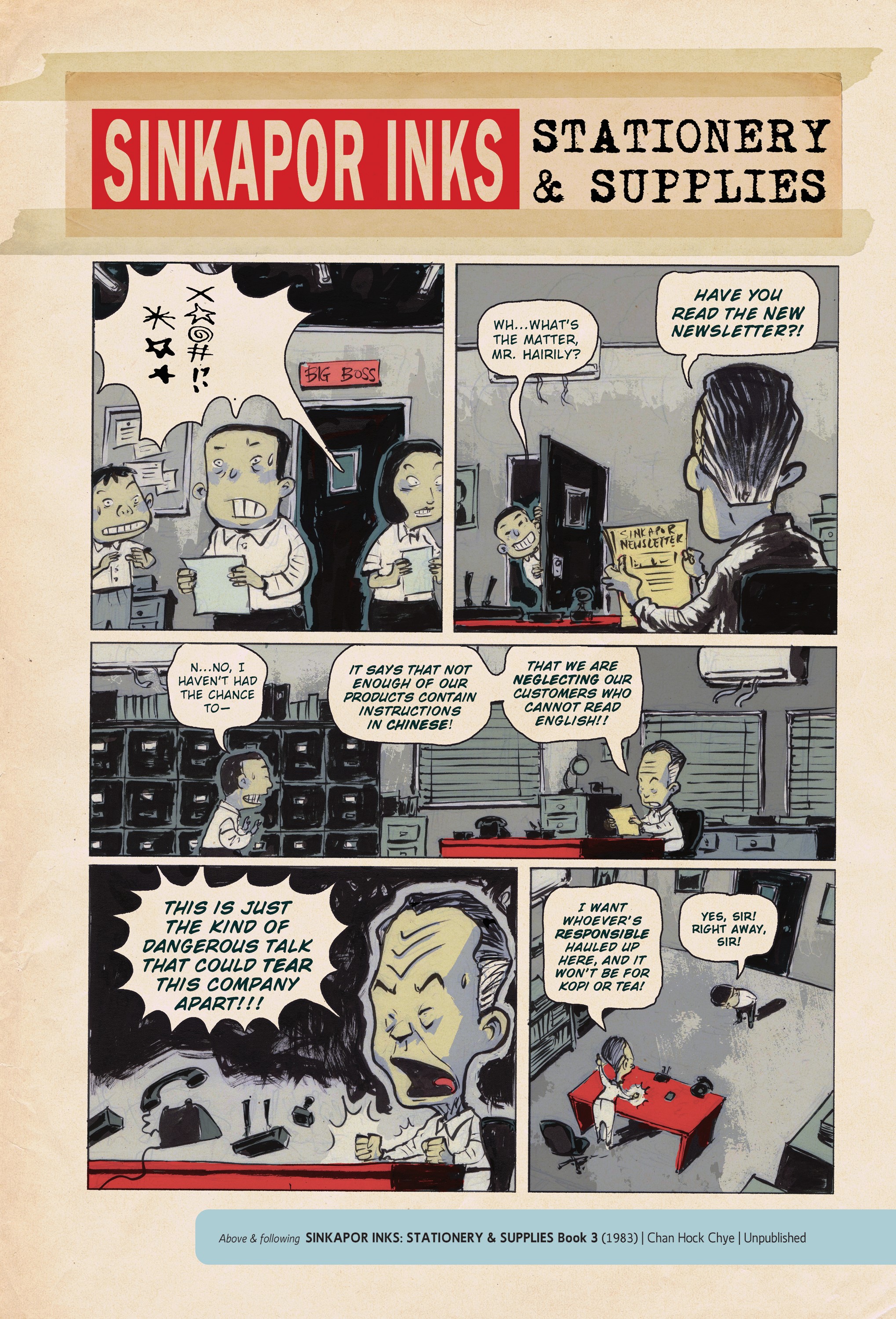

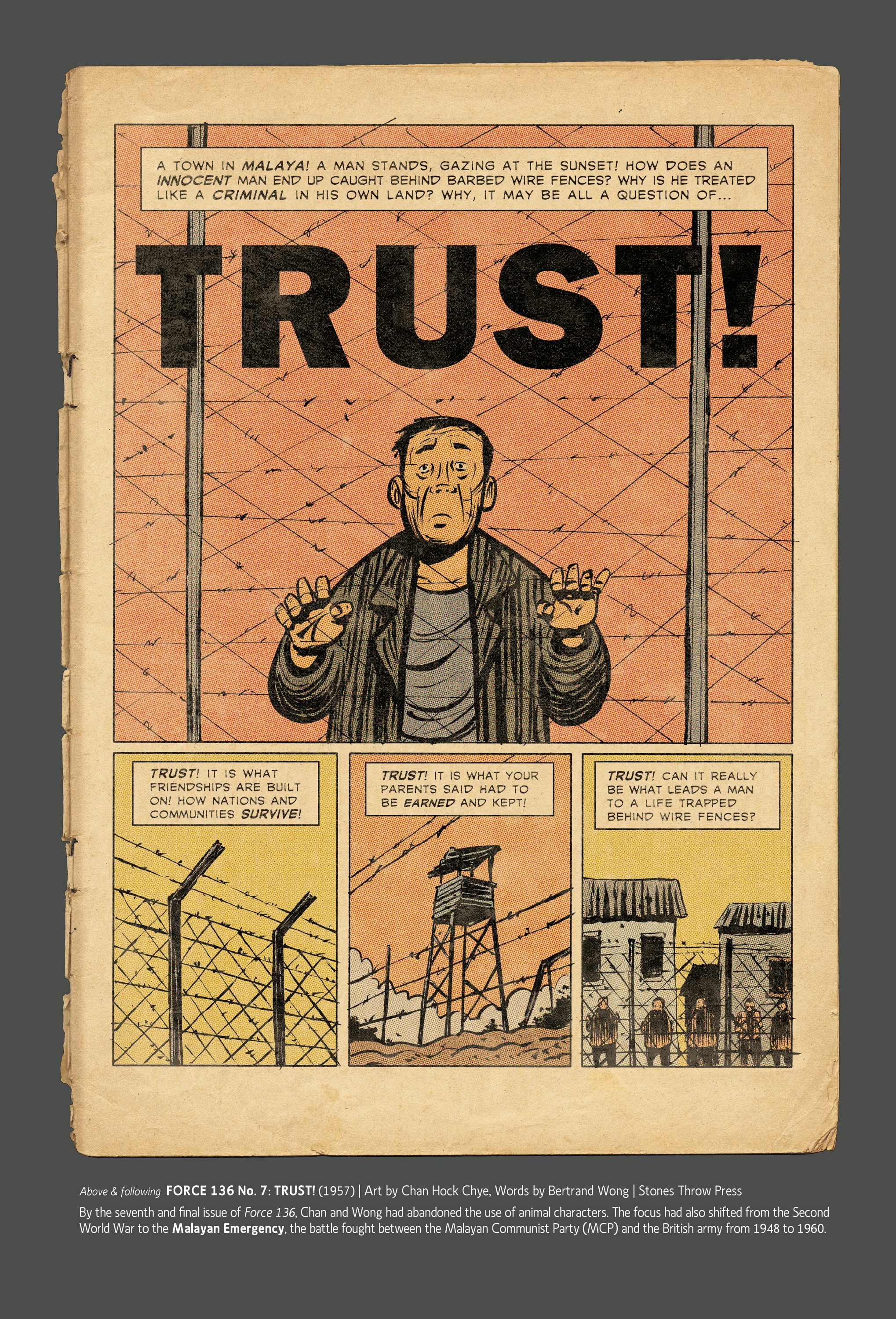

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye tells a tale encompassing stories strewn over decades of the creation of Singapore. The apathetic yet significant cartoonist, Charlie Chan, has documented the era of agitated independence that the Lion City faced at different times during its history. Richly illustrated with differing artistic styles, the graphic novel captures the quiet space of political turbulence and personal hardship, introducing Charlie as the hero Singapore truly needs, fictional as he might be.

This book is the masterpiece of Sonny Liew. His magnum opus, it went on to win numerous accolades and the hearts of its readers. Liew was a three-time Eisner Award winner for, as well as being the first Singaporean to lead the charge on the Eisner nominations that year. Besides winning the Singapore Literature Prize, he also won the Book of the Year accolade at the Singapore Art Awards in 2016 for his creation. Sonny was also awarded the prestigious Pingprisen for Best International Comic in 2017, truly cementing his place as one of the finest international artists.

I had the privilege of interviewing Sonny in advance of the New Zealand Festival, where he will be making an appearance on the 10th of March at the widely anticipated Writers and Readers event.

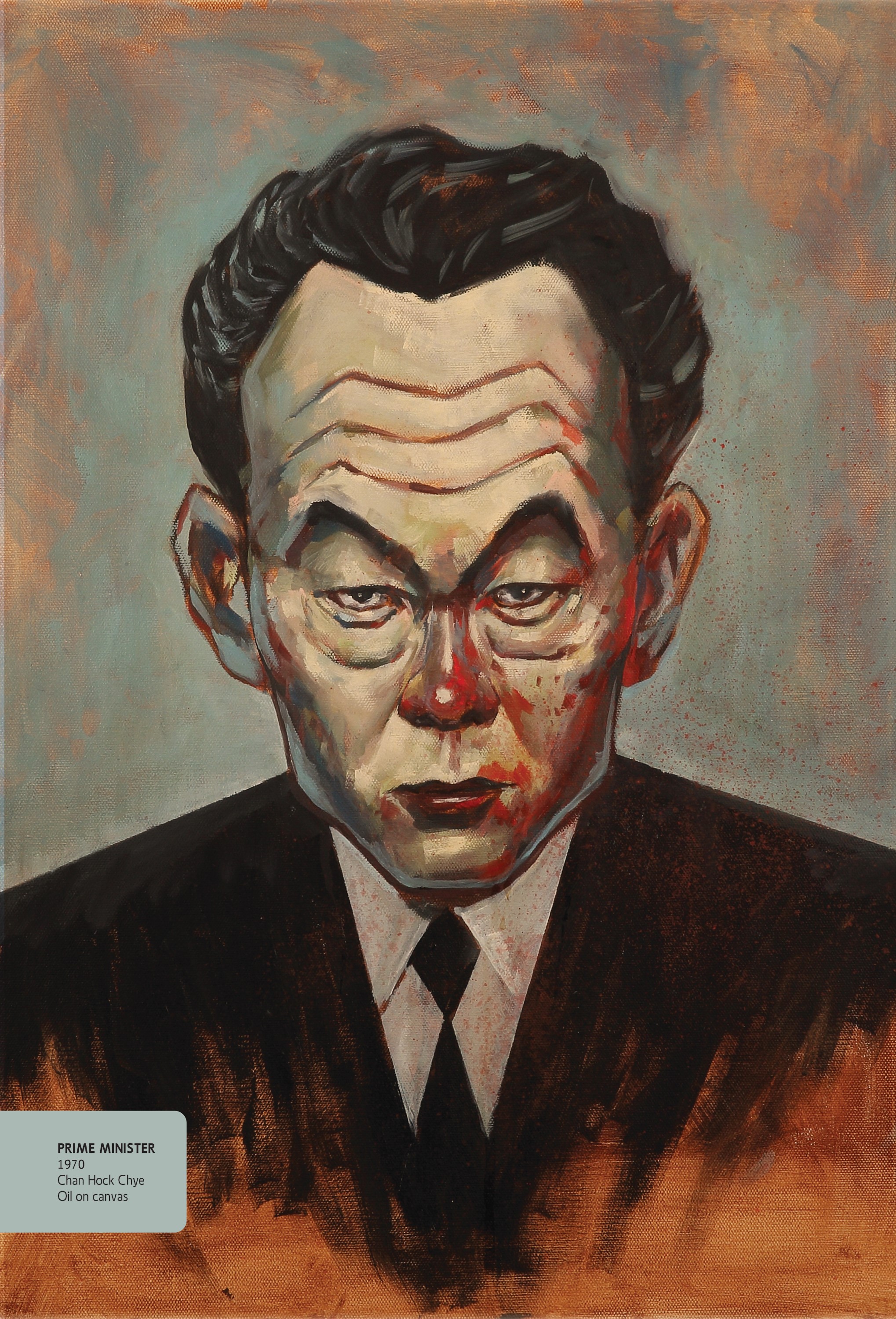

Your award-winning graphic novel The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, provides the foundation of modern history in Singapore through a personal narrative. Singapore’s narrative has been pushed upon the country through media and is very rarely opposed effectively. Your book offered a factual and inclusive vision of its history of ‘tough love’. I personally appreciated your candid exploration of Mr Lim Chin Siong’s story. When did you realise an interest in creating this novel and who/what was your biggest influence in bringing it together?

I’d thought of the basic premise for the book some years back – but at that point there didn’t seem to be any realistic hope of a publisher anywhere giving me enough of an advance to work on a book about Singapore. To some degree it was a difficult book to explain as a concept – in some ways you had to actually make the thing to make it clear what it was. It took a Series of Unexpected Events to make the project halfway feasible, and even then obstacles would get thrown in the way every now and then.

It took a Series of Unexpected Events to make the project halfway feasible, and even then obstacles would get thrown in the way every now and then.

The initial spark came from reading actual books about comics history – getting a sense that you were always learning about general history when you were reading about comics history gave me the idea that the thing could be flipped on its head. That aside, the tactile feel of old comics, the formal experimentations of authors like Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes, and much more all fed into the book.

The distribution of historic and current events are commonly constrained to the limits of hefty books and snappy articles. Do you believe that it is harder to get your message across a medium that is viewed by many, in my opinion falsely, as trivial? When was your earliest experience where you learned that illustrations had power?

The sense of comics being a trivial or juvenile medium can actually be something of an advantage – we come at it with our guard down a little, our approach shaped by the nostalgia of reading comics as kids. So as much as it’s important to try to get across the idea that comics are a medium like any other, not a genre; to an extent you can’t really escape from the real world historical roots of comics, and maybe can even turn those roots into an advantage.

The sense of comics being a trivial or juvenile medium can actually be something of an advantage – we come at it with our guard down a little, our approach shaped by the nostalgia of reading comics as kids.

I don’t think there was ever an eureka moment for me – drawings, comics, illustrations were things I grew up with surrounded by, thanks to my parents buying me and my sister comics, as well my grandpa’s library collection of all sorts of books. I knew that illustrations and books were powerful from a very young age.

What do you believe are the ethics of writing about historical figures?

I suppose it depends on your aims. If you’re trying to tell real history, you’d have to do your best to gather all the information you can to give a fair interpretation of their lives.

If you’re using their stories as springboard to develop fictional accounts there’s much more leeway to things. But new ways of thinking and looking at things will always appear, which is probably why every decade or so you’ll new biographies or histories of everything from Churchill to the Opium War.

Before The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, you worked on quite a few projects, my personal favourites being Liquid City and Wonderland. What has been the most rewarding project in your professional career — in or out of comics — and why?

At this point it would have to be The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye – as it is my first attempt at both writing and drawing a long-form narrative. It’s the kind of book I’ve always wanted to do, something you can pour all your thoughts and ideas into.

It’s the kind of book I’ve always wanted to do, something you can pour all your thoughts and ideas into.

A lot of my other projects involved collaborations with writers, which have their own attraction in terms of learning the craft and how others tell and construct stories. But there’s really nothing quite like working on a book of your own. By the end of it I felt a little emptied out, and the past couple of years have been spent to some extent rebooting and trying to find new ways of thinking about the medium.

After attending Victoria Junior College in Singapore, you went on to read philosophy at Cambridge University. Do you find that your tertiary studies in philosophy give you a fresh perspective on writing comics?

The kind of philosophy we did was rather academic, so I’m not sure there are clear or direct links with the comics. The one thread that I can think of is the whole process of doing research for essays – that probably carries into the kind of research you need to do for books like Charlie Chan … a lot of reading, digesting information and trying to produce something at the end of it that provides a fresh take on things.

… a lot of reading, digesting information and trying to produce something at the end of it that provides a fresh take on things.

What’s the most important “big idea” that you’ve learned in life – in or out of comics – and why is it important?

I’m not sure there are ideas like that, outside of TED talks. Everything is always in flux, equilibriums are temporary, so it’s maybe more about always being open to new ideas rather than relying on one big one to deal with all the myriad challenges we’ll face in this thing we call life.

You can see Sonny in person in Wellington this weekend on Friday 9 March at 4.15pm New Zealand Festival, and at Saturday 10 March, 5.45pm, at the NZ Festival Writers & Readers Festival

Niruthmie Pallawala

Niruthmie Pallawala is a Year 12 student at Wellington Girls College and lives in Wellington, New Zealand. She has a vested interest in the melting pot of culture that is Wellington and is a budding human rights activist in the Amnesty International Club, and loves volunteering at the Mary Potter Hospice in her spare time. She is fascinated with all things scientific and adores the field of neuroscience - especially on how it decides our perception of the world as an entity.