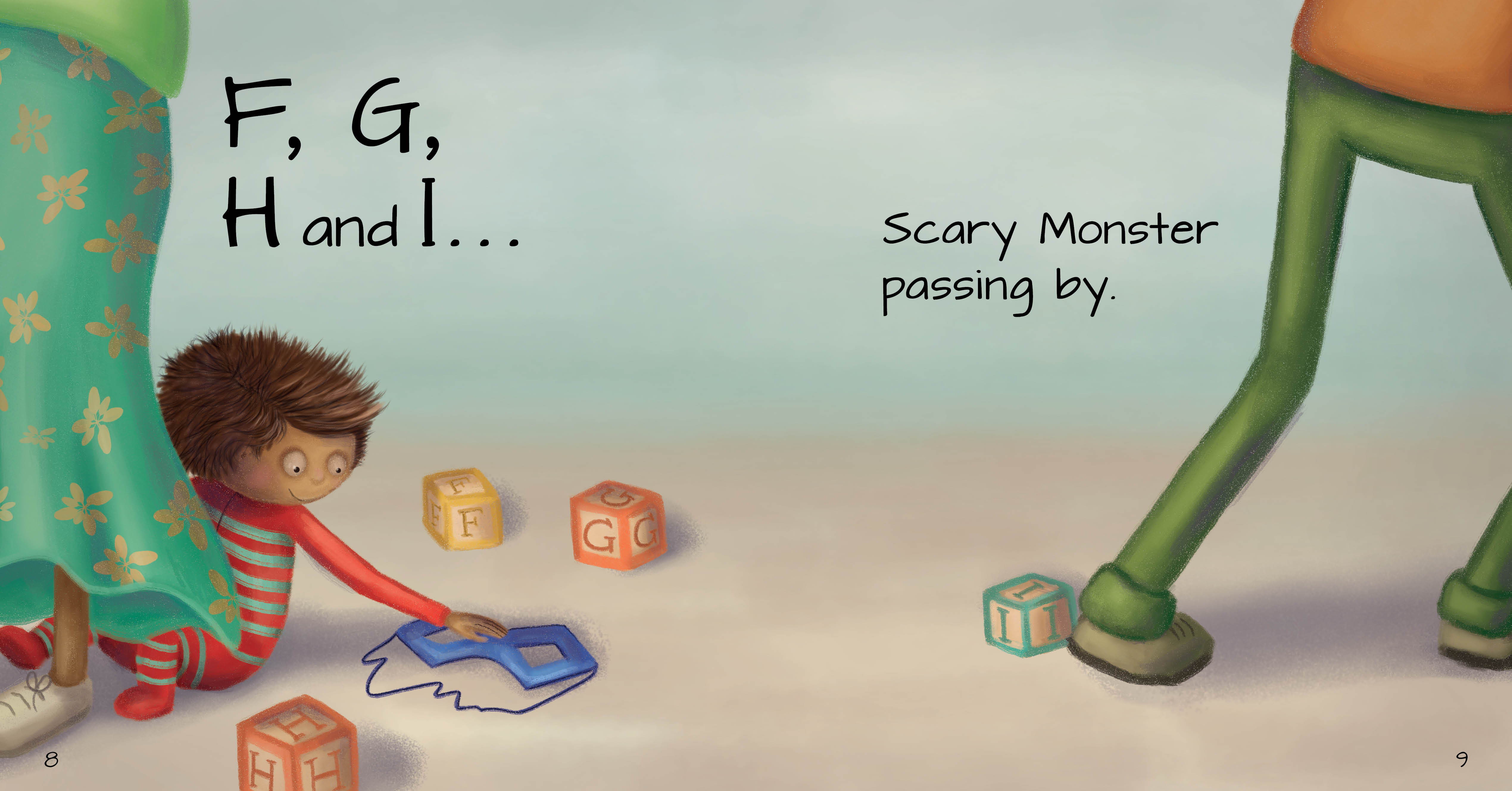

Diana Neild is the creator of an ongoing number of dresses, knitted garments, letters to friends, the Piggity-Wiggity series, Daddy Monster ABC, and a truckload of unpublished rhyme. She plays at concerts and functions in a covers band, an all-female sax quartet, a classical quartet, and teaches flute and piano.