While publishers were paused, we asked one of our favourite kiwi authors to kick off a new series for us. Barbara Else tells us about her New Zealand book memories, and why she isn’t so sure that The Cradle Ship and Our Street should be reissued for today’s market.

When I was learning to read there were hardly any children’s books by New Zealanders. There were even fewer from local publishers. Thank goodness there was the New Zealand School Journal for when you were older. But at first anything that came under my bookworm-nose was from Britain or the USA. I assumed that apart from Māori legends stories simply were always set overseas, in other lands.

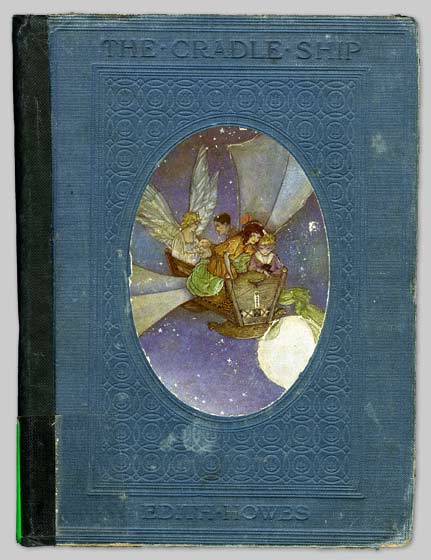

Yet here was a book by a New Zealander on the shelves of our own home. By age six I’d read it several times. It was The Cradle Ship, by Edith Howes published in 1916 by Cassell and Company, Ltd, London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne.

Yet here was a book by a New Zealander on the shelves of our own home.

Howes, a teacher, published several books. Our copy of The Cradle Ship had my mother’s name inked on the flyleaf. I suppose she may have used it in her own primary teaching career during the Depression and World War 2. I still have it because Howes was one of NZ’s first children’s authors. It’s falling to pieces.

Howes’s specialty was teaching simple scientific facts in scenarios that young children would find easy to understand, by using fairies and talking plants and animals.

In The Cradle Ship, Win and Twin are surprised that their mother has had a baby. Where do babies come from, they ask Granny? She tells them crossly not to ask questions like that. ‘It’s rude. Run away and don’t be naughty.’

In The Cradle Ship, Win and Twin are surprised that their mother has had a baby. Where do babies come from, they ask Granny?

But Mother, being a Fairy, and Father, being a Poet, are kinder. They leave Granny to mind the house: good. I didn’t like her. And the family rides the Cradle Ship into the starlit night, heading for a biology lesson in Babyland.

Win and Twin learn from drowsy mother Oak how her acorn babies have been made from mother-flowers and father-catkins. They learn about bees, that the drone gives the Queen Bee ‘his little grains’ which join with her little grains to make the eggs. The twins learn about fish babies, and birds and opossums. Finally they meet a human mother who explains that her infant ‘lay and grew in the silken baby-bag beneath my heart.’

These days it sounds sentimental, awful. But in its time the book was innovative. Howes was a revolutionary.

The twins learn about fish babies, and birds and opossums. Finally they meet a human mother who explains that her infant ‘lay and grew in the silken baby-bag beneath my heart.’

Perhaps The Cradle Ship fascinated me so much because I had a vague memory from another book. When I was four, I’d found the big black Ladies Handbook of Home Treatment in my parents’ bedroom. At that stage I couldn’t read but the diagrams were gripping. If you found the right one, then lifted its little flaps, you found a baby in a lady’s tummy. Astonished, I showed my friend Joanna. She must have told her parents and they must have had a word with mine. Though I hunted everywhere, I never found the Handbook again.

The bag in the diagram hadn’t looked silken. There’d been rather more in the way of veins and arteries, and pulpy organs. What’s more the baby was upside down which seemed uncomfortable for it. So two years later, The Cradle Ship’s baby-bag didn’t convince me altogether. But the book as a whole had plenty of action, with Fairy Mother and Poet Father sailing the family wherever they liked.

When I began term one in Standard One, age seven, I was utterly startled when our teacher told us he had written a book. It was Our Street; his name was Brian Sutton-Smith.

When I began term one in Standard One, age seven, I was utterly startled when our teacher told us he had written a book. It was Our Street; his name was Brian Sutton-Smith.

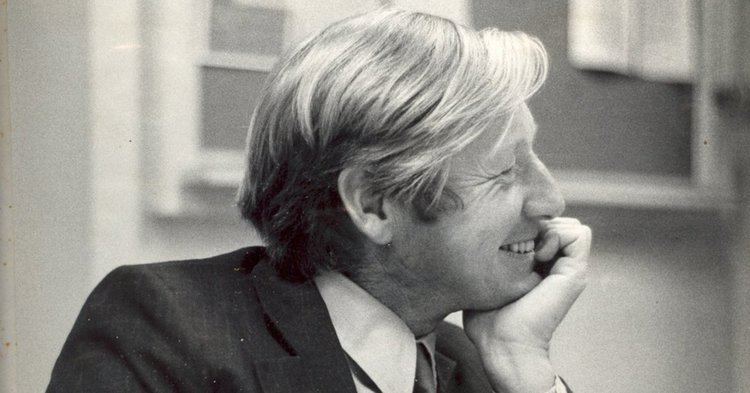

Sutton-Smith was the first New Zealander to get a PhD in Education. He went on to become an international expert in the significance of play in learning, for adults as well as children. For three months before moving to his first job in the USA, he taught at Kelburn Normal Primary.

Even without the book I would have remembered him because he played a guitar in class. It gob-smacked the lot of us.

Our Street. When he told us he’d written it, I was full-alert on the instant. A book – by someone I knew. If we liked, he said, we could take an order form home to our parents and maybe they’d buy one. Good marketing.

A book – by someone I knew. If we liked, he said, we could take an order form home to our parents and maybe they’d buy one. Good marketing.

I leaped at the order form. I dashed home. My parents said yes.

I don’t know whether they’d heard the controversy about Our Street. Critics claimed it encouraged misbehaviour and petty criminality. It was a collection of short stories, first published in the school journal, about boys growing up in Island Bay. They were very much based on Sutton-Smith’s own life with his older brother and their mates. Now they were in a book with a strikingly simple red and white cover, illustrated by Russell Clark. The paper was thick, the signatures stitched, and it was published by A.H. and A.W. Reed.

The main character, Smitty was a boy who got into mischief in streets like ours. Real dirty knees, real arguments, real games, a mischievous big brother who showed Smitty how to sneak into a movie without paying.

Real dirty knees, real arguments, real games, a mischievous big brother who showed Smitty how to sneak into a movie without paying.

My copy of this book is also coming to bits from childhood rereading. But in clumsy printing on the flyleaf is my name and address in Kelburn, Wellington. In awkward handwriting is Mt Eden, Auckland. Beneath that in neat italic script is South Hill, Oamaru.

Should Our Street be reprinted? Probably not. It wouldn’t sell many copies, partly because there are no female characters. But it shouldn’t be forgotten. It was set in our own streets. It was corker. It was affirming. It was beaut.

Bookshops are back open, and need your business! Please go online and buy your favourite NZ books from your favourite NZ bookshop, it will help keep your local community alive.

Barbara Else

Barbara Else writes for adults and children, and has held the University of Victoria Writing Fellowship and the University of Otago College of Education/Creative New Zealand Children’s Writing Fellowship. She has also been awarded the Margaret Mahy Medal. Her most recent novel for children is Harsu and the Werestoat(Gecko Press). She has also writtenGo Girl: A Storybook of Epic New Zealand Women(Penguin NZ), and Tales of Fontania Quartet(Gecko Press), starting with the multiple award-winning The Travelling Restaurant. She also works as a manuscript assessor.