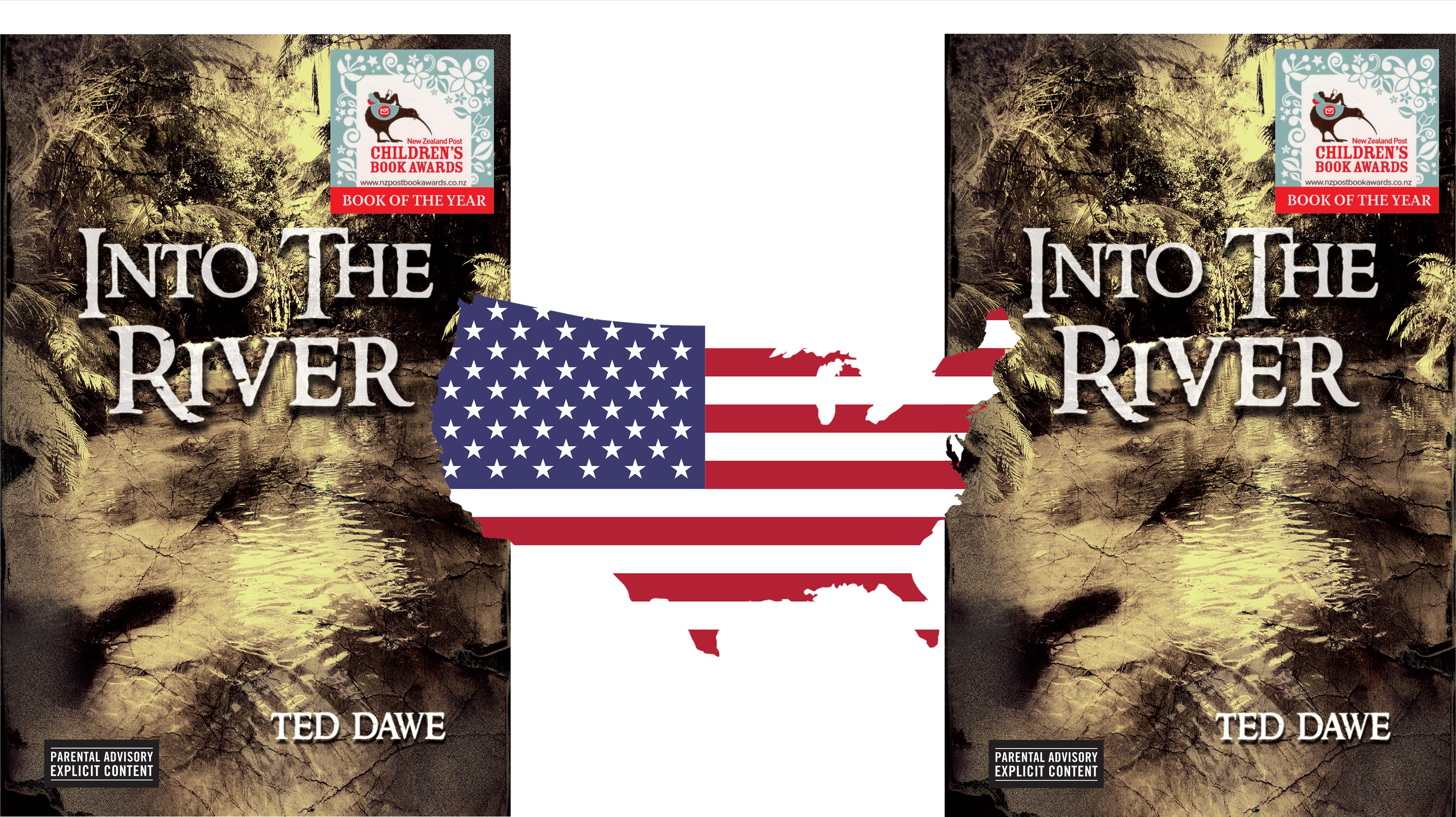

Soon after the 2015 banning controversy in New Zealand, Into the River was purchased by US publisher Polis Books, and will be released in paperback in the US this month. We had YA writer and renowned American book critic Michael Cart give us an international view of the book. Is it as risque as all that?

Libertad! It’s ironic that a book which concluded with the Spanish word for ‘freedom’ should have been subject to suppression – suppression that, for a time at least, denied people the freedom to acquire or even, perhaps, to read it. And yet, of course, that is exactly what happened to Ted Dawe’s award-winning novel Into the River. News of the controversial case quickly reached us here in the United States, reminding us of the hue and cry that visited the award of England’s Carnegie Medal some years ago to Melvin Burgess’ novel Smack. In any case, the controversy was noted in a number of the reviews of the book, which appeared when it was published here in 2016 by Polis Books.

Noticed in all the major journals, the reviews were unanimously favorable, one calling it ‘a tough, plausible culture-clash, coming-of-age story’ (VOYA). Another, hailing the novel’s ‘compassionate depiction of the teen’s choices, good and bad,’ concluded: ‘it will give this significant appeal for fans of character-driven novels.’ (Booklist). Several reviews were a bit more cautionary: one, for example, acknowledged what it called the book’s ‘frank, often grim representations of violence, drug use, and fumbling teen sex …’ (Kirkus Reviews) but none failed to recommend the book for purchase. However, the targeted age of its prospective readership varied a bit. Thus Publishers Weekly recommended it for readers ‘ages 13-up’; School Library Journal recommended ‘Grade 8 up’ (i.e., 14 – up); Kirkus Reviews recommended it for ages 14 to 18; VOYA recommended ‘ages 15 to Adult’; and Booklist recommended it for ‘Grades 10-12’ (i.e., 16 to 18).

These are purely recommendations, of course. There is nothing formal or ‘official’ about them. Individual librarians will make individual choices based on local interest and needs. There is no national system here of vetting of any sort and, perhaps accordingly, New Zealand’s system seems to most of us a bit, well, arcane and seemingly punitive (e.g., fines and restrictions upon circulation of the book).

This is not to say there are no book challenges here in the U.S. There are, of course, though they are typically localised. That said, there are, nevertheless, national, private organisations like Family First that do encourage local chapter members to challenge individual titles. Indeed, three of my own books have been subject to such challenges. However, to the best of my knowledge, none has yet been targeted at Into the River.

In the context of contemporary American young adult fiction, there is nothing particularly innovative, envelope-pushing or scandalous about Dawe’s novel. It is very much a mainstream book. In the 1990s, there appeared in American young adult literature a phenomenon that came to be called ‘bleak books’; books, that is, which addressed, the then darker realities of quotidian teenage life with a candor that some – myself included – found refreshing, others, scandalous.

In the context of contemporary American young adult fiction, there is nothing particularly innovative, envelope-pushing or scandalous about Dawe’s novel.

These books boldly addressed such hard-edged topics as paedophilia, insanity, murder, suicide, rape, juvenile incarceration, serial slaying and a grim catalogue of others. This excited, at the time, a certain degree of controversy in professional librarian ranks, a controversy that the mainstream media picked up on and sensationalised. The hub-bub subsided fairly quickly, however, and YA became a considerably more sophisticated and mature body of literature, which now has, if you will, carte blanche to explore the realities of teen life, no matter how dark, provided the exploration arises organically from character and situation and is not imposed on the narrative or, worse, is gratuitous, catering to prurient interest or sensationalism. If it happens in the real world, why should it not ‘happen’ in the pages of a novel?

Which brings us to Dawe’s book. Yes, it is not perfect. For example, it has justifiably been criticised here for its one-dimensional treatment and objectification of girls who seem to exist only as vehicles for Devon’s coming of age sexual experiences. Its serviceable style is often far from artful, although it succeeds in communicating its content and, perhaps especially, the emotional realities of its characters’ lives. I gather the original book was much longer and it shows in what must have been significant edits, which leave a highly episodic structure and incidents of what I might call ‘truncations’.

These reservations aside, Into the River compares favorably with American coming-of-age-as-outsider fiction. Indeed, I would go so far as to say it is exemplary in that regard. For Dawe does a superior job of limning Devon’s growing estrangement from his native environment, coupled with his sometimes precarious efforts to fit into his new world. One aspect of that environment that, I presume, added to its controversial nature is the presence of the gay teacher, Mr Willis, the arguable homosexuality of Steph, and the relationship the two apparently have. A relationship that I, as a gay writer myself, deplore while at the same time acknowledging its sad existence in the real world.

… Dawe does a superior job of limning Devon’s growing estrangement from his native environment, coupled with his sometimes precarious efforts to fit into his new world.

Literarily, it is equally realistic, especially as it enriches Dawe’s characterization of the cynical Steph, who – next to Devon – is the most fully realised character in the book. I don’t for a minute, however, accept Steph’s notion that Devon is himself ‘bent’. His same-sex physical encounters – and his attitude toward them – establish, to my mind, his heterosexual bona fides. As for setting, the world of private schools is an increasingly familiar one in American young adult fiction and Dawe’s take is commensurate with ours on the subject. Finally, the book is particularly successful, I think, in depicting Devon’s growing desire to be free, as evidenced in his attachment to his ancestor Diego Santos and in his memorable, book-ending cry of ‘Libertad.’

Michael Cart

Michael Cart, a columnist and reviewer for the American Library Association’s Booklist magazine, is a leading expert in the field of young adult literature. The author or editor of 23 baooks including his critical history of young adult literatureFrom Romance to Realismand the coming-of-age novelMy Father’s Scar, an ALA Best Book for Young Adults, he is a past president of both the Young Adult Library Services Association and the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents of the National Council of Teachers of English. He is the 2000 recipient of the Grolier Foundation Award and the first recipient of the YALSA/Greenwood Press Distinguished Service Award. He lives in Columbus, Indiana.