How many children’s books have you read that tell stories of family violence and abuse? Today author, speaker and survivor of family violence, Tim Tipene, argues for more books that show the reality of life for far too many children in Aotearoa and beyond.

Content note: this essay contains descriptions of child abuse and family violence.

As a child I grew up in two worlds. In the first, I had to deal with the anger and misplaced hurt of the adults in my family. I was beaten and abused on a daily basis. Not for any wrong doing, but just simply as an outlet for my parents’ projections – parents who had been abused themselves and were locked into the cycle of violence. They were hurt and damaged people.

Then there was the second world where everyone pretended that it wasn’t happening. Where the smell of urine on me from my constant bed-wetting went unremarked, along with the bruises and marks on my body. Where my inability to learn at school due to my high levels of anxiety and fear from being traumatised, meant that I was simply a failed learner, and a bad kid who was often in trouble.

I found it difficult to relate to others. The children’s books I read were whimsical and happy, and spoke of a world I had no knowledge or experience of. It was as though I was a foreigner in my own country.

The children’s books I read were whimsical and happy, and spoke of a world I had no knowledge or experience of.

Mine was a lonely world, living with the secrecy of abuse. Much of the power that abuse has over a person is in the secrecy, or, more to the point, the untold truth. Because many did know about my abuse or chose not to see it, either because they didn’t know what to do about it, or were too afraid to approach it. So nothing was ever said.

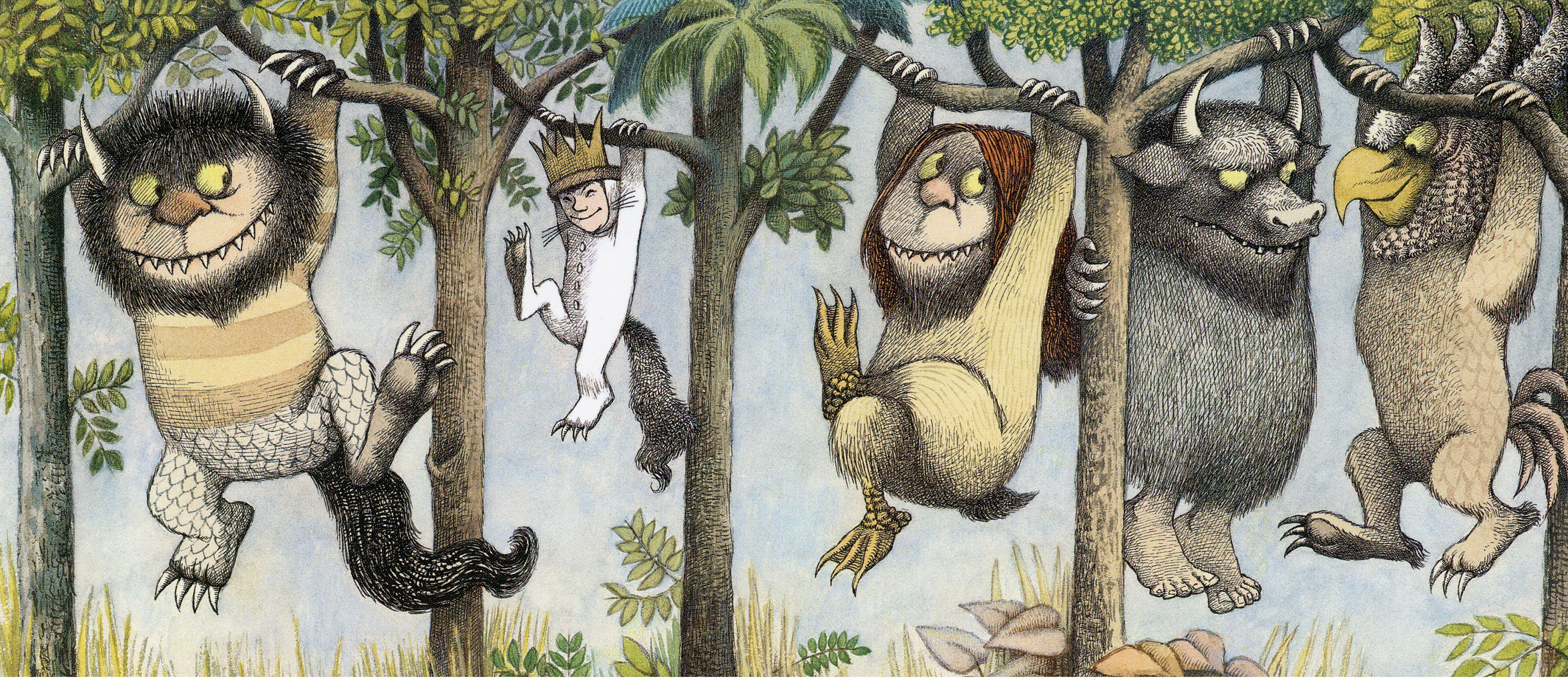

I didn’t do well at any of the subjects at school. I usually had to attend special classes for learning during normal class time, including one for reading. I never connected to any book until one day a title caught me. It was Where the Wild Things Are, by Maurice Sendak.

The title made me sit up. I knew where the wild things were. They were in my home, they were in my family, they dominated my life. I instantly felt a connection to this book.

As otherworldly as it was, it was the first book to speak of my reality. The reality of monsters and anger. In some small way through that story my experience, and thereby my existence had been validated. Because to deny the abuse is to deny the person experiencing that abuse.

When one is experiencing violence and abuse it is that experience that trumps all else. There were times where I wasn’t sure if I was going to be alive the next day. Maths, school work, none of it seemed important as mortality.

Where the Wild Things Are opened up my world. I didn’t feel so alone anymore. My experience was there in print. Later, monsters and anger were themes I revisited with my own book, Taming the Taniwha, in 2001. It was also a theme in my teenage novel, Kura Toa Warrior School.

When Kura Toa was published in 2004 it went largely unnoticed. Apart from a couple of nice reviews it was largely ignored within the literary world. However, 24 years on, Kura Toa Warrior School hasn’t stopped selling. In 2013 it was put on as a stage production by Bay of Islands College with tremendous success. The feedback about this novel is that it is real. It speaks of family violence, and kids can relate to it.

Children’s books that deal with family violence and abuse are not common. While books starring orphans and mistreated children are universal and best-selling, books focusing on child abuse and family violence tend not to be. It is safer in story if the perpetrator of abuse and violence is coming from outside the immediate family and not from within, thereby protecting the sacredness of family, and of the mythical idealistic figures of mother and father. When one describes cracks in a family people can get uncomfortable because it can be too close to home.

While books starring orphans and mistreated children are universal and best-selling, books focusing on child abuse and family violence tend not to be.

We like to protect our children from the harsh realities of life. We fill their worlds with fairies, the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus. There have been schools that didn’t want to purchase my book Haere: Farewell, Jack, Farewell as it is about death, and they didn’t want to go there with the children. It is the same with abuse and family violence. Many simply don’t want to go there. But at what cost? In being too afraid and uncomfortable to speak about family violence and abuse we become enablers. We take the side of the perpetrators by protecting them with our silence. We empower them.

It is only a matter of time before another child killed by their family is the main headline in our news. The reality is that family violence and abuse is the daily life of a huge number of children in New Zealand.

The truth will set us free.

We need children’s books about family violence and abuse to acknowledge the reality for so many children. We show them that they are not alone and offer hope that there is a way through. We relieve their guilt and shame from being abused, from being part of a violent, imperfect family. We help them to unravel the complexities of the issue, and in turn they question what they see around them. This is questioning they will continue to do as they grow into adults, and think about what sort of adults and parents they are going to be.

Traumatised kids need maps, the maps found in stories. We now know that trauma changes the way a developing brain grows. I didn’t know how to interact and behave in the world. All I knew was what I grew up with. As a young man I sought out books that would help and show me how to function in this world. It was the lack of such books for children and young people that got me writing them myself.

Research shows that children who read widely are more empathetic towards others. In reading about family violence and abuse children outside of these experiences are able to understand and relate to some of their classmates better, and have an insight into their lives, while reflecting on their own. At the same time it opens up discussion around parenting, the processing of emotions and the cause and effect of behaviours.

This is not to say that children should be given graphic details. It doesn’t take much to convey the message. I often share an incident that I had at school where I showed a classmate a lump under my arm as a result of a punch from my father. The story follows the boy’s reaction and how he told the teacher, and the kind way in which the teacher addressed it, and how it became a pivotal point in my life.

I have written my own childhood out as a novel for children based on my talks in schools, where I demonstrate that there is a way through family violence and abuse, and show that the cycle can be broken. The novel was the result of many requests from schools to put my story into book form for children that could be used in the classroom. But as yet no publisher is interested in publishing it. Publishers are reluctant to publish stories about family violence and child abuse – a reflection of the market being reluctant to purchase them. But such stories are essential and required in addressing this social issue. Perhaps funding could be made available to entice publishers to publish such stories. Perhaps it is a task for Learning Media, or perhaps it requires self-publishing with an external editor.

Publishers are reluctant to publish stories about family violence and child abuse – a reflection of the market being reluctant to purchase them. But such stories are essential and required in addressing this social issue.

When I am asked about culture I say that I was raised in two cultures, New Zealand European and Māori, with connections to Ngāti Kura and Ngāti Whātua. But first and foremost, the culture of family violence and abuse has had the greatest impact on my life. As a result I continue to write books about it, speak about it, and I continue to run Warrior Kids, a programme I created to address family violence and to support children with empowerment, self-control and self-regulation. I have sometimes wondered what my life would have looked like if I had not been abused, wondered what I would be doing instead. However I am reminded of what I have done, the impact that it has had, and of the vital importance in speaking up about family violence.

We know where the wild things are, so let’s stop pretending. Let’s get writing about it, let’s get reading about it, let’s get talking about it. Because we can cause change.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Tim Tipene

Tim Tipene (Ngāti Kuri, Ngāti Whātua) is an author, speaker, educator, and survivor of family violence. He is the award-winning author of ten children’s picture books and junior novels including Kura Toa, Haere, Taming the Taniwha and 2016’s Māui: Sun Catcher. A pioneering youth and self-defence counsellor, he leads the Peace Masters and Warrior Kids programmes.