Kyle Mewburn tells us why our children’s writers are so special, and opens a discussion about why New Zealand should appoint a Children’s Laureate.

If your orbit has intersected with the local children’s literature scene over the last few years, you’ve likely heard mutterings about our need for a Children’s Laureate. (Or have I just been hanging round the wrong bars?) The role of a Laureate would necessarily be broad – ranging across the vast terrain of children’s literature from readers/reading to writers/writing; and flexible – catering to each Laureate’s specific interests and strengths. A Laureate would be an ambassador, advocate and standard-bearer.

A Laureate would be an ambassador, advocate and standard-bearer.

Inspired, in part, by the success of the Children’s Laureate programme across the ditch, an informal working group recently got together to formulate a draft plan of attack.

While there is much guidance and encouragement to be found in existing Laureate programmes from the United Kingdom to Australia, Finland to Mexico, Holland, Sweden and Wales, it is essential any Laureate programme is tailored to suit the local literary landscape. Undoubtedly the biggest hurdle is that creative arts bugbear – money/sponsorship. But children’s writers are generally optimistic souls, so let’s not dwell on the hows and whens. Instead, let’s consider the deeper question of why, and what it is a Laureate does.

Each Laureate programme has its unique set of goals. Personally, I like the overarching theme of Ireland’s Laureate na nÓg – to engage young people with high quality literature and to underline the importance of children’s literature in our cultural and imaginative life. I suspect similar arguments were made in support of the first Te Mata Poet Laureate in 1997.

Every good cause needs an advocate.

Every good cause needs an advocate. An ambassador. And could there be any better, more essential or timely cause than encouraging kids to embrace indigenous literature so they might grow up to be not only literate adults, but thinking, caring, passionate, compassionate human beings and proud citizens of New Zealand?

The goal of a Children’s Laureate is to do for NZ literature what self-appointed good food ambassador Jamie Oliver has done for healthy eating. That is, promote the value of consuming wholesome, nutritious local product over imported (mostly), empty-caloried junk.

Raising the profile and value of children’s literature

An equally important, yet sometimes overlooked, ingredient in the equation is the Laureate’s role as an advocate for local literature, writers and illustrators. If I may again defer to the Irish scheme, a Laureate would be tasked with ‘raising the profile of children’s literature and bringing (it) into the mainstream conversation about books and literature.’

For me, education is the key. Far too many people, readers and writers alike, consider the task of writing for kids a lesser pursuit requiring little craft or thought. How many times have I been reliably informed that ‘all you need to do is add some bums and farts. Kids love that stuff.’ If only it were that easy.

Of course, it might be argued that any writer can write a children’s story. This is technically correct. It is neither especially difficult nor particularly onerous… technically. Indeed, even Salman Rushdie has written for children. But there is a fundamental flaw in this kind of thinking. Equating ‘writing for children’ with ‘writing stories children love’ overlooks the specialist talents required to write successfully for children. A children’s writer must, firstly, possess the ability to not only view the world from a child-friendly perspective, but also portray this in an accessible, inspiring and entertaining way.

There is a yawning gap – quite literally – between writing a book children can read, and writing a book children enjoy.

There is a yawning gap – quite literally – between writing a book children can read, and writing a book children enjoy. For me, the crucial distinction between the craft of writing a story for adults and the art of writing for kids can be summed up in four words – we are not children.

This simple reality makes writing successfully for children eminently more challenging than writing for adults. While adult writers may write for themselves – or versions of themselves – children’s writers are afforded no such luxury. The intended reader must always be at the forefront of our thoughts. The moment we indulge ourselves, we risk losing our readers’ interest. And a young reader’s interest, once lost, is unlikely to return. Most young readers are, understandably, unwilling to struggle through a tome simply because they liked the author’s last book. Younger readers have no loyalty. Indeed, most are unaware of the author’s part in the creation of their favourite stories.

A conjuring act

Therein lies the magic of children’s literature. And I use the word ‘magic’ not as hyperbole, but because there is simply no other word that adequately describes the conjuring act required when writing stories for children. It is alchemy of the highest order. Instinctive and intuitive.

It is little wonder so many find this a difficult concept to grasp.

Such an undervaluing of the specialist nature of children’s writing inevitably leads to a diminishing of respect, minimal investment and, more importantly, a dearth of public debate, discussion and celebration. This is, I believe, to the long-term detriment of everyone – readers, writers and society alike. It is this debate a Children’s Laureate would inspire.

Literacy is the cornerstone of a decent, caring society. It has been widely demonstrated that reading fiction fosters empathy. Literature reflects and directs our national identity. It is both mirror and map. Carrot and stick. Having a strong, diverse literary scene unique to New Zealand is vital for the country’s well-being. And I would argue having a strong, diverse, respected and valued children’s literature scene is vital for the well-being of New Zealand literature.

Having a strong, diverse literary scene unique to New Zealand is vital for the country’s well-being.

Overcoming the cultural cringe which often surrounds indigenous literature is not a short-term project. Readers of local literature must be grown. And the best place to start is when they are just beginning their reading journey. Growing an affection for, and loyalty to, New Zealand stories requires their reading path be paved with quality local stories. Stories which reflect their own lives.

Though some might argue a Children’s Laureate is merely a symbolic gesture, what a powerful symbol it would be. Not only for local creators, but for the nation’s young readers.

Of course it is not a solution. Nor is it some idle fancy or extravagance. It is simply an essential component of any healthy, vibrant literary landscape. Its absence in New Zealand should be cause for some concern.

It is time something was done about it.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

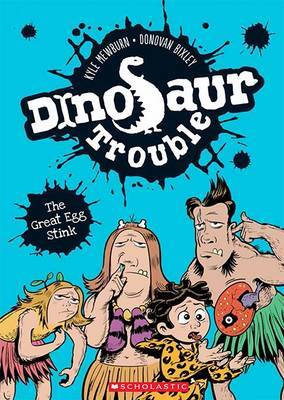

The Great Egg Stink (Dinosaur Trouble #1)

By Kyle Mewburn

Illustrated by Donovan Bixley

Published by Scholastic NZ

RRP $5.99

Kyle Mewburn

Kyle Mewburn is one of New Zealand's most eclectic and prolific writers. From multi-layered picture books and laugh-out-loud junior fiction series; to short stories, novels and memoir; her titles have been translated into eighteen languages and won numerous awards including Children's Book of the Year. She was Children's Writer in Residence at Otago University in 2011 and President of NZSA from 2013–2017. Her most recent novel, Sewing Moonlight, is published by Bateman.