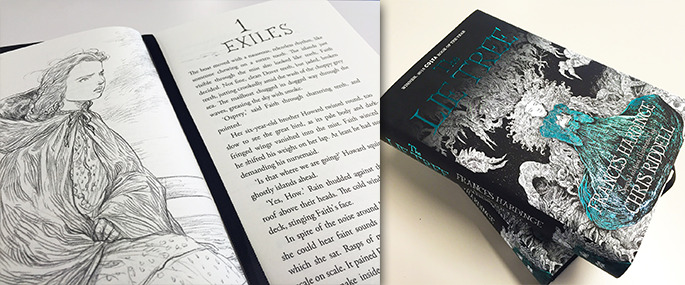

British writer Frances Hardinge is living proof that books for kids can be as good as books for adults: her last YA novel, The Lie Tree, won the Costa Book of the Year in 2015, beating out serious science biographies, acclaimed poetry collections, a novel by Kate Atkinson and more. Kiwi writer and Hardinge fan Elizabeth Knox leapt at the chance to interview her ahead of her appearances at the Auckland Writers Festival on 20 and 21 May.

Elizabeth Knox: Francis Spufford gave me Cuckoo Song when I was in England in 2015. I read it on the plane home. When a writer who likes your work introduces you to another writer whose work they’re sure you’ll love as much as they do, it’s almost better than having made the discovery yourself. I’ve read everything now – except Gullstruck Island. (I’m in the frame of mind, with winter coming, where I want to save a few books by reliably transporting and engaging writers so that I might pull them up over my head on those very cold Sundays of July.)

I’m fascinated by particular virtues you have as a writer, and curious about several of the figures in your carpet—your repeated motifs. (The word motif doesn’t seem to express a writer’s need for, or joy in, the things they do again and again, and develop throughout a writing life.)

I love your 11-something heroes. Mosca Mye, Neverfell, Ryan, Triss. Children of an age where they’re figuring out how their worlds work, without an adolescence’s fretfulness about themselves, and how they might belong. They’re not closely watched, and have a lot of not always welcome independence. I’m wondering if you’d like to talk about the freedom a writer gets from having a protagonist of this age – especially a writer who is writing for readers of all ages, as I think you are.

Frances Hardinge: I’m sometimes asked whether I find such writing for children confining or frustrating, and the answer is definitely ‘no’. I don’t tend to dumb down much, and I’ve got a lot of respect for my younger readers, and their ability to handle dark and complex plots, so there’s nothing to stop me telling the stories I want to tell. In fact, it’s often possible to get away with more genre-crunching and experimentation when writing children’s and YA books, so it’s actually quite liberating.

I’ve got a lot of respect for my younger readers, and their ability to handle dark and complex plots …

As far as I’m concerned, my books are ‘for’ whoever enjoys them, regardless of their age. However, most of them were written with the twelve-year-old version of me as the imagined reader. It’s an age I remember quite vividly, and one that continues to fascinate me. It’s a time when you’re underestimated and have little control over your life, but where you’re starting to unpick a lot of what you’ve been taught, and are starting to question and challenge. Your old self no longer quite fits, and your understanding of the world around you begins to crack and shift.

Furthermore, if my main character is eleven or twelve, there’s less expectation that I’ll involve them in a romantic subplot. There’s nothing wrong with romances, of course, but they don’t fit in with every story.

E: Story and plot in your novels seem as much determined by geopolitical situations (which makes it sound as if I’m not talking about vast caves full of artisan guilds producing luxury goods, or towns where people have to pretend to be dead according to the hour of the day). Your plots are determined by this social and political stuff, and by the principal characters’ internal pressures. What happens often plays out according to how the protagonists accept or resist what’s thought or said about them by others. I’m thinking here of how much Faith values the intellectual connections she believes she’s made with her father. Or how Triss is guided by ideas about the ways in which a daughter or older sister should behave, and so changes everyone’s fortunes. Or even how the highwayman in Fly by Night turns in real life into the hero of the lying epic he’s forced out of a poet at gunpoint. Is it fair to say you’re a writer who is interested in how what happens in the story is shaped by the way people understand themselves? This seems both a plot driver, and of the moral heart of your work.

F: I only truly understand my characters once I understand the setting, their history, their upbringing and the things they’ve been taught to believe. All of my characters are shaped by their world, even those that ultimately decide to rebel or change it.

There’s a rather unpleasant character in Fly by Night who says that if you want to understand somebody well enough to manipulate them, then you need to know what they want, what they fear, and what lies they tell themselves. I’m fascinated by blind spots, both personal and communal, and the untruths or injustices that people will accept because of habit, consensus or rationalisation.

Given the way that our sense of identity tends to be based on feedback from the outside world, it seems fairly natural that a character’s journey of self-discovery should also involve learning to question the world around them. The character develops the ability to judge their judges, and this lets them see themselves in a new light. This happens in most of my books.

I suspect a lot of us have a lurking anxiety that we’re basically a patchwork of borrowings …

In Cuckoo Song, of course, a character is literally fashioned from borrowed oddments and trinkets. The poor character is left wondering whether there is any part of her that is really, truly her. (I rather think there is.) I suspect a lot of us have a lurking anxiety that we’re basically a patchwork of borrowings – the things we’ve been taught and have internalised, our experiences conditioning us to act in certain ways, our schooling, subtle messages from the media, the influence of our parents, other people’s criticisms and validations, and quotes and thoughts that we think of as ours but which we’ve unconsciously picked up elsewhere.

E: There are moments in the books—Mosca’s understanding the implications of her reclassification as a Nightling, Triss when she begins to fall apart, Faith’s experience of her father’s shame—that are more than just suspenseful jeopardy, they are terrors of a kind. How do these moments come to you, and how do you come at them when you’re writing them?

F: The terrors are a fundamental part of the books, and when I’m writing those parts, I usually feel that I’m closer to the story’s emotional core. If you will pardon a rather disturbing image, it feels as though I’ve managed to drill through the bone and hit marrow.

Uncanny fear has always had a galvanising effect on my imagination, ever since I was a little girl reading ghost stories and murder mysteries. A sense of threat or spookiness was never enough, though. There had to be an extra emotional twist to the fear, something to strike a deeper chord the way the darkest fairytales do.

Uncanny fear has always had a galvanising effect on my imagination, ever since I was a little girl reading ghost stories and murder mysteries.

E: Does either of your two kinds of books excite you more? Those with a recognisable mythology at their heart, like Cuckoo Song or Verdigris Deep? Or the ones set in intricately invented other worlds, like the Mosca Mye books?

F: To tell the truth, I don’t think of my books as dividing into two neat categories! It’s true that some are set in imagined worlds, whereas others have fantastical plots set in this world, either in the past or the present. However, my invented worlds tend to be fairly different from each other.

The Fractured Realm, in which Mosca Mye has her adventures, is bizarre and whimsical, but doesn’t contain anything magical or supernatural at all, unlike my other invented worlds. Also, the Fractured Realm is based partly on early eighteenth-century England, which allowed me to have fun researching highwaymen and smugglers, window tax, marriage houses, auctions by candle, and much more – so the Mosca Mye books have more in common with my two historical fantasies than you might think!

Usually, the ‘type’ of book that I usually want to write is something that feels different enough from what I’ve written before …

E: I feel that you’re attracted to stories about aftermaths. I’m thinking here of The Lie Tree and Cuckoo Song. What is it that attracts you to stories about or set in aftermaths?

F: I’m fascinated by periods of transition – upheavals, revelations, revolutions. When the world changes, it doesn’t do so neatly, and if it does so quickly there are usually consequences. I’m always suspicious of any fictional rebellion or battle that is depicted as solving all problems, aftermath-free.

I’m always suspicious of any fictional rebellion or battle that is depicted as solving all problems, aftermath-free.

If you’re a historian or a writer, it’s easy to focus on the big, dramatic events. But by looking at the aftermath, you’re able to fully understand what those events mean.

A number of my books feature revolutions, and all of them have aftermaths, rather than neatly solving everything for everyone for evermore. The uprisings tend to be followed by messy negotiations, and compromises that don’t really please anybody, but could be a lot worse. The second Mosca Mye book, Twilight Robbery, involves all the knock-on effects of the rebellion in the first book, and is basically a story about consequences. The main characters are confronted with all the disruption and fallout that the uprising caused, and have to decide whether they are still happy with their previous actions. (In the end, they decide they are.)

E: Myrtle Sunderley’s cold and ruthless practicality seem almost as heroic as her daughter Faith’s passion and energy. I don’t know that anyone would say they’re both feminist heroes, but there is much to admire in Myrtle, and I’m wondering how you feel about her.

F: I’m actually rather fond of the dreadful and manipulative Myrtle. She will flirt, scheme, lie, and play the air-head, but then again she is fighting for her own survival and that of her children in a world where all the odds are stacked against her. Although she doesn’t have her daughter’s academic prowess, she has her own ruthlessly practical intelligence, and a very formidable will.

Rebelling against society is hard, sometimes to a crippling degree. So while I deeply admire those Victorian women who did defy convention, I also have plenty of sympathy for those who didn’t rebel because of the impact it would have on their lives and families, or who believed in society’s codes and soldiered on within them as best they could, or who subverted the system like Myrtle in order to get by.

E: Lastly as a reader with appetite, with only Gullstruck Island in reserve, I’d like to ask do you know what’s next?

F: I’m currently working on another YA historical fantasy, set during the English Civil War. It involves an ancient family with sinister inheritance traditions, gold smuggling, spies and a very angry, very dead bear… .

Elizabeth Knox

Elizabeth Knox has published twelve novels, three autobiographical novellas and a collection of essays. Her best known books are The Vintner’s Luck, and The Dreamhunter Duet (Dreamhunter and Dreamquake). Her latest are Mortal Fireand Wake. Elizabeth lives in Wellington, New Zealand with her husband, son, and three cats.

Photo by Grant Maiden