This year’s NZCYA Awards coverage kicks off with the Best First Book finalists! We asked them to tell us, in their own words and with their own spin, about a book that was integral to their childhoods. Here’s what they shared with us.

James T. Guthrie, finalist for Bullseye Bella (Scholastic)

The earliest book I can think of that made a deep and lasting impression on me, which changed the way I thought about books and reading and shaped the choices I would make in my reading and writing for years to come, was Maurice Gee’s Under the Mountain.

It was the first book I can remember reading where I felt genuinely scared from the mere act of reading words off a page. I remember lying in bed, having just finished the chapter where the slithering, slug-like creatures have been lurking outside Theo and Rachel’s window, then having to carefully sneak over to my own window to ensure it was safely closed before leaping back to safety under my blankets.

It was the first book I can remember reading where I felt genuinely scared from the mere act of reading words off a page.

The writing was so evocative. The smell of the Wilberforces (“yellow-green, like bad water in an old forgotten can”), the mysterious, powerful properties of the twin’s stones (“[h]eat came off as if from the element of a stove”) and the absolute heart-wrenching horror when cousin Ricky’s speedboat is smashed to pieces with him inside, consigning him to a watery grave (“floating face down in a sea as black as oil”) – every scene shone brightly and vividly in my mind’s eye.

And, for me, it was something of a ‘don’t-leave-home-till-you’ve-seen-the-country’ book. At that point in my life, I don’t think I’d ever been outside the South Island, having led an idyllic childhood in the Christchurch seaside suburb of Sumner. Although the hills surrounding us (and Lyttleton Harbour itself, just over the hill) were formed by massive volcanic eruptions, the many smaller cones around Auckland that feature in Under the Mountain – especially the symmetrical wonder of Rangitoto – were an exotic wonder to me. To that end, I felt the same sort of awe and wonder that small-town Rachel and Theo did when they arrived in the big city. I still think of Under the Mountain every time I visit Auckland and set eyes on Rangitoto.

It was also the book that started me off on a long love affair with all things fantasy and sci-fi. The premise of the book (spoiler alert: two warring star-faring species have ended up on Earth, with the protagonist Twins being tasked to help the sole survivor of the more peaceful race to help defeat the evil aliens that threaten all mankind) got me searching out the stories of the likes of Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein and Ursula Le Guin. From that, I got into trying to write those sorts of stories myself, locking myself in a room for two weeks over a school holiday to try and write my first book – a (terrible) pastiche of Terry Pratchett’s The Colour of Magic and Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy.

I’ve been plugging away with the writing ever since, and have finally had my first book published, thanks, in no small part, to that initial inspiration I got from Under the Mountain.

Read our review of Bullseye Bella here.

Des O’Leary, finalist for Slice of Heaven (Mākaro Press)

Books have always been a big part of my life. I grew up in a small town, in a home surrounded by books and was always encouraged to read and to think.

Across the creek from our house was the bush, which provided a place for education and imaginative games. At home on winter evenings by the coal and driftwood fire in the living room, my brother and I created our own worlds and stories with the poker in the coals and embers of the fireplace.

I was always a voracious reader. One book that was integral to my growing up was Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, and later the other books in the Earthsea series.

I discovered the writer had created an entirely credible alternative world. The joy that I found was immense and reaffirming to me as an individual. Reading these stories allowed me to suspend belief and enter a world that had been created to share experiences. It showed me that there are other ways of living, other ways of looking at the world.

Reading these stories allowed me to suspend belief and enter a world that had been created to share experiences.

Like many stories, the Earthsea stories told of someone from a simple background who was able to learn to use his natural gifts to grow into his true self. Like any young person with normal dreams and self-doubts to read about this coming of age, this growing into a confident maturity was wonderful. Hey! Even better when he got to ride the dragon at the end. The proof that the prodding of troll caves and dragon dens in the red hot glowing coals and leaping sparks of those winter fires was all true.

Of course, the Earthsea story also carried a warning about actions and consequences. The main character in the Earthsea story had to learn that his actions had the power to harm others so he needed to learn to take responsibility. Like a lot of fiction, it was a safe second-hand experience which showed how we must be responsible for our own deeds. By seeing what a character does, how that can impact on others, by our emotional responses to what we read, we can make more informed choices in our own lives. This was very important to me as a young reader.

I learnt that dragons, in various forms, can be friends or enemies. Demons can guide you or control you. People can befriend or betray you.

Fiction, whatever the genre, is important as it allows this view of different worlds, different points of view, which helps me, the reader, make sense of my own real world.

Read our review of Slice of Heaven here.

Sarah Pepperle, finalist for Art-Tastic (Christchurch Art Gallery)

The other day my mother reminded me that when I was a kid I wasn’t really into reading. I couldn’t be bothered with books that didn’t have any pictures – so many words, so many lines, page after page – I’d rather eat my vegetables. I usually judged a book by its cover and the number and quality of illustrations inside.

Comic books were my go-to; I could spend hours hanging out with Asterix and Obelix or off on adventures with Tintin and my first crush, the bluff anti-hero Captain Haddock. (I think I probably married him.) The awfulness of Fungus the Bogeyman totally delighted me. To encourage me to expand my reading, my Dad would read to me and my sister every night. In this way, we got through the entire Narnia and Little House on the Prairie series, White Fang and Call of the Wild, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Jungle Book, Jock of the Bushveld, Brer Rabbit and many many more.

(Time passes. Now my daughter is ten and she loves reading – but only books with pictures. My son is eight, and his life-interests include trains, cats and the ocean – but not yet books. I find myself repeating history and words, reading to them every night from pretty much the same list of books that my father read to me.)

Around the age of 11 or so, whole worlds opened up when I discovered the escape of young adult fiction. Those years as you leave your childhood behind, something shifts, opens up in you. It’s a space where you think maybe magic can happen – real magic – which I guess is why the YA genre is well-stocked with fantasy. Some of my best memories from this time come from books. Like that time I found a magic ring that made me invisible. Or the cold terror when I realised the witches had seen me. Or when I raced through the night on horseback, and my horse turned to me with fire in its eyes. And of course when the bloodcat stood by my side.

It’s a space where you think maybe magic can happen – real magic…

But one of my most haunting memories was set in a quiet pine forest; my heart racing as I slithered down the needle-covered slope, pursued, a silver crown crammed into my pocket. This is, of course, The Silver Crown by Robert C. O’Brien, the story of Ellen who wakes on her tenth birthday to find a crown on her pillow, goes for an early morning walk and returns to find her house burned down with her family inside – the start of a dark, weird and gripping adventure that dragged me, stunned and tense, through the pages. Although the same copy I read as a child is still in my bookshelf, I’ve not read it again as an adult – only because I would hate for such a spell to be broken.

Brin Murray, finalist for Children of the Furnace (The CopyPress)

I grew up in a comfortable but not bookish household. My dad was offered a scholarship to grammar school but his nan, who was his guardian, couldn’t afford to let him take it up. He left school at fourteen. Nearly twenty years later he had become a police officer and the first in his family to own his own home, and he had acquired his first-born child – me. So he did all right.

He was sporty and couldn’t understand why I liked reading. ‘What are you doing stuck inside?’ he’d say. ‘Get on out there in the sunshine, go play with your friends.’ I never argued with him. I didn’t have the words, didn’t really understand why I thought reading was important.

Our suburb was defiantly barren of arts and culture, but we did have a very good local library, which I visited twice a week. I read fast, absolutely uncritically, and it was a point of pride to finish every book. Now, I give up fairly readily when a book and I don’t get on: books are different and so are people. Then, I never did. Grim perseverance triumphed.

I can remember sitting on our garden wall and wishing with a passion that Pippi Longstocking, or the Moomins, or Just William would happen by. Real life was boring, I thought. So boring, that at seven years old my friend and I decided to run away to Moominland. Luckily, my co-conspirator’s mum thwarted our plans.

On my ninth birthday, a friend of my mum’s gave me Emma by Jane Austen. I dutifully read it and the grim perseverance thing kicked in big time. I didn’t understand it. I hated Emma, and couldn’t understand why this horrible girl was the main character. I wanted her to be good from the start, so I could root for her. She wasn’t.

I wanted her to be good from the start, so I could root for her. She wasn’t.

It’s an experience that I always remember, because it taught me something crucial: that reading the words is the shallowest part of the reading process. It’s necessary, but completely unrelated to deeper understanding. Emma was too emotionally complex and the subtleties of the wit were utterly lost on me. I wasn’t developmentally ready for that book. It could have put me off Jane Austen for life. Fortunately, around six years later I read Pride and Prejudice and found it hilarious. Emma subsequently became one of my favourite books ever.

One day the librarian said to me: ‘You need to be reading more widely. You’ve been reading these kid’s books for years. You need to challenge yourself.’

I resented that. They were my easy reads, the ones I went back to again and again. But after the librarian told me that – and organised my membership of the adjoining adult library – I was too embarrassed to get out my old favourites when she was there, which was most of the time. She was right of course – although I now believe that it’s also okay for kids to go back to old favourites and read them time and again, like slipping on an old pair of comfy socks. All reading is good, and comfy sock books are great. They nurture a love of reading.

Anyway, I trudged to the adult library next door. I started reading best-sellers, and many were disturbingly gruesome. I still remember them today, so their impact at the time must have been shocking. A tortured woman buried to her neck in sand; an impaled baby thrown onto a burning roof; an army private disembowelled by a sadistic superior officer. So, there is danger to a whole lot of uncritically devoured genre fiction: tweens don’t sleep at night, and maybe develop a terrifyingly dark view of human nature.

On the other hand, because I was an enthusiastic reader with no real understanding of book categories, I gradually mixed up my genres with what I later understood were classics. There must have been a very good librarian in that library, I think now. The range of books was eclectic and multicultural – in that area, at that time, I imagine we young readers were very lucky.

There must have been a very good librarian in that library… The range of books was eclectic and multicultural – in that area, at that time, I imagine we young readers were very lucky.

And if I could talk to my dad now, and discuss with him the merits of playing in the sun versus reading? Well, in an ideal world kids get to do lots of both…

But I would tell him that reading is incredibly important. Reading is entertaining, it is fun, but crucially it opens your eyes to the world. Reading is condensed information and deep understanding. If you have read the Victorian novelists, and go on a university level psychology course, you will find very little that is new or surprising. It’s all there, in those novels: a depth of understanding of character that dry academia can’t impart in the same way. Novels go deeper than any intellectual understanding possibly can: they deliver the soul.

Thank you, Old Redbridge Library.

Read our review of Children of the Furnace here.

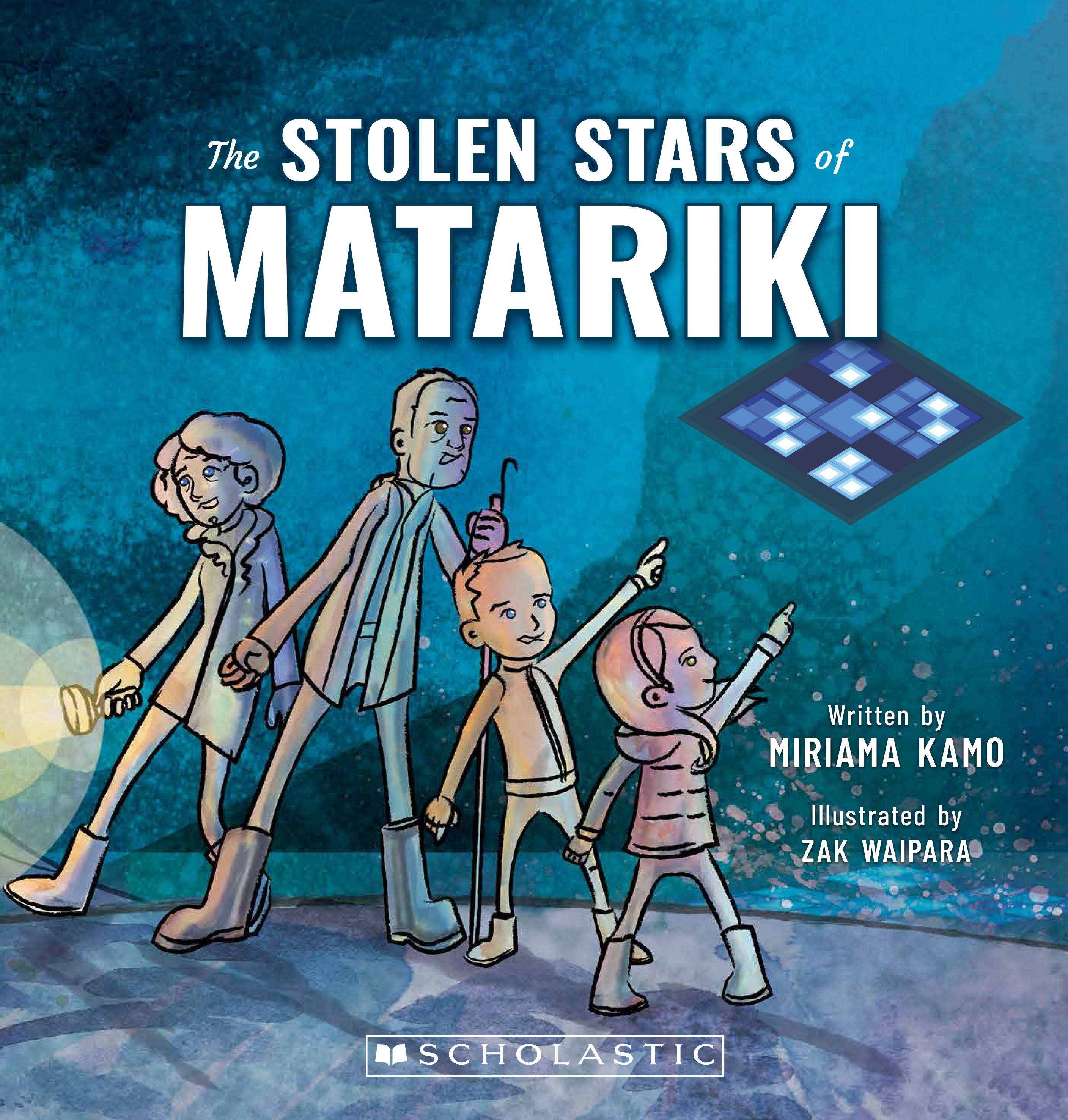

Miriama Kamo, finalist for The Stolen Stars of Matariki (Scholastic NZ)

Miriama may be a first time author, but in her capacity as a public figure and beloved broadcaster, she has written about her book-loving childhood for us before! Here’s an extract from that piece – you can read the whole thing here.

When I think of Pounamu, Pounamu, I still feel transported, as if I’m running through dry, yellowed grass, standing on the sidelines of a loud rugby game, having my head shucked by an older cousin, and being growled by a loving Nanny…

I realise how important Kiwi writing was to my formation as a reader. What led the way to Pounamu, Pounamu? Well, yes, there were myriad young reader books. I was a total bookworm. I was compelled to read. I’d spit out books like a tennis ball machine, barely registering their titles. I stopped most days at the library on my way home from school. I loved Enid Blyton, for example; I suspect I’ve read most of her works. But, as a family we loved comic strips: Andy Capp (good lord, I never knew how inappropriate it was), The Wizard of Id, Blondie, Charlie Brown. And we had every Footrot Flats book.

I was compelled to read. I’d spit out books like a tennis ball machine, barely registering their titles.

My parents had overly satisfied bookshelves, tonnes of books weighed down every shelf, and every room had at least one shelf. But we never bought books new; we got them all from libraries, from second hand sales, from friends and family. Except for Footrot Flats. When a new edition hit the shelves, it was immediately earmarked for whomever had the next birthday…

Maybe this laid the path to Pounamu, Pounamu, capturing so hilariously the desperation and satisfaction of farming life, then so central to the Kiwi self-image. Pounamu, Pounamu evoked another way of life, equally familiar, actually more familiar. It spoke to my own childhood, packed full of joking cousins, big family meals, the childish want for more, to fit in, to make people proud, the sense of wanting approval while expecting rejection from the world. But more than that, it validated the country we live in. It said ‘aren’t we funny, silly, angry, brave, loving, and wanting.’ And at 12 or 13, the age that we look to understand who we are and how we fit in, it told me it was okay to be all those things.

Read our our interview with Miriama on The Stolen Stars of Matariki here.

The Stolen Stars of Matariki

By Miriama Kamo

Illustrated by Zak Waipara

Published by Scholastic NZ

RRP: $17.99